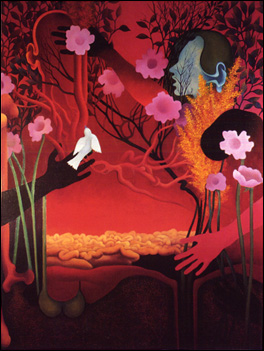

The Equilibrists, 1972–1985, oil

Other

I

They met in February or March 1956 and were married in September. The marriage lasted.

What did she get from him? I mean, he was no great shakes as a lover, and went at times into terrible sullen angers in which he would barely speak to her, or literally not speak at all, for two or three days at a time. I know that one trip by car to New York with their friend Jim Cherry was spoilt for her in that way, and there were a number of similar occasions when he was quite impossible because she had failed to respond to some statement of his with sufficient enthusiasm or concern.

He also had medical problems that made things inconvenient for her, particularly in Halifax. For all but the first two or three years of their marriage he was on a regimen of cytomal (a thyroid substitute) and the barbiturate sodium amytal, taken twice a day, and not, in their effects, covering the whole 24-hour period of a day.

Hence, for a good while, he did not get up until ten-thirty in the morning, which effectively messed up her day since she insisted on making breakfast for him and eating it with him. He also absolutely had to have his period of seclusion between 5:00 p.m and 6:30, when he lay down upstairs and had a drink and read thrillers.

II

He always wanted her to light up, to be instantly there for him, to smile at him when he came into the room at some gathering. He wanted her to be enthusiastic about the typescripts that he gave her to read from time to time. He had never had, at least discernibly, the respect from his father that he craved. He was chronically insecure. When around 1985 she agreed with his Cambridge publisher Michael Black that his new book could not be published as it stood, he was deeply hurt and never really talked with her after that about what he was working on.

At times, earlier, he had bored and bothered her by going on and on at the dining-room table about the progress, or rather the shifts in direction, of the book that became America and the Patterns of Chivalry, and trying to tell her about the Civil War, American labour history, and so on. He kept finding out about things that he had known little or nothing about before, and then assuming that she would, and should, be interested in them.

At one point, too, he became obsessed with censorship. I’m sure she was bothered as well as bored at times by his disquisitions, and felt that he was stepping across dangerous boundaries. She also got fed up with some of his complaining about Dalhousie politics, where at times he was very much an outsider.

I shall probably think of further minuses. So, what were some of the pluses?

III

Well, he really did care about art, and it didn’t just begin when they met.

I imagine he had been taken to the National Gallery before the War, though he has no recollection of seeing anything there. While he was still a schoolboy, he had gone to the National Gallery on his own, and perhaps to the Tate, and had ventured into a few West End galleries, at one of which he had been scandalized when told how much a flattened, child-like painting was selling for. He admired the etchings of Frank Brangwyn at one gallery, and wrote a poem based on one of them.

He went to the important Picasso/Matisse exhibition just after the end of the war, and particularly liked those now famous Picasso paintings of a candle and a few objects on a table, and the like. He felt the Occupation in them. He went to the big Van Gogh exhibition at the Tate, and particularly loved the outdoor cafe scene. He went to the big Chagall exhibition at the Tate

When he was an undergraduate, he was thrilled by a copy of George Grosz’s Ecce Homo that a friend owned, and also by Piranesi. He spent some time in the Bodleian Library poring over the folio volumes of Piranesi’s Roman etchings and his Prisons. He thought of writing on both artists (separately, I mean).

He read Robert Melville’s article on Francis Bacon in Horizon, and was thrilled by such Bacons as he was able to see He was able to see some of the grey curtains and screaming Popes at the Hanover Gallery, but was especially excited by the strange spatial dislocations and ambiguities in The Magdalene, as he was by the then solitary garden painting at the Tate.

He went to a public lecture in London by the art critic Eric Newton, and was excited by his analysis of the formal structure of a painting of three muses or graces or goddesses floating in a circle with linked hands. He read Kenneth Clark’s Landscape into Art enthusiastically, and stood in front of the Claudes in the National Gallery, which he very much liked, trying to see them in terms of foreground, middle ground, background. In l951, he stood in front of Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Somerset Maugham, offering a slightly frenetic but for all I know accurate formal analysis of the painting to one or two friends.

He was never afraid to have opinions, particularly after he discovered Ezra Pound on his own in high-school. He went through the Tate telling himself that a lot of the paintings were awful, the Pre-Raphaelites no doubt among them, but that some of the late Turners, such as the music room at Petsworth and the nacreous painting of the beach with a cow or two on it were lovely.

