Drawing

I

The other day [1991] a friend, Bruce Greenfield, said when we were talking about C.’s gardening that she had a sculptural eye. That pleased me, since earlier I had told myself that she saw three-dimensionally.

She was a good, and could have become a very good, sculptor. You can look at the head of the poet Allen Tate, or the head of the old woman, or the figurine of the girl from any angle, and they keep being new—something happens—and keep making sense. She designed, after only a chat or two with an architect friend, the 1982 extensions to our house, and got them right. It was fitting that she should die in the sunroom. It was her creation. It is always a pleasure to be in, the proportions and details being right.

In the Sixties, for three or four years, she taught drawing to architecture students at what is now the Technical University of Nova Scotia. The School of Architecture at that time was run by her friend the always genial, kindly, and supportive Doug Shadbolt, the younger brother of the artist Jack Shadbolt.

She taught a regular class, and she also had charge each summer of a group of twenty or thirty students at a summer sketch camp, which involved their staying in a motel in some smallish Nova Scotia town and drawing its buildings. The students were largely guys, and she got on well with them, and was, I would imagine, an excellent teacher. She really missed those contacts after Doug moved elsewhere in 1970 and she became so marginalized that she felt obliged to leave.

Among the problems that she gave her drawing students to work on in class was this. They had to draw a chair, an ordinary chair which was put in front of them. Then the chair was removed and they had to draw it as it would look upside down and reversed. (I may be leaving out a step or two.) She herself, I am sure, could have done that or any comparable exercise easily.

II

She loved Van Gogh’s and Rembrandt’s drawings above all others, but liked good drawing wherever she found it, and was really pleased to come upon the later drawings of Jim Dine, someone whose Pop paintings I think she had little time for. What she responded to in those drawings, I think, was the simple honest gazing in them, the desire to get the configurations of this carpenter’s tool or those garments right.

Drawing, was in part, for her, a reaching out and attaching oneself to something—a nude model, a Provençal field—and feeling it in its three-dimensionality, and trying to get it right. She did a great many such drawings in the Sixties.

It was also a site where one could experiment formally, introducing all manner of distortions where figures were concerned, but always against the background of a solid world. I don’t think she ever did imaginary figures in the Sixties. There was always a net there, to appropriate Robert Frost’s famous remark about metred verse as opposed to free verse. And it was possible, especially for a student, to be manifestly wrong or inadequate in his or her attempt to cope with the three-dimensional reality that he or she was gazing at.

It was also the most democratic of artistic zones, the one in which so many and such diverse artists across a number of centuries had worked with the simplest of tools.

III

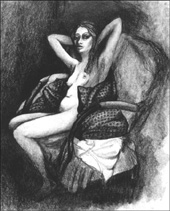

The bulk of her drawings were done in the Sixties. She was marvellous in her figure studies, done mostly at night in the company of Elena Clough and one or two other younger artists and using a professional model or the really beautiful Catherine-Deneuve-like Jeannie James, arrived recently from London with her young psychologist husband, and comfortable out of her clothes before a group. (We learned a couple of years ago that she is now a member of the Polar Bears Club in London, taking winter dips in the Hyde Park Serpentine—a gutsy woman, living on the margin financially and making some very interesting art of her own).

One can see in those drawings C.’s delight in the medium, her continual experimenting with pencil, pen, coloured crayons, her highly conscious appropriation at times of different styles—Matisse here, a touch of Picasso there, and so forth—but always with an eye to the aliveness of the figure, a flesh-and-blood muscled body, and, especially where Jeannie was concerned, the expressiveness of its body language—self-abandonment, pensiveness, whatever.

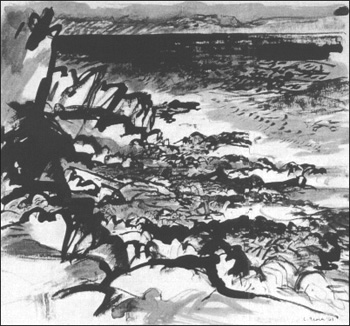

Her early Provence drawings were a bit tentative, and viewy, but once she became at home there visually, especially with the stimulation provided by Bruno and Molly Bobak’s visit in 1966, she became increasingly interested in rendering the textures of things.

You can feel those rough free-standing stone walls, those twisted olive trees and grape vines, that sun-baked soil, those scratchy plants and stubble. They are her own drawings, not Van Gogh’s. And she did further memorable drawings in the even hotter and less hospitable, or at least less comfortable, landscape of Majorca. The following year (1967), in which she shows a strong consciousness of the cultivated, the humanly worked, aspect of the scene—the walls of loose stone, the pruned and shaped trees, the ploughed fields.

