Giorgione, The Tempest, ca 1505

Art

I

When I told someone who didn’t know much about art that my wife had been an artist, he asked (obviously expecting the answer yes) whether she had liked Picasso. I felt a bit embarrassed at having to say that, no, she didn’t especially like Picasso. A modern artist who didn’t especially like Picasso sounded to my ears rather suspect; and I couldn’t immediately bring to mind the names of modern artist whom she had in fact liked and whom I felt he would recognize.

When I first met her, I may have asked her the same question

I knew that she liked Kollwitz because of the unstretched, larger-than-life-size painting of a woman’s head, brown against a green background, that was tacked on the wall of her studio, and that had the kind of maternal tenderness that I associated with Kollwitz.

But after that?

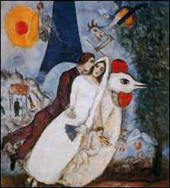

I’m pretty sure that the configuration of names that slowly emerged—and I’m sure it was slowly—sounded odd to me: names like Beckmann, Soutine, Rouault, Chagall, Nolde, Kollwitz, Barlach, Marin, Ryder, Kokoshka, Munch.

She wrote her MFA thesis on figure painting in Chagall, Rouault, Soutine, and De Kooning. I shall talk about it elsewhere in these jottings. It was a brilliant piece of work.

Oddly, I can recall few other names from those Minneapolis years. Her friend and fellow MFA student Bill Bartsch was writing his own thesis on Francis Bacon, who mattered a lot to me too. So Bacon was some kind of presence, and later we went to the great Bacon retrospective at the Tate in 1962.

I remember her being angry when the technically brilliant and emotionally arid sculptor teacher in the Minnesota art department dismissed Rodin as simply “reticulated surfaces,” or some such term. I remember our going to a Lipschitz exhibition at the Walker. She was respectful towards Lipschitz.

I had better let earlier artists in.

II

On our first trip to Europe in 1957, we went from London to Oslo to Gôttingen to Dubrovnik to Venice to Paris.

In Oslo we were in the National Gallery, and there must have been some Munchs there. I can remember our going through one of the large galleries in Venice and finally becoming enthusiastic in front of Giorgione’s Il Tempesta—so small, so mysterious, so magical, and so much weightier than the vast dark paintings of sea battles and the like.

I recall very little of our gallery-going in Paris. We went to the Louvre, I know, and admired Rembrandt’s Bathsheba naked with a letter in her hand. We probably agreed that Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe looked artificial. We must also have gone to the Orangérie, unless it was closed for repairs or whatever.

I imagine that I took her to what was for me the Paris bookstore, the Surrealist Le Minotaure. And yet, and yet, that too may have been closed for August, which I imagine is when we were there. I don’t recall our buying any art books, except maybe one on Manzú.

III

My memory of that trip is far more of places, so I suspect that art per se did not figure much for us.

I remember the sea voyage from Quebec City to Southampton on one of the Cunard ships, the Sylvania perhaps. We revelled in the abundance of food and the cheapness of drinks; walked the decks; tried to play chess and had the board turned the wrong way, as a puzzled spectator pointed out after a few minutes (C. liked telling that story.) ; were appalled by the spectacle of redneck Canadians in plaid shirts drinking Red Eye, a mixture of beer and tomato juice (delicious actually).

In London we stayed at Finchley, North London, in what had been the family house since 1936 or so. I remember my father taking us on one or two Sunday visits to country houses in his car. I’m sure that C. and I went to the Zoo, which we revisited each time we were in England. I took her to Oxford, I’m sure, and showed her, among other things, Balliol, Magdalen, and the charming Botanical Gardens.

IV

We also spent three hours in Cambridge with my hero F.R. Leavis on the Downing lawn. I had written to him from Minneapolis as an admirer, and an exchange of postcards had finally gotten us together. Mrs Leavis was in hospital at that time (he pointed to the distant window of her room), and was in no hurry to go anywhere. I should have made notes afterwards. All I have now are a handful of fragments.

He was amused when I mentioned meeting a gentlemanly Scottish-born English professor in Florida a few years before who had known him in the Twenties and recalled Leavis’s vaulting over a five-bar gate on one of their walks together. (“No, he wasn’t the athletic type, was William Constable.”)