He read Nikolaus Pevsner’s An Outline of European Architecture very carefully and looked at buildings with its help, especially baroque ones.

IV

He loved movies.

He had gone avidly to movies as a kid, and images had embedded themselves in his memory—a hand with a gun in it emerging through the gap between two curtains; two lines of Chinese soldiers facing each other with their guns in the misty dawn in The General Died at Dawn; the sinisterness of The Most Dangerous Game, which he saw before the 1939 war under the title of The Hounds of Zaroff.

Near the end of the war he discovered foreign movies in the two or three London theatres that showed them, and gazed at the stills in Roger Manville’s Film, and yearned to be able to see them. One of them he had in fact seen—Battleship Potemkin, which one of his schoolmasters had screened at his home for a few kids as a holiday treat. When he was a clerk in the R.A.F., he had single-handedly created a nominal film society, and bought in movies that aircraftsmen paid to see on Saturday afternoons, among them Un Chien Andalou, M, Zéro de Conduite, and The Italian Straw Hat.

He also loved photographs, and in 1947 bought a primitive 35-mm camera and was very serious about trying to compose with it, though I don’t know that he took more than a few pictures.

V

On a visit to Dublin in 1949, his portrait was painted by the artist Nano Reed, at her request. It was for him a fascinating experience, sitting there as she gazed expressionlessly at him and made invisible movements of her hand behind the canvas on the easel. He never forgot the strangeness of the few thick dark brush strokes when he was permitted to look at the canvas at the end of the first session.

The finished picture was expressionist, probably a bit in the manner of Jack B. Yeats, and made him seem much more interesting and vigorous than he felt himself to be. A reproduction of it appeared a year or two later in the Irish magazine The Bell.

VI

I don’t know when he first became aware of the Surrealists, but it may have been when he read George Orwell’s essay on Salvador Dali around the time it came out, maybe 1944. He was particularly taken by Orwell’s remarks about the dead mannequin in a taxi with snails crawling over her. Later, when it first appeared in England, he read Henry Miller’s The Cosmological Eye, and yearned to see Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or. When he was in Paris in 1946, on a summer exchange visit, I’m pretty sure he discovered the Minotaure bookstore, where in 1949 he bought Breton’s Surrealist Manifestoes and the first volume of Sade’s Juliette.

When he was in the Air Force, he sat in the Salvation Army Canteen reading Herbert Read’s collection of essays and reproductions called Surrealism. He went to the just-off-Bond-Street exhibition of the paintings of the Temptation of Saint Anthony commissioned from a number of Surrealist artists. Ernst’s and Dali’s were among them, though it was the latter that he remembered.

He had also looked at and remembered a book of Kollwitz’s prints.

VII

So, as I say, he really did care about art, and knew a bit about it, and perhaps that mattered to C. He also had a good eye formally, as his best photographs show, so that if she asked his opinion about a painting that she was working on, he could usually sense when some area of the painting felt not quite right, even though all he could say was just that, or that it seemed a bit cluttery, or a bit thin.

He had no suggestions to make about how the problem, which she usually agreed was a problem, could be solved. He had opinions about lots of other things, and didn’t hesitate to inflict them on her, but I think that he was basically hands-off where her art was concerned, and that she appreciated that.

He never, I think, tried to talk about the content of a painting—never asked her what it “meant.” She may have appreciated that too, even though I know she thought him very dumb when he once tentatively suggested that she might consider removing the small nude female figure lying on her side in the glove compartment in the painting South.

He never felt personally threatened by the contents of a painting. The tensions and antagonisms on display between the figures in Couple I and Couple 2, and the harsh inorganic intrusions in them are pretty painful. Moreover, the figures in Couple 1 look pretty much like C. and himself. But all he saw were two exciting paintings.

I think she felt he had a good eye. From time to time, when she was preparing a show or putting together some works on paper to send away, she would lay out a lot of pieces in the floor and ask which he thought should be included. Their opinions were usually fairly close, so that basically he was confirming feelings that she already had. After all, he had received a marvellous education in art over the years from looking at her works and noting, on such occasions, which ones she herself strongly liked.

VIII

He seldom offered suggestions about the course of her work. I know that once or twice he wondered to her about the possibility of her doing some print-making. He had done some elementary arithmetic with respect to the prices that one or two local artists asked for their prints and the number of prints in an edition (e.g., $100 x 100 = $10,000). And she had told him of the popularity of her drawing Stones.