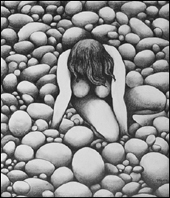

She also, here in Nova Scotia, did superb seascapes, in which she watched and felt and caught the heavy advancing movement of the waves, and how they broke, and the texture of the rough and often seaweed- rocks over which they broke or across which, if the tide was down, she watched them. Almost all of these were done during our numerous early-September stays at the MacLeods’ cottages at Green Bay, near Petite Riviere, about sixty miles down the coast a bit from Halifax.

IV

There are a couple of other aspects of her drawings that I must mention. I am thinking here particularly of the later drawings, done in the Seventies and Eighties.

One is that in several of the pencil drawings of figures in which she filled in virtually the whole surface, if only with delicate shading, she was explicitly concerned with rounding and modelling the limbs, even when (as in the lovely study of a girl leaning upon a species of balustrade against an abstract background), the bodies are strongly distorted. So that one feels, as in the figure I’ve just mentioned, various muscular tensions and resistances at work. She fascinatingly transformed an earlier drawing in this way, introducing some enormous flowers into the picture. She also did a bravura variation on her “Stones” drawing.

The other is this. It is obvious that when she did the relatively few but mostly brilliant drawings with a lot of objects in them and every square inch of the paper worked over, she was seeing those images in her mind’s eye. I mean, she wasn’t doodling or improvising as she went along, and I think she did very little erasing. She saw those scenes, and they were three-dimensional ones, with each object modelled and solidly there in relation to the other ones

V

I can testify to this mode of working with respect to at least one major drawing.

When we were in Ajijic for my third Mexican sabbatical, 1989-90, the winter was uncommonly cold for those parts, and at night, after supper, we passed our time in the living room, where I made log fires in the very efficient fireplace. She was probably not feeling well at this time, you should remember. She had cracked a couple of ribs in a bad fall before Christmas, at least I think it was before Christmas, in a used-furniture store. She had had at least one bad chest infection. Her knee was probably hurting her. And she wasn’t happy with how her painting was going.

Each night for a number of nights, perhaps for two or three weeks, she sat opposite me on the sofa with a drawing board and a large sheet of paper on her lap, and patiently filled in the sheet, starting in the top right-hand corner, as if she were doing embroidery. The drawing now hangs in the hallway downstairs, and it is one of the most brilliant that she did, a rich medley of objects and styles, all perfectly integrated, in which she catches the essence of the yard next door which we looked down on from the flat roof of our house where I worked each day.

The yard itself, belonging to a poor couple, was a medley of foliage, corrugated iron, wire netting, chickens sitting in the large tree, roosters strutting and calling on the shed roofs. She caught it all, and added a stylized, high-rise with reiterated balconies—a building which didn’t exist—and backed everything up with a stylization of the hills that rose behind Ajijic.

On certain areas she daringly superimposed entirely abstract swirling loops, white loops. Which is to say, she had to draw them by means of boundary lines, leaving the page blank between those lines. They were quite narrow lines, too. And she climaxed it all by even more daringly inserting a rooster almost in the middle of the picture, on a largely blank roof, and risking losing the whole picture if the rooster was ill-drawn and a constant distraction to the eye. The rooster, mercifully, is entirely successful, as are the loops.

VI

Essentially she was filling in the total image, with its varieties of shapes and styles, and the constant interplay between surface and depths, that was there for her in her mind’s eye. I think that is very remarkable. And it was a culmination of the kind of seeing that she had engaged in in masterpieces like the paintings Inland and Couples II.

There she had more room for modifications and second thoughts as she went along, of course.

On the other hand, she had had to attend simultaneously to the surface composition, both linear and in terms of colour areas, the three -dimensional rendering of limbs, tubes, flowers, interior body parts, the side-to-side connections between those things, the front-to-back relationships in space between them, the referential accuracy of some of the drawing (these were works that someone interested in anatomy might look at), the various symbolic objects, saw, candle-flames, interior organs doubling as flowers, and, in the case of Couples II, the heavy erotic charge of certain of those objects, and the painful and obviously partly representative tensions between the male and female figures in that marriage relationship.

She succeeded brilliantly, and I am pretty certain that there are no other paintings like them. (No, not Tchelichew’s, not Kahlo’s.)

Tidal Rocks, 1960's, ink