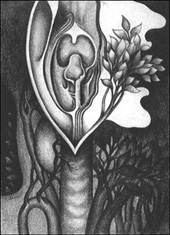

Major Surgery, 1969–77, oil

Body

I

She had migraines, essentially food related, which largely disappeared once the cause was discovered, thanks to the Halifax allergist Leah Nomm. She virtually never talked about them while they were going on—didn’t go into details about what she was feeling, didn’t make pain gestures (grimacing, massaging her temples) that would invite sympathetic questions. Probably she didn’t want to become a bore. And no help was possible anyway. Occasionally she’d refer later to the migraine that she had on this or that occasion.

She suffered for awhile from chronic sinus infections, which finally improved somewhat after surgery that permitted drainage, but which left her cheek numb for a good while, and which she sometimes regretted.

There was some arthritis. She had a painful, at times I think very painful, left-knee. She had some attacks of cystitis, an especially savage one when we were in Majorca with the Bobaks in the summer of 1967.

Her eyes became light-sensitive. She hated the hard winter sun at breakfast, especially when reflected off snow. She would sit in the shadow of a curtain, or with dark glasses on. She did not wear those glasses for cosmetic reasons.

The aches and pains tended to rotate, one taking over when another ceased—headaches, stomach troubles, constipation, sinus, arthritis, etc. We’d joke a bit grimly about how this one had had its turn, and now another should be given a chance.

But the pattern made things problematic for doctors, and though we were very lucky in our two family physicians over the years, William Pollett and Kingsley Gill, I know that there were difficulties at times with specialists who got impatient when they couldn’t clear something up. I’m sure she must have heard the word “psychiatrist” more than once.

II

She had some ferocious hangovers in the Sixties after drinking brandy. She simply wasn’t willing to give up and be a party-pooper, spoil those leisurely, gossipy, joke-telling sessions around the table with friends like the Bobaks.

She was allergic, as it emerged, to alcohol, dairy products, eggs, corn, spores, moulds, perfumes, cat hair, wool, car-polluted air, insecticides. She was allergic to the lovely-scented tropical flowers that bloomed outside her window in Tepoztlán. That was in the summer of 1982, our second sabbatical. She was unaware at the time about eggs, corn, and dairy products. We ate a lot of them in Mexico. At least she wasn’t allergic to beans.

On the day when we had to get from Tepoztlán to Vera Cruz, a long hard drive, she was hit by a stomach pain so severe that I had to drive for six or seven hours straight, until I simply gave out, whereupon she took over as darkness fell and drove us confidently into the unfamiliar city. Her body, faced with a crisis, must have kicked in with a fresh supply of adrenalin. An acquaintance had made us one of those greasy, fancy, you’ll-simply-love-this dishes for supper the night before.

She bought the food-allergy books of Adele Davis, and did research in the Dalhousie medical library. Doctor Gill liked and respected her and she him (he had done medical missionary work in India), and in the end she was able to get a regimen of medications that worked. There were five or six of them, what with taking care of side-effects. The carrying bag that she took down to Mexico in 1989 was heavy with them.

III

Asthma, asthma, asthma. One dreadful attack when she and her sister Milly down near Boston went through an old family trunk put her into hospital, and the adrenalin they pumped into her kept her sleepless for thirty hours straight with a tube down her throat. Around Christmas in 1982 another attack almost closed up her air passages altogether, and I drove her to the Victoria General Hospital, and she was in Emergency for two or three days with a machine doing her breathing for her, and double pneumonia, and more recovery time after that. A week altogether, I think.

Her lungs had been damaged by the formaldahyde from the foam insulation that we’d had injected into our outside walls in 1977 (the government was urging it), and which we had expensively removed in the winter of 1982-83. My own eyes when I was in my work corner in the living room would have that slightly teary feeling that you get in a dry-cleaners. The beastly stuff was there.

Her rib-cage was a good deal enlarged because of the asthma.

She had quit smoking in the early Seventies, after a dreadful struggle.

IV

It was a grief for her, having to shut our beloved cats out of the bedroom.

It also became harder for us to go on interesting walks together.

She had enjoyed going out to the Birch Cove Lake in the Sixties. It was a lovely lake. You drove ten or fifteen minutes to a spot on the Bicentennial Highway, parked, and then walked through the woods for ten minutes along what had once been an unpaved road along which quarried stone had been hauled. The shoreline of the lake curved and twisted intricately, and you could get to the water by two or three different routes. You could also walk and clamber along the water’s edge for a comfortable distance. There were usually only a handful of other people out there—sometimes no-one. Not a sign of civilization as you lay on the glacier-rounded granite rocks and looked at the blue sky. Like a beer commercial.

When we went out there again in the Seventies on one occasion, I had to figure out which route would be least taxing for her and least twist her body, and we went slowly. After that I went on my own, except when we took Bruno and Molly Bobak out there once.