But she swerved away from the topic, and he didn’t pursue it, though he could nag her endlessly about matters unconnected with art, such as “When are you going to make that bead curtain for the living room door that you promised???”

I think he also tentatively raised once or twice the possibility of her doing a few commissioned portraits. She had talked about a number of modern portraits in her MFA thesis and in her lecture on Kokoschka, and he imagined that there might be a few well-to-do people in Halifax who would like to be immortalized by her. But again, the suggestion dropped dead, without argument.

IX

I think that basically he felt that, where what she said or felt was concerned, “What I say once, with conviction, is right”. He tried to sense what she wanted, and what she was trying to do, and where she wished to go, and to support her. He was arrogant intellectually about a lot of things (though timid at the core), but he was humble in front of her art. Moreover, he almost always, with regard to specific works, felt that she was right, or might very well be right.

X

He was impatient. When they went through galleries together, she usually proceeded slowly, looking at every picture, while he charged ahead, looking for works that leaped off the wall for him and that he could bring to her attention. When he rejoined her and she was interested in some work that his eye had slid over, it immediately became more substantial for him. Contrariwise, when she wasn’t interested in something that he had liked, he had second thoughts.

They talked quite simply, as I recall. He: “I sort of like that.” She: “Yes, that’s nice. That’s quite nice. Nice hands.” Or; He, “I think that’s lovely, that’s just lovely. Simply gorgeous.” She (purring): “Mmm!” Or, He: “It’s funny, I hadn’t realized how loose Magritte’s brushwork could be at times.” She: “Oh, yes, he could work quite fast.” Or, He (after she had stood silently in front of a picture for several minutes) “You like that?” She: “Mmm. Yes”

XI

He was probably annoying at times because he felt that she was so obviously good that it must surely be only a matter of time, and not a long time at that, before she was “discovered “ and her art was seen at its true worth.

He kept hoping for a deus ex machina, some visiting art critic or connoisseur, to see her work and be excited about it. (It had been a bit of a thrill back in Minneapolis when Vincent Price had bought one of her paintings, a small forest scene, though it was hard to think of Price as a serious actor.)

He thought she could go to Toronto or Montreal or New York with a portfolio and be snapped up by a gallery. He thought that a show like her glowing paintings of stones would sell out overnight. She was much more realistic than he was.

XII

But at least he loved her work himself, and contrived to get a number of her pieces onto the walls of their Oakland Road house, with promises, given piecemeal, that this or that work wouldn’t be sold if he didn’t want it to be. And he went into one of his sullen furious withdrawals when she told him blithely that she had just sold to a friend a particularly lovely small painting that she had done of the landscape on the road from Tepoztlán to Cuernavaca, with the thin white ghost of Mount Popocatapetl hovering in the background.

XIII

He genuinely loved a lot of the artists that she did, such as Van Gogh, Bonnard, the later Rembrandt, Brueghel, Ernst, Magritte, Rousseau, though he could never really tune in on Chagall or Beckmann or Marin. She in turn was never stirred by Hopper and held Goya at arm’s length, something that always puzzled him.

He bought books for her, among them the book of Medieval drawings that she drew on when she did her big gold painting Figs and Olives, and various books of fantastic art. He also took her into one or two bookstores in Paris that were on his wavelength, and where they bought several books together, such as Robert Hughes’ excellent book on the sun in art, which was going cheaply.

XIV

He was strongly interested in aesthetics for awhile, and he liked to think that his position was reasonably in line with hers, so that what he said when they talked about the sort of art theorizing and criticism that was to be found in journals like Art News, was supportive of what she was doing. I’ve no idea what in fact she thought and felt about what he said, and certainly her eyes never lit up at times in an I-never-thought-of-that! fashion. But perhaps it mattered to her to have someone in her corner.

XV

In the later Seventies his obsession with completing his chivalry book which he thought of increasingly as his Vietnam, something that he had embarked upon lightly and then become hopelessly bogged down in, drew him apart from her into areas of history and sociology that she frankly admitted she had no interest in.

In particular, she wasn’t interested in American history. I think that she had a lot of trouble seeing herself as An American in a wide-screen way. She was a Lutheran Minnesota Swede. The claims and counter-claims and finally violences of New England and the South had never imprinted themselves on her when she was young.