I asked him about the Great War. He spoke of the guns lined up wheel to wheel and laying down their interminable appalling barrages. No, he hadn’t carried his pocket Milton all the time with him in the trenches, as an article of his implied, but one had to use all the moral weapons one could against his more “traditional” colleague E.M.W. Tillyard.

I asked him if it was true that he was of Huguenot stock. Oh no, his family had been Quakers. He himself was a phlegmatic Englishman, he said. His wife was the temperamental one in the family. He spoke of T.S. Eliot sneaking through the back streets of Cambridge to visit him, and sitting on the edge of the table, and smoking cigarette after cigarette, and looking terrible. (“He’s not a nice man, is Tom Eliot.”)

He spoke of Tillyard trying to persuade him to take a chair at the University of Johannesburg. “‘He said, ‘I hear it’s quite a centre of culture these days.’ I said, ‘Tillyard, I know about Johannesburg. I have read about Johannesburg.’”

He spoke dismissively of the American critical journals. I said that at least they occasionally carried articles by Yvor Winters. He said, dubiously, something about, “Well, perhaps on fiction.” He referred to his son Ralph as a genius.

V

I remember the rough sea crossing to Oslo, the long stemmed flowers in a vase that drooped and soared with the ship’s movements, the barman who finally got annoyed because we weren’t entitled to use the first-class bar. (Such things didn’t bother C.) I remember the delicious fresh-boiled shrimp that we bought in paper bags from one of the shrimp boats moored against the quai in downtown Oslo.

I remember the comfortable large family house on an island in a fiord down the coast, where Captain and Mrs Waage were visiting with his widower twin brother. The other Captain Waage and his three boys obviously had little time for Madame Waage, who preferred Haifa and her native Brussels to Norway, and no doubt made it clear. It wasn’t a restful time, but the fiord was beautiful.

I think C. he had been in Norway during her first European trip in the early Fifties.

VI

I remember our night in Hamburg when, at my desperate insistence after she recalled having been taken to a street in which there were clubs in which naked women walked around, she got us out by taxi to the Pauli district, the notorious but not sinister-feeling Reeperbahn.

I remember our time, a week or two, in Gottingen, where we stayed at the Nansen House, a large house near the outskirts which during the war had housed some of the SS. Afterwards, a “good” German with a vision of international brotherhood had turned it into a hostel-cum-social centre where student visitors from other countries could stay for a pittance and mingle with idealistic young German students.

Our friend Rainer Friedrich, who turned up like an angel on my doorstep late at night some weeks ago just when I was reflecting that there was no-one around with whom I could really talk about C., had been there himself a bit later and spoke of it with amused affection as a hotbed of what later became SDS students.

That was probably the single most important—creatively important—year in C.’s life.

They ate lots of potatoes, enough for her to return to the States weighing over 160 pounds; talked a lot; had a lot of innocent fun together, putting on student performances and the like. I think she must have been very animated and very popular—very different, certainly, from the German image of American girls.

Her German must have been fairly good by the end of her time there. It was the kind of atmosphere in which people didn’t have to worry about making mistakes. I think she must have got a fair amount out of those theological lectures that she attended at the University. She spoke of the beautiful German of one of the eminent theologians. She recalled the fervour with which he asked, “Was ist Geist? Geist ist....”

Once or twice she went on hitchhiking excursions with what she referred to as “my friend Alan, “ a cheerful Scotsman who wore a kilt. She recalled one or two scarily high-speed rides on the autobahnen.

When we were there there was no-one, I think, who remembered her, apart from the Director and her former German teacher, a woman.

One night, when we were out walking, we came upon an obviously disturbed hedghog that was making its way to nowhere along the sidewalk beside the wall of a public gardens from which it must have wandered. We restored it to where it belonged. Neither of us had ever seen a hedgehog before, nor ever expected to. C. always remembered that incident.

We also remembered the kindness of a complete stranger in a sausage-and-beer eaterie who took us to be penniless students and had two portions of beer and sausages sent over to where we were trying to figure out the menu.

