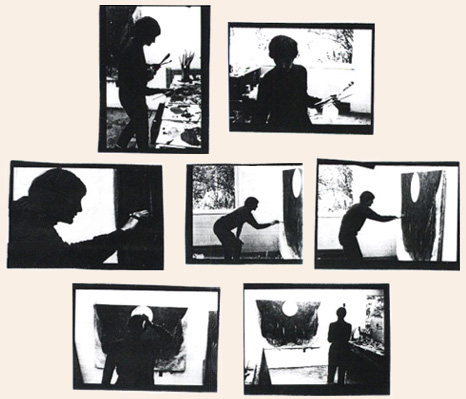

Photo Robert Eugene Wilcox, 1963.

I

Carol Hoorn Fraser was born in Superior, Wisconsin, in 1930, and grew up there, but the Hoorn side of the family were Minnesotans.

Her Swedish-American father, a Lutheran pastor who built two of his six churches and taught his two young daughters the use of edged tools, had helped put himself through Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota with cartooning and embroidery.

Her mother (no, not of Swedish stock; more English-American than anything) had an M.A. in Home Economics, was an expert seamstress for the family, and did charming pastels before her marriage. In later years Carol’s sister Milly, who had graduated earlier from Gustavus, worked with stained glass and collage.

Superior, the poor twin of Duluth on Lake Superior (like Saint Paul-Minneapolis and Dartmouth-Halifax) was a mixed environment, part industrial, part quasi-maritime (this was one of the great lakes, with ore boats on it), part rural at its edges. And during the Depression years, depressed.

Arvid Hoorn’s income during those years was minimal (sometimes he might be paid in produce at his four rural parishes), and when he died of cancer in 1946, the family was left virtually penniless, apart from the family home that he had built beside his church in Superior. Hazel Hoorn had to go back to work as a Home Economics high-school teacher, and Carol completed the last two years of high school in a single year.

II

She graduated from Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota in 1951 with a major in chemistry and biology and a minor in art and literature, worked for a couple of years as a research chemist at Archer Daniels Midland (a major grain company in St. Paul), saved $600 from her salary, and went to Europe for a year, spending most of the time in Göttingen.

There she attended theology lectures at the University and, in Nansen International House, where she boarded, met a number of young Germans whom she later called the most impressive group of people she ever knew. I have been told that some of the later leaders of Students for a Democratic Society were associated with Nansen House.

Back in Minneapolis, she worked as a nurse’s aide in a surgical recovery ward at the University Hospital, did art therapy with mental patients, and picked up enough extension-class credits to be accepted into the University’s Master of Fine Arts programme, from which she graduated in 1959.

By then she was one of the brightest lights among the younger Minnesota artists, taking top prizes at juried shows at the Walker Art Center and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and having a number of her works bought by local institutions, the Walker among them.

III

She and John Fraser, who was doing a Ph.D. in English at the university, met and married in 1956. In 1961 they moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia, when he was offered a job at Dalhousie University. They lived in Halifax for the rest of her life, apart from a couple of summers in Provence and three sabbatical residences in Mexico.

In the Sixties, while Doug Shadbolt was the Director, she taught drawing part-time in the School of Architecture at the Technical University of Nova Scotia.

Near the end of the Seventies she was Acting Director of the Dalhousie University Art Gallery for a year, curated a major show of Expressionist prints, and began her free-lance public lecturing..

She was also very active in a fight to preserve the famous Halifax Public Gardens from the visual encroachement of a highrise development.

In the Eighties, thanks to Joe Sherman’s helming of ArtsAtlantic, she did some incisive, generous-spirited, and at times mordantly funny art-reviewing.

She died at home, of cancer of the lungs, in April 1991.

IV

Her realist/expressionist landscapes in the Sixties were very popular, as were (locally) her magnificent series of watercolours in the Eighties.

But the works during her astonishing decade of creativity from 1967 to 1977 aroused mixed feelings, and from then on, for reasons partly art-political, partly health-related, she became, outside the Atlantic Provinces, pretty much the Invisible Woman of Canadian art, without even the questionable benefits of invisibility that fueled the dreams of the original Invisible Man.

But she went on making lovely, vibrant, unintimidated art until the end.

V

The fullest site for texts by and about her is the one for Thistle Dance Publications. The obituary by her friend the curator and art-historian Gemey Kelly is especially fine.

Thistle Dance (in which I should maybe say I am not a partner) exists because of the vision and pertinacity of our friends Joyce Stevenson and Joyce’s husband Rob. Thanks to them, high-quality reproductions of forty of her Eighties watercolours now have hard-copy being.

I have also been delighted by the early oils on Carol Geary’s California site Carol Hoorn Fraser in Minnesota.

VI

Is it possible, in this age of information, when everyone is sure that he or she would not have made the mistakes that were made with artists like Van Gogh, for a marvellous artist to be off the official map?

Could Van Gogh paint?

Those lovely writers Jean Rhys and Zora Neale Hurston became invisible for years. It does happen, you know.

Fortunately, thanks to the Web, better cartography is now possible.

Carol’s friend the art-historian and curator Mimi Cazort said after her death that she belonged with Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keefe. But probably by now there are a number of nominees for that position.

She was herself. She was Carol Hoorn Fraser.

Enjoy her.