XVI

In the Eighties, particularly at the time of his concern with censorship and his reachings back into his childhood obsession with images of horror and violence, he became somewhat questionably concerned with mere revolt, regardless of where it was coming from; more sympathetic to taboo-breaking; more obsessed with horror movies, especially splatter movies. By 1982 or ‘83, she was moving into the hors-série quietude of her watercolours, and didn’t really want to talk much about art at all, certainly not theoretically-polemically.

But a fair amount of talking had gone on in earlier years.

XVII

Her friend Dorothy Anderson-Galloway (then Dorothy Bruhl) recalled recently in a letter that C. had told her, “I’ve met a grown-up at last. A real grown-up. Not like those hopeless boys” (by whom I suppose she meant the Oak Street group). I have difficulty seeing JF as a real grown-up, either then or later. He seems to me to have been chronically immature.

What might she have seen?

XVIII

Well, I suppose you could say that he was playing for real. As someone who as it were carried Lawrence in his rucksack—particularly The Rainbow and Women in Love—he very much wanted a permanent union, and felt or knew that if the wrong kind of marriage would destroy him, the right kind could save him. He insisted (at least she claimed later, amusedly, that he did) that she read Women in Love. I think she wasn’t all that impressed by it.

He read critically and very seriously, and with a desire to appropriate and incorporate into his own being what he read, or at least those things to which he could give assent. He was concerned about God and values.

XIX

When they met, he was taking a graduate Philosophy class in Spinoza, in which the instructor worried away at a handful of technical problems and passages. The text was the Ethics. Most of the small class got low marks for the mid-term, JF among them.

After that he worked harder at trying to understand Spinoza (with the aid of Stuart Hampshire’s Penguin volume on him) than he had ever worked intellectually in his life before. Spinoza seemed to him very great, and remained a presence for him for years, even though he forgot so much of him. Spinoza’s central concept of the conatus, that drive of each thing to persist in its being, figured in his later essay on Wuthering Heights, and he was very pleased to find it appearing again in Borges, whom he read seriously in the Eighties and wrote about.

As someone with a fragile ego, always in danger in those years of being overwhelmed by accusations that would leave him with feelings of guilt and worthlessness from which he could never escape, he was grateful for Spinoza’s insistence upon the primacy of one’s own being. One should not allow oneself to be destroyed—or destroy oneself— in the name of some system or constellation of values that reduced one to an abstraction, a sort of Lowest Common Denominator.

He felt a good deal of guilt at that time about the harm that he had done to two women; and a theological writer like C.S. Lewis could still throw him off balance.

Anyway, when he talked with C. in one of the cafes just off campus about Spinoza, and tried to explain what he was finding there, he was obviously talking about something that mattered very much to him. He was not simply “doing philosophy.” So too when he read two or three works by Kierkegaard after he had picked up the name from her.

Another thing in his favour, perhaps, was that he didn’t like jargon that he didn’t altogether understand, and emphatically didn’t want to slip into the kind of theological reading and discoursing in which one swam comfortably among Kierkegaard, Tillich, Barth, et al.

XX

In his dealings with literature and aesthetic theory as a student, he was rarely neutral or indifferent. He cared deeply about F.R. Leavis, at that time so little valued in America. He “discovered” B. Traven, at that time virtually invisible, wrote an article about him, enthused about him in conversation. He wrote a very long and would-be complete account of the life and works of the architectural third Earl of Burlington for Samuel H. Monk’s great seminar on Jonathan Swift and his contemporaries. It was months late, and in different circumstances could have been an M.A thesis.

Both he and C., who had taken a three-term course from the aesthetician John Hospers, thought highly of R.G. Collingwood’s Principles of Art. As did their friend Alan Donagan, from whom JF took a one-term course. During the second year of their marriage JF wrote an encyclopedia article on twentieth-century American and British poetics that his department advisor had passed on to him. He really cared about theory.

XXI

When C. and he were in England in the summer of ’57, they made a pilgrimage to Chiswick to see the rotunda that Burlington designed, and the gardens laid out by his friend Kent.

In 1962 they made a similar pilgrimage to Farnham, in Surrey, to see where George Sturt’s wheelwright’s shop had stood (the building was still there, but now a garage) and to visit Sturt’s cottage. He had done his thesis on the rhetoric of Sturt’s books on English rural labouring life.

A Margaret Rutherfordish lady came to the door when they knocked. When JF started to explain why they were there, she said, “Oh, I know all about Georgie Sturt!” and showed them around the garden where Sturt and his gardener Bettesworth had worked, and pointed out the spot where Sturt had gathered some of his material. The road up from the brook flattened out at that point, and the village women who had been down there washing things or fetching water would pause there and gossip. Sturt, hidden by his hedge, listened and later made notes.

