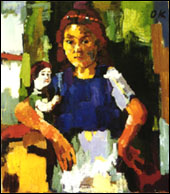

Knight Errant, 1914–15

Kokoschka: Knight Errant of 20th Century Painting

This memorial lecture was given in the Dalhousie Art Gallery on March 8, 1980, and was published two months later in the Halifax magazine Article.

I

At the end of a long life the famous Moravian Baroque philosopher and educator Jan Amos Comenius said, “All my life I have been a man of longing, I have fallen into many labyrinths, my whole life has been a wandering and I have no homeland.”[1] This statement might as easily have been made by Oskar Kokoschka before he died this past February at the age of ninety-three. And it was Kokoschka who suggested to the publisher Sir Stanley Unwin that a new study of the work and life of this persecuted 17th-century revolutionary be written. As a result, John Edward Sadler’s J.A. Comenius and the Concept of Universal Education was published in 1966.

More than any other influence, the humanist ideas of Comenius were to determine the ways in which Kokoschka was to confront life and art. Both these larger-than-life figures were knights errant fighting against great odds in the same quixotic quest for a more humane world through vision. Beginning with his first book, one his father brought from Prague for him and which was Comenius’s Orbus Pictus, a child’s dictionary in which the world is presented and explained in graphic pictures, Kokoschka went on to establish his own “School for Seeing” sixty years later on the principle of Comenius’s concept that “Sight is the first step to insight.”

II

The biographies of Comenius and Kokoschka read very similarly in places, and foremost in this phenomenon is their sharing the personality trait of having so strong and single-minded a sense of vocation that they were raised above adverse circumstances, criticism, and even their own defects and limitations.

Both men lived through first-hand experiences of wars that destroyed their homelands. Both wandered from country to country for long periods of time in a state of exile. And the circumstances of life forced them both into political activism though their instincts were to remain free of such involvement. However, they both saw life in terms of challenges to which the individual must make an adequate response, and with war and its aftermath constantly on the doorstep they could not remain passive. One of Kokoschka’s most important ethical principles was that escapism was not freedom.

Finally, both Comenius and Kokoschka lost much of their life’s work through the senseless destruction of war.

III

These powerful impingements of delusion, frustration, and destruction created individuals of profound pessimism who saw their present situation with horror but never lost hope for the future of the world.

For Kokoschka a second part of his quest was a personal challenge to guard against the emptiness that he found in Dürer’s engraving “Melancholia” which he called “this most disturbing of all expressions of the profoundly human mood of fear and despair.”[2] In this existential battle he was very much the winner, and his full claim to greatness rests not only on his power to transcend his circumstances but on his capacity to take impassioned action when situations calling for it arose.

His life speaks of continuous affirmation. In his painting and graphic art, his plays, poems, essays and books, and also through teaching and in his example of self-generating ability to find and follow his own way regardless of worldly comment, he is a paradigm of integrity unique in 20th-century art.

For Kokoschka, life had to be dealt with on the aesthetic, ethical, and spiritual or religious levels simultaneously. The three were inseparable parts of existence, and so it is that his long life, composed of enough experiences for five or six individuals, became the basic substance of his art. His waking life, his dream world, his visions and his hallucinations were formed into portraits and landscapes, allegories and illustrations of enduring beauty and historical significance.

IV

It is unfortunate that Kokoschka has been labeled a “German Expressionist” by the more popularizing elements in the art world. And it exposes a serious misunderstanding both of his work and ideas and of the two short-lived and rather disorganized German Expressionist movements—Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter.

He did in fact, for a period of one year, 1910, in which he nearly starved to death, become closely associated with the Berlin avant-garde periodical Der Sturm. And while living in Berlin he made the acquaintance of several writers and actors in that cultural circle. But of the artists of the group who made up the Die Brücke movement he says,

I knew few of the Sturm circle personally, and took very little interest in their formal problems or their moral ideas. I contributed no manifestoes, not even a signature. I was not going to submit my hard-won independence to anyone else’s control. That is freedom as I understand it.[3]

However, the importance that the expressionist attitude toward life held for Kokoschka must not be underestimated when considering his ominous beginnings in Vienna and Berlin. For, naturally, the stimulation and support which this revolutionary program of action gave to the young artist also generated an artistic atmosphere which encouraged and energized his emotional involvement with world events and the creative process.

