Nineteen-Seventy-Seven

I

I felt awed by the great ten-year retrospective in the Dalhousie art gallery in 1977. It was like going through an exhibition by someone else. Even paintings that I’d seen a number of times at home—seen up on the studio wall being worked on, or hanging up in the house—became unfamiliar in that context.

There were so many works there, so much variety, such individuation, such richness, such energy, such plenitude. I had the feeling of creative energies now at last in full flood.

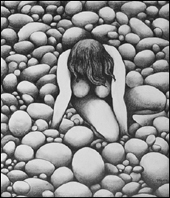

The drawings, especially, made me feel that since some of the finest—the woman in the deck-chair among waves, the woman kneeling among stones, her breast stone-shaped—had been done for the show, done fast and seemingly effortlessly, it was as if she now had a vocabulary that could go on being developed

Those drawings, the iconography in them, were new and hinted at much more to come. I’m sure that had there been another three or four weeks, more would indeed have come.

II

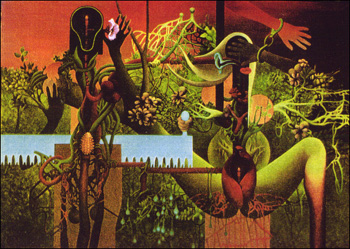

There was such playfulness too in some of the works.

You had the obviously major and sometimes painful and disturbing oils, such as the Grandparents and Couples pairs, and Headwound, and the painting of the obviously rage/desperation-filled six-armed woman that, with the bit in Huckleberry Finn where Huck says that a woman in a drawing looked kind of spidery, I had dubbed the Spider Lady.

But there was also the sheer joy in image-making in a number of the small oils, in which metamorphoses went on and analogies were perceived—the foot that was a ridge of hills, the hands that were also birds.

And there was play too, and a fearless willingness to be a bit childlike, in the large oil of the opened heart among trees, with small creatures and birds, among them her beloved owls, nesting in and around it.

Everything was being transformed inside the theatre of the mind.

III

It was a magisterial exhibition, a great exhibition, a profoundly enriching one. It was marvellously hung by Mary MacLachlan (working closely with Carol) who curated it and wrote the admirable long essay on her in the catalogue. It was an exhibition that needed to be experienced in its full three-dimensionality, which one couldn’t get from the catalogue.

IV

But the momentum was broken. I am quite sure that had there been a recognition of the show’s—and C.’s—distinction across the country, she would have worked with even more energy and confidence.

The show traveled, though not, I think, in its completeness. It was hung at the Beaverbrook, at the Newfoundland gallery, at the McLaughlin in Ontario, at the Burnaby, at two or three other places, and the Halifax artist Felicity Redgrave praised it generously and knowledgeably in a long review in ArtMagazine.

But the writer of the brief review in ArtsCanada obviously preferred her earlier work, and we waited in vain for newspaper reviews from Ontario and elsewhere that might have drawn people in to see it.

The CBC radio review by a Halifax artist was so unrelievedly hostile that two or three of us—Malcolm Ross, myself, maybe someone else—wrote to the CBC protesting about it. The review had gone out across the country before the show traveled.

Our local paper gave the show four lines.

V

In 1977, too, a local but, in its implications, much more than merely local ideological art-struggle heated up.

She did no painting for the next two years, and from then on she became the Invisible Woman of Canadian art, without even the consolations that fueled the dreams of the original Invisible Man.

The Couple, 1973–76, oil