She was amused by that, in a friendly way. She also showed us the scullery where Bettesworth had to wait when he came calling. He was not allowed inside the house itself.

I think C. enjoyed such doings—enjoyed JF’s enthusiasm. He was not a pedant, at least not then. He knew, in the sense of remembering accurately, very little. He always had to work things out as he went along.

XXII

In the fall of 1956, during the first year of their marriage, JF and George Levine, a fellow graduate student, sat at the Frasers’ kitchen table and talked speculatively and half ironically about starting a magazine, but by the end of their conversation the idea had drained away into the sands.

Next day, or a day or two later, another graduate student, Don Jobes, sat there with C. and JF having coffee, and JF brought up the idea of a magazine again.

Don, who had been a seminarian, and came from a background that C. understood, was in some ways a self-parodying figure—sported a moustache, smoked a large pipe, was brusquely macho in manner, later bought a large bull-dog.

But he was basically very serious, and detested the genteel role-playing and rituals of graduate school. He picked up on the idea, he and JF went to call on George Levine, who now responded much more positively, and after that, I forget by what route, Al Boersch and Tom Roberts were brought in, neither of whom JF knew.

XXIII

After a lot of discussion and preparation (which C. was not in on directly) the first issue of The Graduate Student of English appeared in the fall of 1957, and eleven more issues followed, all on schedule.

During all that time JF lived and breathed GSE. They were the richest years of his life, and the friendship with Tom Roberts that developed out of it was his most precious friendship. It was a period of constant dialogue, or of the kind of thinking in which one is mentally always looking forward to speaking to someone about something, or half speaking to them inside one’s head. (What about an article on such-and-such? How about approaching so-and -so for a review? Wouldn’t this passage make a great filler?)

The magazine was typed single-spaced on multilith sheets, the pages were run off by a printer from those sheets, the editors then collated those pages by hand, stapled them together, inserted them inside the cover, stapled the sheets and cover together, inserted the copies into addressed envelopes, carried the bundles of envelopes to the post office, and mailed them off. The normal printing was probably around 400 copies.

All this was done without benefit of any grants. The Department’s assistance was limited to allowing JF, Tom, George, and Don, in their capacity as teaching assistants and part-time instructors, to share an office during the magazine’s first year, and JF and George to do the same during its second year, after the others had gone to jobs elsewhere. In its third year, JF and Dick Cody ran it.

XXIV

C. was always there as one of the collators and staplers. After a bit she became the magazine’s business manager.

She wrote an article for it in which she tried to explain the appeal of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet for adolescent girls. I suppose it could be considered an early example of reader-response criticism. Years later, Tom Roberts reported to JF having overheard, at some function of his department at Connecticut, the novelist John Seelye saying, “The best thing ever written on The Prophet was by some girl in the old GSE.”

She also wrote a brief review of one of Alan Watts’ books on Zen, and in a pseudonymous letter castigated JF and the Paterian aesthete Peter Thorslev for being so absolutist in a controversy they had in the magazine’s pages.

XXV

I think she enjoyed this nexus of male activity, in which there was a lot of debate, and in which all the editors, as long as they remained editors, genuinely desired the good of the magazine.

Moreover, it was a magazine with missions. It wanted to have its effect on graduate studies. It wanted to make them more rewarding and meaningful for students. It wanted to provide practical information about things that normally weren’t talked about, such as jobs and how to get them.

And it was set more or less strongly against the pieties of the American New Criticism, especially the Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren variety.

Tom Roberts wrote a couple of critical articles, one of them on Joyce Kilmer’s poem “Trees,” that testified to his awareness of the Russian Formalists; also an article about the desirability of starting to take comic strips seriously. JF did an article on the rhetoric of Descartes’ Discourse on Method that seemed to him years later to be a species of deconstructionism.

XXVI

After appropriating C.’s 35mm Argus camera, JF soon became a passionate photographer. He bought a Leica IIIC, a light-meter, and a stainless-steel developing tank, and learned the rudiments of printing in the Art Department’s darkroom. He took lots of pictures, and made lots of prints.

XXVII

A bonus for C. was the friendship with Gene Wilcox that grew out of this. Gene, who I think was part Native American, was three or four years older than JF, and had lived hard, at one point being a very heavy drinker. He had worked, perhaps he was still working, as a house painter.