Expressionism as a Weltanschauung is another matter, and he comments at a later time, “There is no such thing as a German, French, or Anglo-American Expressionism! There are only young people trying to find their bearings in the world.”[4]

V

Unfortunately, he was not completely successful in disclaiming his relationship with the German movements, and later, in 1937, he was given the dubious honour of being included in the exhibition of “Degenerate Art” which was organized by the Nazis in Munich. The works of these artists were confiscated and/or destroyed, and Kokoschka estimated that a third of his works had met their fate in this way. In a later reckoning the number of 147 paintings alone was reached.

In Prague at this time, Kokoschka, angry, discouraged, and depressed, retaliated by producing a poster which petititioned that the Basque children who were victims of the Nazi attack on Guernica be given a home in Bohemia. The Prague police immediately tore down these posters for fear of creating diplomatic trouble, but overnight some young people put up new ones again. “From Breslau, the German radio threatened ‘When we get to Prague, Kokoschka will be strung up from the nearest lamp post,’”[5]

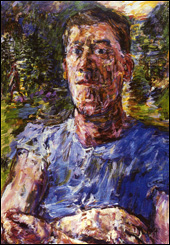

His second and more powerful response was to paint his famous “Portrait of a Degenerate Artist”—a self-portrait in which we recognize a shattered but proud and defiant spokesman for humanity. He also took the precaution of fleeing to England with his friend Olda Palkovská, who was soon to become his wife. He was fifty-two “when in 1938 he escaped from the Gestapo on whose list his name appeared for execution without trial.”[6]

VI

In any case, German Expressionism, as a pre-World-War-I style—especially for Die Brücke artists—means large flattened areas which lend themselves to decorative, heavy, dense configurations, the disregard of painterly quality, and severe distortion and stylization of natural shapes which are often rigid and artificial. It was precisely these decoration qualities of the Jugenstil Movement, so central to the work of Gustav Klimt, guru and president of the Vienna Secession during his early years in Vienna, that Kokoschka had already rejected by the time he went to Berlin. He explains his attitude as follows:

Jugendstil represented a warning to society to change its ways. But in the pursuit of surface embellishment its exponents had forgotten space, three-dimensionality. The idea of a Gesamtkunstwerke, a fusion of all the arts, which preoccupied the artists and designers of the movement, had also governed the work of the medieval builders. But in the Gothic age master builders, stone-masons, sculptors, carvers, painters and glaziers worked in accordance with a higher plan. Not content to mirror the tangible, transient world, they sought an image of Eternity, of Space without limits.[7]

With respect to Der Blaue Reiter, a group which congregated in Cologne for a short period before the war, and with whom Kokoschka exhibited in 1911 in Die Sturm Gallery in Berlin, the emphasis was much more on the “art for art’s sake” movement which influenced the French Fauves and other styles which derived from the scientific potential of the Impressionists—attitudes that Kokoschka instinctively rejected outright the moment he first opened his eyes to gaze upon the wonders of the world.

VII

Neither the more or less chaotic and structureless attitudes of the first group, not the intellectual and decorative art of the second, have anything in common with Kokoschka’s feelings and ideas, which have always been directed toward a continuation of the great expressive tradition of the past. He especially felt a deep spiritual and structural grounding in Catholicism and the Baroque concept, which he interpreted as a style of life. As Giuseppe Gatt says,

He loved nature and he loved the visionary; he analysed forms with passion and at the same time was violently attached to the external world through images that were always objective. He had a geometrical sense of composition and at the same time ‘shouted’ uncontrollably. He loved civil liberty and had a feeling for the tragic; humanism and barbarism were combined in him. . . . Kokoschka was interested in the abstract and symbolic, as well as the typical and the single, in any human situation.[8]

Because of such complexity and diversity of temperament and expressive potential it is much easier to place him in the company of Turner, Ensor, early and middle period Van Gogh, Munch, and the late Rouault, all of whom retained a strong sense of form and composition which disciplines extravagant self-expression and directs the imagination as it struggles to give meaning to experience.

VIII

This kind of individualistic self-expression is an absolute of Kokoschka’s temperament that decides on the conditions which validate and give weight to his work. In this sense he can, and, in fact, MUST, be called an expressionist. His own statement about the nature of expressionism is as follows:

Expressionism... shapes life into true experience. What marks off true experience from all ‘grey theory’ [Goethe’s phrase] is this: that something which is of this world embraces something which lies beyond it—a single moment appearing in the guise of eternity—and that the dull edge of human desires in itself sets off the divine ray of light, just as silence is broke by a cry or as the dullness of habit is broken by the unexpected. Expressionism does not live in an Ivory Tower; it addresses itself to a fellow being, whom it awakens. From the stereotype of man as a herd-animal, which lies within everyone of us, only decisive experience can release us, can lead to humanization. With every such experience our humanity is renewed.[9]

We must see Oskar Kokoschka in context as a lead player in the human drama. He understood his position in the evolving cultural history very well, and he played his part with commitment and great élan. He was never a cool and passive observer, regardless of the issue or the outcome. In the words of J.P. Hodin, “He plunged headlong into the fray, criticizing and ratifying fearlessly, at the same time, separating the essential from the transient, the sick and perverted from the healthy and upright.”[10]

I dare say his candour did not come without a price, and to give full credit to his capacious and generous nature as well as his visionary idealism, I think it would, in many instances, be more accurate if we substituted the label of romantic for expressionist as we review his life and work.

