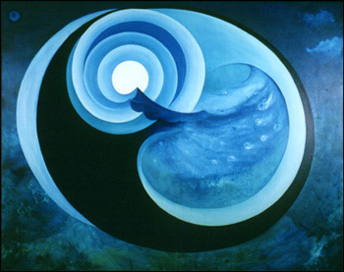

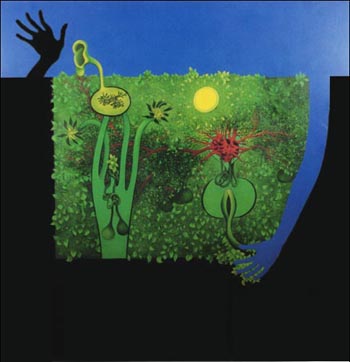

Kissing the Moon, 1968–69, oil

Image-making

I

C. had the power of image-making, unforgettable image-making, the way Van Gogh did, or Munch in The Scream and The Kiss, or Chirico, or Dali.

That’s not a small thing, it’s a very big thing. It’s like being able to write a memorable tune, whether you’re Schubert, or Fauré, or Joplin, or Lennon-McCartney. The CBC is in the habit from time to time of educating us with recordings of works by older Canadian composers, the kind who were born, say, in the 1880s. It sounds like music, it sounds like SERIOUS music, and yet, to a non-musicological ear like mine, it simply isn’t very interesting.

It’s like, for me, the trumpet-playing of Max Kaminsky or Red Nichols, in contrast to that of Bix, or Louis, or Bunk, or Wild Bill Davison at his best. The composers I’m speaking of wrote symphonies with all the appropriate symphony noises, and no doubt put a lot of work into them. But they simply couldn’t come up with tunes the way Beethoven did, or Schubert, or Berlioz, or Mahler, or Elgar, or Stravinsky, or Sibelius, or... well, the list would stretch on a good way.

II

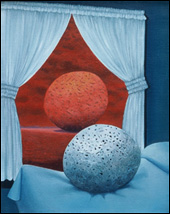

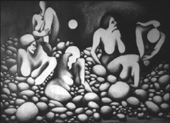

Here are some of C.’s works that immediately assert themselves as images: Grandparents I, Couple I, Couple II, The Journey South, Camouflage, Lamentation, Head Wound, Inland, Major Surgery, The Garden, Ambivalence, Stones, A Taste of Honey, Complacency, Hybrid Study, Squash Blossoms, Beach Girl, The Geology of Fear, Six Women, Geum, The Great Tree.

They beckon one across the gallery even before one knows what they are “about”.

As does that small but very creepy, almost nightmarish painting Mutation, in which one has a weird shifting in scales, the corrugated hose-like tube in the foreground not seeming immediately vast, but then receding into the background and descending to earth like a tornado, which then sends a feeling of motion back along its length and imparts a sense of motion to the part of the tube in the foreground, so that the whole monstrous shape seems to be surging out of the ground and thrusting away into the distance.

It reminds me a bit of those giant sand-worms in David Lynch’s Dune. As I’ve said elsewhere, she liked Lynch very much. She did it before the movie.

Apart from the deliberate echoings in the Grandparents and Couples paintings, these works are all sharply different from one another formally. To see how good they are, one can compare them with works like The Guardians and Sanctuary, which are very fine but do not immediately come off the wall at once, at least not for me. (She herself liked The Guardians a lot, as I remember. I think that she felt it wasn’t properly understood, and that she very much wanted it to be understood.)

Lamentation and Stones could each have been sold several times over. The former would have made a lovely poster-like reproduction, the kind that students buy at those annual or bi-annual sales of reproductions on campus—Dali’s watches, Van Gogh’s sunflowers, Wyeth’s woman in a field, etc. Stones could have been sold over and over again as a lithograph.

III

She never tried to make a lithograph of a drawing. She could have made quite a bit of money that way, I think.

I know that there were political problems for awhile. The only facilities were at NSCAD (the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design), and she was persona non grata down there and too proud to beg.

There were also health problems. During her very successful curatorial trip to Newfoundland in the Eighties, she was offered the run of an excellent print shop there. But she would have had to go out to Newfoundland for a week or two, perhaps in the winter, and I think the idea scared her—scared her where her health was concerned. She had, after all, come very close to dying from an asthma attack during a visit to her sister Milly’s in the late Seventies, and again in Halifax in 1982.

Even so, it is curious that she made, so far as I know, only one lithograph, and that the runs of such etchings and woodcuts as she made, the ones of the poet Allen Tate for example, were very small.

Moreover, the lithograph was one of her few obvious failures, at least in her own eyes. She made it in the print shop of the Art College while it was still near Dalhousie, and I’m not sure how much assistance she had or sought. I rather suspect that she felt that she ought to be able to get it right on her own, and that she was not in fact in full technical command, so that she got a cartoon-like final work rather than the coloristically subtle one that she had been hoping for.

She did the lithograph in connection with some educational activity organized by Mary Sparling at Mount Saint Vincent. She was supposed to be demonstrating or illustrating the stages that a lithograph can go through. Or so I recall, which means that my memory could be playing its usual tricks.

IV

Essentially, though, I don’t think she wanted her works to be multiplied. She wanted each to be its unique, individual self. Or at least she didn’t want to be the one doing the multiplying, and playing the huckster. But she was very pleased when two of her paintings were reproduced on the covers of books by local writers put out by Lesley Choyce through his Pottersfield Press. One of the books was by the gifted and quirky fiction-writer Susan Kerslake, the other, I think, by Lesley himself.

There was something a bit medieval about her attitude here.

On the one hand, the art object was a precious object into which a lot of lovingly and patiently attentive work may have gone. But on the other, I have no doubt that had works of hers been bought and hung anonymously in public places and given a lot of pleasure or food for thought to ordinary people, that would have been satisfaction enough for her.

She wanted people to be interested in the works and what they were “about” in public terms, rather than in the psychodrama of Carol-Fraser-the-Artist.

V

For awhile I was very interested in the novels of B. Traven, who successfully concealed his real identity for a long time and went to his grave without ever admitting to it. I also wrote what I think can reasonably be called a major article on Eugène Atget, who for three decades carried his heavy camera around Paris and its environs and sold the resulting photographs as “documents,” not being discovered as an artist (by the Surrealists and Berenice Abbott) until the last years of his life, and even then displaying no obvious signs of pleasure at this.

I think she understood the modes of being of both these figures, just as she did those of the Douanier Rousseau. and Van Gogh.

She put up a poster in our bedroom with one of Atget’s photographs of a park on it. She was very pleased, too, when we were up in Texas during our recent sabbatical and she found a large and splendidly illustrated book on Rousseau’s art and life on sale at a reduced price. She bought it, and it stayed on our living-room table in Ajijic.

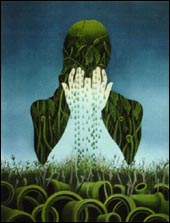

The Garden, 1973, oil