But he had also discovered photography, and I’m pretty sure he took a course at the university, probably from Jerry Liebling, who had studied under I forget who, who had studied under Paul Strand. Gene, who worked exclusively with a large camera like an overgrown Rolliflex, was a “pure” photographer who did a fair amount of work down in the skid-row area of Minneapolis documenting old buildings. He became a superb printer, and taught classes at the university.

He was a big man, and acromegalic, with jutting brows and nose and chin, and large hands. He was the gentlest man JF ever knew, and was utterly without affectation. He deflated JF’s pretensions, when he was being pretentious, with a wry remark or a bit of body English with his eyes and eyebrows. C. liked him a lot. He was one of the touchstones of virtue for her and JF.

He was happily married, and had a beautiful blond little daughter, whom he obviously adored.

In 1970 he hanged himself in the basement of their house out at White Bear Lake. His illness had flared up again, and a bungled operation on his pituitary had left him with a speech defect so bad that it was hard to follow him, and a tremor that made it impossible for him to continue working at photography.

XXVIII

JF’s photography probably provided a kind of bridge into the circle of C.’s art activities.

He wasn’t simply a student of literature. He could talk about photography a bit with Allen Downs, who taught in the department and was the husband of her friend the painter Phyllis Downs. He took photos of fellow students of hers like Bill Bartsch. He was the official photographer at the wedding, in the couple’s apartment, of Carol Lind and the African-American artist Mel Geary, and later took pictures of Carol and her baby. He photographed C.’s bust of the poet-critic Allen Tate.

Moreover, he took some good photographs—good enough for two of them to be exhibited at the State Fair. Another, the double portrait of C. and her mother, was in a little group show at the Minneapolis Art Institute, and the Institute offered to buy it, an offer he declined since the price seemed to him insultingly low—insulting to photography.

He also took part in a three-man show in the Lind-Geary apartment. The other two persons were Gene Wilcox and the reclusive and intense artist John Beauchamp, one of the very few people, I think (along with her Aunt Molly), who had the power to intimidate C. by the sheer force of his convictions.

JF was often a derivative photographer. One can tell when he had been looking at Cartier-Bresson, at Robert Frank, at Weston, at Atget. And lot of his photos are characterless. But at his best he took a number of strong warm photographs, and C. liked some of them very much and hung two of them, framed, on the Oakland Road walls. She also at one point in Oakland Road went through the prints and negatives sorting them into groups for storage purposes.

XXIX

I think it mattered to her to have him documenting their environment in Minneapolis and later in Seillons, the village near Aix-en-Provence where they spent two important summers. I don’t know what effect it had on her art when he virtually abandoned photography in the later Sixties after they moved into the house on Oakland Road. (He could no longer spare the time for printing. He also could no longer summon up the energy necessary for doing candid photography and invading the space of strangers.) Perhaps it made easier her move away from realism.

XXX

For awhile he continued to document her work for her, but when his Leica was stolen in the early Seventies, she bought herself an Olympus, or was it an Argus?, with a macro lens, the kind with which one can do normal photography but can also be used for extreme close-up work. The built-in light meter made it much easier to use than the Leica had been.

She documented her work and made a lot of slides for talks that she gave. But though she did some close-ups of flowers, I don’t think that doing photography really interested her.

XXXI

When the two of them married, a couple of their acquaintances, as they heard later, gave the marriage six months at best. It lasted thirty-five years, and during the last week or two of her illness JF was able to tell her, with the feeling that she might like to know it, that he had been completely faithful to her ever since they met, to which she slowly and softly replied, almost as if it didn’t merit saying, “I---know---you---have.”

XXXII

I realize that I have stayed away from the deeper areas of her heart. I feel a bit obtuse about this.

In the catalogue for her great 1977 exhibition, she referred to him as her “husband and muse.” Her closest friend, Mimi Cazort, told me not long ago that in the early Seventies, after having earlier had a no doubt painful divorce, she learned from C. that a woman could in fact live together lovingly with a man. I realize that the kinds of things that I have been talking about don’t explain love. I still don’t know why she should have loved him.

He told her, I forget when, but relatively early, that he was really three different people and should properly say “We” rather than “I”. They kept that as the kind of joke that in fact copes with a reality. At times, when he gave her a present, the card would say “From all of us.” I forget what the different selves were.