IX

The paintings of Kokoschka fall naturally into the three subject categories of portrait, landscape, and allegory.

However, because of the dynamic functioning of both conscious and unconscious symbolism, many of his portraits and landscapes acquire their own kind of allegorical significance, which is very different from the content of his large historical allegories.

Throughout his long life, Kokoschka always thought of himself as a “seeing observer of nature,” and be it portrait or landscape he always worked in the presence of his subject. This was to him a statement of active participation in the world and resulted in the kind of vigilant observation which could capture those fleeting details of reality which are essential to an image of inner spiritual life.

This alert vision, plus the influence of painters like El Greco, Van Gogh, Tintoretto, Titian, and the Austrian Franz Maulbertsch (1724-96), created a dramatic combination of sensuous realism and spiritual abstraction which is personal and rare.

There was nothing contrived or synthetic in his method. The only mysterious element in it was that contributed by genius, and obviously the direct and spontaneous manner of working which he describes in the following statement is merely a front for a profoundly complex activity:

I usually start my paintings without having done any preliminary drawing: and I find that neither routine nor technique is of any help. I depend very much on being able to capture a mental impression that remains behind when the image itself has passed. In a face I look for the flash of the eye, the tiny shift of expression which betrays an inner movement. In a landscape I seek for the trickle of water that suddenly breaks the silence, or a grazing animal that makes me conscious of the distance or height of a range of mountains, or a lonely wayfarer whose shadow lengthens as evening falls.[11]

X

Kokoschks chose subjects in keeping with his baroque vision of life. His portrait sitters possessed strong and dramatic elements of personality and often were political or artistic figures of consequence. In landscape he was attracted by the immense spread of harbours and cities and the heroic monumentality of mountains. In both instance events of his early life played a determining part in these choices. About portraiture he writes:

Art Nouveau basically ignored the portrait; my surmise is that Darwin’s theory of evolution reduced too shockingly the distance between us and the related species of primates. The sense of familiarity and intimacy within mankind gave way to a feeling of alienation, as if we had never really known ourselves before. I myself was more affected by this than I would admit, which is why, to confront the problem, I started painting portraits. I wanted to have a really good look at people, to watch their behavior, to get to know the nature of the society in which I had to live.[12]

And his wartime experience of lying severely wounded, half buried in mud, awakened in him a determination to paint the world from a high viewpoint with great breadth and immensity of space. With this commitment he traveled throughout all of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East painting vast landscapes in which the visionary tensions of space remind one of El Greco’s “Toledo.”

As he grew older, his conviction that the elimination of the illusion of deep space represented a rejection of an ideal vision and a limiting of possibilities deepened into an unshakeable belief. What he sought was a “space without limits.” A space which created an idea of eternity.

XI

It was inevitable that his career which began with the creative struggles to gain control of his personal life through symbolic means and self-dramatizing should culminate in the great allegorical history paintings of his later years. The thematic imagery and the mythologizing power of “The Prometheus Saga,” “Thermopylai,” and “Herodotus” give a small indication of how inexhaustible and profound his source of creative intuition actually was.

In between the early autobiographical works and these monumental later pieces are the series of religious paintings of 1911-12, the marvelous symbolic animal portraits of 1926, and the war allegories painted during his exile in London between the years 1938-47.

Summing up the last years of his life, Kokoschka said, “I find that visual experience is all that remains to reconcile me to this ‘best of all possible worlds’.”[13] However, his irony here is not to be construed as pessimism, for after the war and considerable attention in the form of international exhibitions, he swung into fierce new activity and set out to conquer yet another form of artistic experience.

In his large and important allegorical history paintings he has followed his instincts and imagination back to the great classical art of pre-Christian times. Just as Edvard Munch found healing and inspiration by contact with nature, Kokoschka found it in his discovery of Greece. Like a kind of sensuous and intellectual omnivore, he devoured the literature (which he already knew from his earlier reading) and philosophy, the architecture and sculpture of the ancient culture, and appropriated the themes and forms for his own baroque-humanist system.