VII

I remember our climbing the tower in the castle at Nuremberg, and peering into the enormously deep castle well, and visiting Durer’s house. I myself also wanted to visit the medieval torture chamber in one of the towers on the city wall that I had heard and read about before the war. When she enquired, people looked at her as if she were saying something indecent. Apparently the tower had been destroyed by Allied bombing, and a good thing too. Finally someone told her that there was one in Regensberg.

I remember the train ride near dusk that felt as if it were taking us deeper and deeper into the Black Forest, and the fourteenth-century hotel with low ceilings and narrow twisting corridors where we stayed the night, and the odd atmosphere of unfriendliness in one of the beer places that we went to (I read later that around that time there had been a sex scandal involving children), and the man who pointed with furtive pleasure to where a synagogue had been burned down with the Jews inside it.

VIII

I remember Belgrade, where I had violent food poisoning and we had to spend three or four days in our room in the furniture-crammed apartment of a gracious bourgeoise who spoke no English or German, and C. having to buy medicine for me and try to convey to the pharmacists what afflicted me. (She was pleased when she found that the term was “Durchfal.”)

I remember Sarajevo, where we liked the Turkish-feeling atmosphere in certain areas (mosques, men in baggy pants, carpets, coffee brewed in small copper pots, and so on, and were impressed by the massive evening promenading of people along one of the wide streets, and were even more impressed when one of the promenaders turned out to be someone who knew C., and where we went to a Bing Crosby/Bob Hope movie, probably My Favourite Brunette.

I remember the perfectly preserved walled city of Dubrovnik (we were there because we had seen a travelogue about it back in Minneapolis), and the strutting jackbooted Army officer who imperiously demanded the film from my camera when he thought I had photographed a seaplane in the harbour in the suburb where we were staying, and whom I managed, by dint of voice inflection and body English, to persuade him that I was innocent.

On the boat from Dubrovnik to Venice, we—or rather C., for they spoke only German—got into conversation with a group of Russians, I think because one of them had enquired about C.’s Argus camera, which I had appropriated. Apparently he didn’t think much of it, or of me, when he found out one or two details about it, but he and the others obviously enjoyed talking with C.

I remember our coming into Venice at night, and the winding streets through which I, at least, managed to find my way, and the French-feeling cheap clean restaurant where we ate several times, and the glass-factory into which we peered, and the pigeons in St. Mark’s piazza. C. had been to Venice before, during her European winter, and spoke of its having been bitterly cold and damp. We did not ride in a gondola. They were much too expensive for us.

IX

I remember the feeling of relaxation and renewed well-being I felt when we reached Paris after all this alienness—my city, my language, my querencia. We may not have had long in Paris, and we did the usual tourist things—visited Notre Dame, visited the Sainte Chapelle, whose stained glass windows she adored, visited the Flea Market, which she liked a lot, went up to the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre, walked around the Place Pigalle.

Coming down the Butte Montmartre on our way to Pigalle, we wandered slightly off the beaten track, and ended up having supper in a hidden-away family-type restaurant with pink lampshades, where the proprietress and her clients engaged in loud genial dialogues with each other. The dish of the day was couscous, of whose existence we were completely ignorant. The proprietress put a large tureen of the grain-and-soup part on our table, and showed us how to mix in the other ingredients. Everything was delicious.

She and some of the other diners obviously looked benignly on us. We were young, it was perhaps obvious that we weren’t long married, and I suspect that very few tourists normally ended up there. At one point a porcelain ashtray shaped like a scrotum and penis circulated among the diners, to the accompaniment of laughter and humorous, no doubt coarse, comments. C. loved the experience of that place, and spoke of it on various occasions afterwards.

X

I have only now realized that that trip, which C. obviously cared a lot about, was for her our honeymoon trip.

She made it possible by teaching three different classes during the school year, one of them a nightschool language class in St Paul for immigrants who wanted to become American citizens. She was teaching that class when I met her, and she obviously took a very personal interest in the mostly middle-aged students.

I think she did fairly little drawing on the trip, though she took along a sketch book. The drawing of an elephant in the London Zoo may have been done then.

XI

There was a lot more art during our second trip, in 1962.

In London, as I said earlier, we went to the great Bacon show at the Tate, and to an outdoor exhibition of sculpture in Kensington.