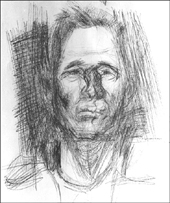

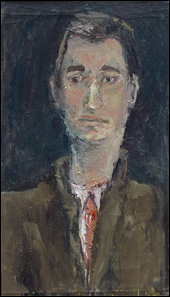

A superb early pencil portrait of him, which still hangs in the kitchen, makes him look like the young Robert Graves, the poet, which is to say strong and tough, a fighter. In an early oil painting of him, which hangs over her desk in the sun room, his face is long, his shoulders narrow, everything is drooping. There is almost no point of contact between the works. But perhaps they caught different aspects of him, and she could live with those differences.

Those were the only portraits that she did of him, apart from a very late one done in Ajijic and paralleled by one of her which she had difficulty with.

A Giacometti lithograph, a drawing of a skinny elongated figure seen from the side, hung on their walls for many years. They treated it as a sort of portrait of him. On the wall of her studio, above the light-switches beside the door, is a very nice photo of him, young, bearded, and sincere- looking, that she took in Minnesota when they were on their vacation up at Long Lake.

XXXIII

They both had a sense of humour.

Above his desk in the 14th Avenue apartment in Minneapolis, in the room that also served as their living room, there was a coloured photo that he had cut out of Life magazine of a giant tortoise, no doubt in the Galapagos Islands, taken head on, the head half withdrawn, so that there was simultaneously an orifice and a protruberance.

He said it was a sophistication test. The unsophisticated simply saw a tortoise. The half-sophisticated saw various symbolisms of which they assumed he was unaware. The sophisticated saw a nice photograph of a tortoise.

XXXIV

When she got her MFA, at least I think it was then, he bought a stuffed pink dachshund sitting up vertically, with a mortar-board on his head and the University of Minnesota badge hanging from his neck. His fore-legs stuck out and were joined by a couple of small strips of fabric, so that he could hold things.

JF hung a sign there saying “I did my best,” and he was there to welcome her when she returned home. When she asked what his name was, JF said Vincent Van Dogh.

Vincent became a permanent resident on top of the radiator in the kitchen near the dining table. They talked to him and about him a good deal, and he acquired some jelly beans in a little sack on the end of a pencil, which he held like Dick Whittington going off to seek his fortune, also a copy of one of the Beatrix Potter books.

They enjoyed what they imagined to be the kinds of things that visitors to the apartment said about them later. JF remarked that Vincent was obviously a dog-substitute.

XXXV

C. loved, they both loved, a Beetle Bailey strip in which Zero makes a number of contorted faces in front of a mirror and finally asks Sarge, “Does the mouth go down or up for intelligence?”

C. put up on the wall of their Oakland Road bathroom beside the mirror a strip by the French cartoonist Claire Breteché which he showed her. A middle-aged husband and wife are on holiday in Provence and she grumbles during each of their activities: “J’ai mal aux jambes,” “J’ai mal au coeur, ” “J’ai mal à la tête,” etc, until finally he storms off to St Tropez and spends the night disco dancing with a dishy youngster. Final panel, the husband drooping on a stool and saying to the sexpot, “J’ai mal par tout” (“I hurt all over”).

A number of other strips went up on their walls over the years. There are five on the refrigerator door right now that she put there, from Peanuts, Hagar the Horrible, BC, and so on. I think the two of them did a fair amount of communicating by means of such paradigms.

XXXVI

He did not often make her laugh out loud, but he did when after an egregious Asiatic-Indian colleague had come over and spoken to them at a social function, he whispered to her, “He’s being played by Peter Sellers.”

The two of them spoke at various times of an occasion during one of the Minneapolis heat waves when they had gone with her old friend Jim Cherry to a suburban cinema that was air conditioned, and had seen a comedy featuring Terry Thomas, Peter Sellers, Peggy Mount, and others called Your Past Is Showing and spent the whole time in hysterical laughter.

It was Jim who at one of his parties said in passing to a medical friend who was carving the last pieces of meat off a chicken’s carcass, “Is that the cancer patient, doctor?” That too stayed as a family joke, though she remarked dryly during her final illness that it wasn’t one that she particularly wanted to hear now. There was often a fair amount of giggling when they were with Jim.

XXXVII

Both of them loved naughty jokes (“What is yellow and black and screams when it rolls over?” “A school bus.”)

When they were with Bruno and Molly Bobak in the good years, there was a lot of joke-telling, just as there was for awhile with their friend Josslyn Grassby, who had been a student of JF’s and for several years was off teaching and doing Peace-Corps-type work in what used to be called the Far East. There came a time when the supply of jokes dried up, as if humour had become out of place in the real, the serious world of the Eighties.