The significance of this for his painting is clear.

His themes are overtly narrative for the first time as the subjects are taken from mythology and early history. The images are bathed in the strong, hard, purifying light of the Aegean, and the fourth dimension of movement brings these images to life. This new excitement, like a new adventure in his quest, is made visible in the “Thermopylae Triptych” of 1954, the theme of which is the struggle of the Greeks against the Persians.

However, the spiritual content relates to the present as once again Kokoschka becomes a cautionary artist who uses the allegory of a hopeless struggle in which the Greeks are depicted as defenders of the people of Europe against the Persians, to warn of the impending hopelessness of the survival of our own human vision.

XII

Kokoschka wrote many plays, poems, essays, lectures, stories and memoirs. He illustrated both his own writings and those of his contemporaries as well as the classics of literature and mythology. He edited journals and made political posters, and he founded a famous art school and at least one refugee foundation. This is all activity which helps to record the experience of his exceptional life and the momentous times in which he lived.

Yet it is as a painter that Kokoschka has left the most profound and enduring impression on the history of vision. For while the other moderns were busy with technical problems and formal concerns, he developed an art which is basically a romantic expression of his own personality, and which will undoubtedly become an important humanist document.

As a revolutionary artist with one foot deeply embedded in the great visionary Baroque tradition of the 17th-century and the other in the dramatically evolving unknown future, he is unique in the history of 20th-century art.

Always a loner, as existential being he assuaged the weight of his risky and melancholy career by a passionate commitment to an art which was both established in tradition and yet made completely free by the visionary imperatives of non-rational creativity. He greatly disliked spiritual uniformity and the domination of formal methods and techniques, which he saw in modern art as a product of man’s withering capacity to respond to experience and the diminishing of his inspirational aptitude.

That he never really despaired in the face of the demands of such an idealistic and unfashionable position says much for the quality of his inner resources. His strength and staying-power form a model of integrity which assures his place in history.

XIII

Throughout his career as a portrait painter Kokoschka portrayed many aging and aged men, but seldom did he show himself in later years. However, there is a last self-record, done in 1970, and I think it is appropriate to quote his own comments on Rembrandt’s late self-portrait which hangs in the National Gallery in London:

I saw it properly for the first time on one of those London winter days when, without the means to survive, I felt myself to be on the outer fringes of human existence. The picture gave me courage to take up my life again. Rembrandt was suffering from dropsy; his eyes ran continually, and his sight was failing. How firmly he studied in the mirror the end of his own life! The artist’s spiritual objectivity, and his ability to draw up a balance-sheet of his own life and give it pictorial form, convey themselves powerfully to the beholder. To look at one’s own physical decay, to see oneself as a living being in the process of changing into a carcass, goes far beyond the revolutionary Goya’s “Plucked Turkey”, a dead bird in a still-life. For there is a difference, after all, between being involved, oneself, and seeing it happen to another. A human spirit is about to be extinguished, and the painter records what he sees.[14] (my emphasis)

And now the record is finished. With a health that was much deeper than his neuroses, “Mad Kokoschka” the super-Fauve grew into a prophetic old man who is often referred to as the conscience of 20th-century art. He leaves as his legacy, as it was left to him by Comenius, the divine quest to struggle for a more human world through vision, and to safeguard against the perils of “Melancholia.”

Carol H. Fraser

[1] Quoted by Frantisék Kozík, The Sorrowful and Heroic life of John Amos Comenius, Prague, State Educational Publishing House, 1958, p. 178.

[2] Oskar Kokoschka, My Life, translated from the German by David Britt, New York, Macmillan, 1974, p. 212.

[3] Ibid., p. 67.

[4] Ibid, p. 37.

[5] Ibid., p. 152.

[6] Anthony Bosman, Kokoschka, London, Blandford Press, 1964, p. 10.

[7] My Life, p. 22.

[8] Giuseppe Gatt, Kokoschka, London, Hamlyn, 1970, pp.14-15.

[9] “Der Expressionismus Edvard Munchs’”, quoted by Remigius Netzer, Postcript to My Life, pp. 216-17.

[10] J.P. Hodin, Oskar Kokoschka: The Artist and his Time, Preface, London, Cory, Adams & MacKay, 1966, p. xi.

[11] My Life, p.33

[12] Ibod., p. 36.

[13] Ibid, p. 197.

[14] Ibid., p. 210.

New York, Manhattan with the Empire State Building, 1966