In Holland, where we visited a couple of friends, Seymour and Sarah Betsky, we went to the Staadtlich in Amsterdam, revelled in the Van Goghs, sneered at the Lichtensteins and other examples of American Pop in a nearby room (“Look first upon this picture and then on this”) We also took a bus, or was it a cab?, out to the Kroller-Mueller Museum where the other Van Goghs were. In the Rijksmuseum we were especially turned-on in the great Rembrandt room. I’m pretty sure that The Jewish Bride was for C. one of the highest points that painting had reached.

In Brussels we visited the Waages and slept—a taxi driver having taken us there—in a hotel in the red-light district near the station that, to judge from the number of mirrors in the room, the red-shaded lights, and the general overripeness, served the ladies of the night.

In the Musée des Beaux Arts we were thrilled—it isn’t too strong a word—by the Memling portraits, postcards of which we put up on the wall above our kitchen table, and by the Brueghels, especially the incomparable, nacreous Fall of Icarus, a large reproduction of which I had taken to Israel with me. Brueghel was for C., in those years, one of the painters, along with Bosch, and she was delighted and moved when our friend Jim Clark gave her his magnificent, near-complete book of reproductions of Brueghel’s paintings.

In general, she was especially drawn to the Medieval and early Renaissance rooms in museums.

XII

We did a fair amount of gallery-going together over the years. I shall now jot down memories simply as they come.

There was a large show of César at, I think, the Staadtlich, maybe in l964. She liked that; felt he was genuine, crushed cars and all. On the way to it we passed between a number of Apels, which she also respected.

Another time, in the Seventies, there was an outdoor exhibition of Henry Moore, probably at the Jeux de Paume. She liked Moore a lot. He was probably her favourite modern sculptor. In 1964, at least I think it was then, we went to the massive show of current modernist works at the Tate. It was oppressive, and she hated the experience.

In the early Eighties we made a special trip to Washington to see the Munch show at the National Gallery. Munch spoke to her very intimately, even in what are generally thought of as the weaker paintings done after his breakdown in 1910 or thereabouts. I remember her praising a painting of logs being hauled through a snowy forest. I know that she was moved by the self-portrait of the artist during one of his insomniac nights—thin, lonely, staring.

Unfortunately I didn’t accompany her on the trip she made to New York to see the great Bonnard show at the MOMA. I think I felt vaguely obliged to stay in Halifax, but I could have gone had I really wanted to. I regretted my mistake all the more when she reported going through the great Hopper show at the then nearby Whitney. Bonnard, too, was one of the artists for her. She respected Hopper but never cared much for him. A few years later I made a trip alone to Washington to see a smaller but still marvellous Bonnard show at, I think, the Clark or the Corcoran—at any rate, the smallish museum somewhat away from the centre of the city. We had gone to that museum together earlier.

A particular thrill on another occasion, when we were visiting our friends Herschel and Jane Shohan, was the Clark museum at Williams, all the more thrilling because entirely unexpected, with its large marvellous Winslow Homers and its glowing Impressionists, in an ideal, architecturally unfussy building not cluttered up inside by displays of the show-maker’s art.

Did we go together to the Monet exhibition at the Met? I’m embarrassed not to remember.

At least I know that we went together to the Courtauld gallery in London, more than once, and particularly lingered over a small, rocky northern landscape, perhaps by Brueghel. And that we visited large retrospectives of Miró (she particularly liked the late ones) and the three Duchamp/Villon brothers at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris while it was still over at the Palais Chaillot. Duchamp didn’t interest her much. Later we went to the Beaubourg together, which she detested.

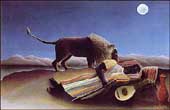

I especially remember our going to the large Ernst show at the Petit, or was it the Grand Palais? The crowds made viewing difficult, especially of the collages, which fascinated her, but I suspect that the show stood alongside the Bonnard and Munch ones as one of the high points of her exhibition going. I remember, too, our standing together in front of the Rousseaus and the Manet flower paintings in the Orangerie.

I cannot recall when the Surrealists started being a strong presence for her. It was Ernst and Magritte above all who mattered, though she always spoke respectfully of Dali ‘s earlier works. We were charmed when we spent a night in a small Brussels hotel with a huge mirror confronting you at the end of the narrow hallway, and felt that we were inside a Magritte, or at least inside Magritte’s world.

Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride, 1665