Part of what drew them and Joyce Stevenson together was that Joyce loved jokes, had a fine supply of them, and was utterly unworried about whether or not she was politically correct. She is currently collecting blonde jokes (“How do you make a blonde’s eyes light up?” “Shine a flashlight in her ear.”)

When C. saw a photograph in Newsweek of a wide-eyed orangutan, she remarked that it looked like a just-arrived Peace Corps worker (“What, no indoor plumbing?”). If she came into a room at home where modern-modern music happened to be on the radio because JF had forgotten to turn it off, she would ritually remark, “Is the radio broken again?”

When she was acting director of the Dalhousie art gallery at the time of the Jonestown massacre and some group of women was wondering what to serve at a social function, she blandly suggested Cool Aid. She reported wryly that the suggestion was received with total silence.

XXXVIII

One of the things that made Halifax more endurable for them when they first arrived was Max Ferguson’s brilliant Old Rawhide programme on CBC radio. They listened to this every weekday at supper time.

I think that for them it was an epitome of what comedy should be, and also a heartening demonstration of Canadian possibilities.

It was a bravura half-hour, in which Ferguson—though for them he was Old Rawhide— played records and talked about or with a variety of characters, among them Granny someone who made jellied gin, Maurice Merrivale, the archetypal plummy-voiced politician (or was it political commentator?), and the actual news commentator James Bannerman. There was something called the James Bannerman doll—you pulled out its tongue and as it wound back in, some kind of pompous statement was made.

All the voices were done by Ferguson, who obviously enjoyed tweaking the noses of the CBC brass. The characters felt very real; they weren’t simply grotesques. The show was impeccably crafted but always felt relaxed. And Ferguson’s invention never flagged.

Eventually he got tired of the show, gave it up, and returned some years later with the Max Ferguson Show. But it wasn’t the same. For JF and I’m pretty sure for C. the Rawhide show displayed a free-spirited inventiveness, inside a corporation but not controlled by it, that could be tart-tongued at times, but was never egotistical or malicious and did not demean people. It was solid humour, humanly solid.

Some years later they were happy when there was a CBC strike and the suppertime period was filled in with old British radio programmes, such as My Word and Hancock’s Half Hour. When they were in Toronto for a few days in 1990, JF bought a Hancock record for her.

She adored Tom Lehrer and on a number of occasions played some of his numbers for dinner guests.

XXXIX

It has occurred to me that one reason why I have trouble recalling interesting conversations between the two of them may be that often they simply talked about things more or less in front of them, or recalled places where they had been, or speculated about places where they might go in future.

They could be simply in particular situations together—in a Paris gallery, on a Nova Scotia beach, driving through a high-altitude Mexican landscape, visiting the London Zoo—and commenting on what they were seeing, making them more real for each other. Being together in this way could be a very happy experience.

XL

In the first Modesty Blaise book, Willy Garvin, who has gone adventuring on his own, is in a Latin-American prison and due to be shot soon.

His mind has gone blank and he lies there greyly, unable to come up with any plan of escape. “He felt sickened by himself, but there was nothing to be done now because the light had gone out and the wheels in his head had stopped turning.”

Modesty has heard of his plight and breaks into the prison and comes to his cell.

There was no instant of delay in recognition. Willie Garvin sat up unhurriedly, swung his feet to the ground, and walked quietly to the door. In that time, smoothly and quite undramatically, the light in his head was there again and the wheels were turning. The recent past fell away like a fading dream.

C. could have that effect on JF.

He still remembers the time in 1957 when he had had to go from Minneapolis to Montreal ahead of her, and he met her bus with a hangover after he had been in one or two of the Ste. Catherine strip-joints the night before, and suddenly, when he saw her coming down the steps of the bus, and smiling quizzically at him, everything snapped back into focus and he felt real and centered again, and they went on to enjoy their overnight stay in Montreal before boarding the Cunard ship Sylvania or Ivernia for England.

Knowing that she was in the studio working steadily at a high pitch made it easier for him to commit himself wholeheartedly to his own critical writings. She once called him, in print, her muse. She was his.

XLI

He complained about her appearance from time to time, and she cut off her pony-tail to please him, not long after they were married. But he didn’t demand that she wear make-up, or high heels, or get her hair done at a beauty parlour. The two of them cut it between them.

The Couple I, 1969–70, oil