So that was one kind of walking that she lost—rough walking, exploratory walking, risk-taking walking, with the two of us discovering things together, or me discovering something and then taking her there later so that she could share it. And it was indeed risk-taking at times. I recall the two of us in the Sixties making our way from rock to rock along the cluttered and jumbled shoreline of one of the small bays on the lake. It would have been easy enough to misstep and twist an ankle or break a leg or crack a rib, but she was sure-footed and fearless.

V

When things were absolutely at their worst, it was hard for her to walk the short and slightly uphill couple of blocks to our corner grocery store, and harder still to go another block to the Dalhousie Arts Centre. She would say, with a slight edge of irritation on her voice, “I’ll be all right if you don’t make me hurry.”

Later things got better, with better medication. In Ajijic in 1989 we had a very nice two-mile walk one day past the cemetery and out beyond the edge of the village, and then back along the shoreline of the lake, Lake Chapala. But there was no way in which she could have climbed up to the small shrine in the hills behind the village.

VI

These problems were all the more ironical because of how strong and vigorous she used to be.

As a kid, she was allowed to run very free in the area around her home—swimming in Lake Superior until she was blue with cold; skating; roaming the woods and fields with a pack of other kids, two or three of whom ended up in reform school.

She had been a powerful swimmer, with what she said were a swimmer’s shoulders—broader than mine, certainly. I recall her speaking in passing of some very high dive that she had made—forty or fifty feet?—from a bridge

VII

During our first winter in Halifax, we acquired our first cat, Alfie, a half-grown tabby stray that she found quivering with cold on the steps of our apartment building. We decided after a few weeks that he needed a scratching post, and went out on a bitterly cold Sunday afternoon to look for one on the waterfront at our end of the peninsula. We must have been crazy, for we settled on a waterlogged, frozen segment of telephone pole about six feet long. The decision was unquestionably a joint one, as our decisions were in those days.

We were at least half a mile from where we lived. We wrestled that monstrous object the whole distance—holding it at either end, dragging it with my coat belt around one end, rolling it, constantly changing positions because after a few minutes each strategy that we adopted became unendurable. It was some of the hardest physical work that I have ever done. Neither of us was prepared to give up, and we finally got the thing up our stairs and into her studio and laboriously sawed it in two. He never used it.

VIII

During our second Provence summer in Seillons we walked into St. Maximin one evening and out the other side to see a fireworks display. She always loved fireworks. We both did. All told, by the time we had arrived back at the base of the hill on which Seillons stood and were offered a lift, we must have covered eight miles. By that time we were exhausted. She walked at least as fast as I did, and I have long legs. On another occasion we had to get into St. Maximin before a bank closed, and walked absolutely flat out. I had to struggle to keep up with her.

IX

Her body used to be very flexible. She had no trouble adopting the lotus position. She could tuck her legs behind her head. She could also mould her tongue into various shapes. She was very at home inside herself—in those days.

I forget when it was that she damaged her knee by trying to show friends that she could still put her legs behind her head. That is one of the few things that I ever saw her embarrassed about when I later asked her how the knee had come to be injured.

X

When she was fifteen, her beloved father, Arvid Hoorn, had died at home of colon cancer. Some years later, I don’t know exactly when, her mother, Hazel, had a mastectomy.

Two of her Hoorn uncles, who had been living apart from each other as hermits in the northern woods, were weakened by the deterioration of their nervous systems and had to return to the family home in Fergus Falls where they became bedridden and had to be nursed by their unmarried sister, C.’s Aunt Molly. I can’t remember what name, if any, C. put to the affliction, or whether Molly Hoorn in her turn suffered from it.

Before I met her, C. had worked as a nurse’s aide in the surgical recovery ward of the University of Minnesota hospital. She told me of an old man from the country who had finally come in to have a spot looked at and woke up after surgery to find half his face gone. Someone else had tried to kill himself with a shotgun and only blew most of his face away. This was the ward where charity patients came after “heroic” surgery by Doctors Wangenstein and Lillihigh, whose names I may not have spelled right.

Years later she put a heart-stealing surgeon into her painting “Major Surgery,” and there is an operating theatre in the centre of one of her last oils, the one I called “Lost Garden.” I don’t know what she intended by it or by the title of another of her heart paintings, “Valentine with Love to Christiaan Barnard,” the first surgeon to do a successful heart-transplant.

She said at various times that she would have liked to become a medical illustrator, but that the cost of the training was too high.

In a letter (unsent) in response to a dismissive review of her 1978 Expressionism show by a young local art academic, she wrote, “When -------- has tended as many dying people as I have, I will be interested in hearing what he has to say about ‘life values.’ Till then I suggest he shut up.”

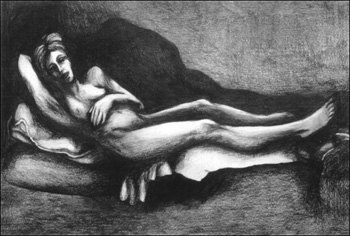

Migraine, 1981, pencil