Mother and Daughter, ca 1959. Photo JF.

Morality

I

She held guilt at bay—disliked it. I mean, disliked an issueless brooding over things that one had done wrong in the past, and an issueless, self-indulgent talking about it. I don’t recall her ever asking me whether she had been wrong to do something, or seeking assurance from me that she hadn’t in fact done wrong. Equally I don’t recall her ever trying to get from me an admission that I had done wrong in some way.

During our quotation-marks courtship I was briefly engaged at one point in one of those terrible accusatory/self-exculpatory correspondences, the kind in which one’s whole being feels threatened by something that someone else has said, and the only alternative to surrendering permanently the high moral ground seems be to counter-attack. I wrote one of those long intricate letters in which one goes over what had happened, explains why one was not in fact so deeply in the wrong, and points out how the other person’s conduct was by no means as exemplary as he (in this case it was a he) seems to be claiming. It was a letter that I had to write, because the rupture of that friendship had been traumatic for me at the time and left me feeling a moral ruin.

I was pretty pleased with the letter. I felt that it reestablished me—or perhaps simply established me—as a moralist, in that period of Jamesian/Trillingesque moralizing. And I showed it to her hoping for her endorsement. She said very little, as I recall. She must have agreed that I should send it if I felt so strongly about the matter. But I’m sure she felt that all this was excessive, particularly since the original cause of the rupture had been so small.

At some point that spring or summer, she said something to the effect that I was arrested at Kierkegaard’s ethical stage. It may have been that that sent me to the Anchor Book volume of Fear and Trembling and The Sickness unto Death, and, more importantly, to Either/Or. It was during that spring/summer too that she remarked that Englishmen (or was it the English?) have no souls.

She was of course a moralist herself, but in more complex ways. She had, I am sure, reached Kierkegaard’s religious stage in various ways.

II

Some things didn’t bother her. She wasn’t, to my surprise, disturbed when I turned up on one occasion at the Oak Street apartment and confessed that I had been reading a violent thriller.

Capital-letter sex didn’t bother her as a zone of guilt. I mean, the mere physical aspects weren’t charged with an aura of guilt or naughtiness or sin. Nor was she afraid of men as potential sexual aggressors. She recalled amusedly how when a young man had attacked her on a street at night, she gave him a bloody nose and made him cry, and afterwards took him to her apartment and gave him a cup of coffee.

She spoke of having been to Fasching parties in Germany, though I realized later that she couldn’t have slept with anyone herself. She had been taken to the Reeperbahn district (Pauli?) in Hamburg, and when on our trip through Europe the summer after our marriage I wanted to go there when she spoke of it, she negotiated with a taxi-driver to find out where it was (she’d forgotten the name but remembered nude women), and we went there, and visited two or three of the clubs, in one of which nude women were indeed walking around among the customers, and watched a blue movie.

When we were on Pampelone Beach at St. Tropez in 1964 and I wanted to go in search of what I had heard was a section where there was nudity, she walked along with me and removed her own swimsuit casually, just as the following year, when we went to a lake near Halifax that I have returned to many times since, and where we had passed one or two people on our walk along the shore, she unfussily removed her swimsuit and walked into the water and lay naked afterwards with me on the smooth granite rocks. without casting apprehensive glances to see if anyone was coming.

One of the MFA students in Minneapolis was heavily and overtly lesbian. C., who I suspect she had tried to put the make on, was good-humouredly amused by her. She was comfortable with gays, and enjoyed gay bitchiness. When an old friend came out of the closet in the Sixties, she was comfortable with him and his partner in the house they bought in Minneapolis and lovingly decorated. She cared about them both, and was sorry when things started going wrong between them.

She was unbothered by the transsexual woman artist whom she met in Newfoundland, and whom she referred to in a natural way as “she.” She was sympathetic towards gently deviant figures in movies, like the foot-fetishist uncle in Buñuel’s Viridiana and the sensitive and withdrawn voyeur in the Australian movie Man of Flowers, a movie that she particularly liked.

III

But if she wasn’t conventionally “moral” (she had no trouble with smuggling things through Customs whereas I had guilt written all over me), she was very seriously moral.

Especially, though she didn’t talk about it in those terms, she believed in commitment. Probably the most important thing that I picked up from the reading that I did during our courtship was the Kierkegaardian idea of an existential commitment.

Kierkegaard mattered a lot to me at that time, along with Spinoza, in whom I took a graduate seminar as part of my Philosophy minor. She never told me to read Kierkegaard, or read anyone for that matter. But I read him, and one or two books by Tillich and Buber, hoping to please and surprise her. And if reading Lawrence had contributed to my not marrying someone else earlier, Kierkegaard and his analyses of attitudes that I recognized all too well in myself contributed, perhaps decisively, to my marrying C.

I think I can fairly say that I made an existential commitment then. I am quite sure that she herself did. And as I said, she cared about commitment in general, at least where it mattered.

I think she felt that people should be aware of doing wrong or being wrong, and their complacent obliviousness to this angered her. She was infuriated by the seemingly jaunty ignoring of common financial decencies by one gallery director who went junketing off on public money. She was exasperated by the apparent self-complacency of another young gallery director, blithely unaware of the extent of her own vast ignorance of art. But this was more a matter of wanting them to mend their ways in general.

She hated what might be called generic irresponsibility and uncaringness.

She was deeply angry, though I’m sure she didn’t express this to them, with two persons to whom we rented our house for a nominal sum during a sabbatical, on the understanding that they would take care of our two old cats. She was furious, after we had returned, to find saucepans burned, kitchen glassware broken, things simply missing—signs of a general slipshodness and indifference to the physical belongings of others.

She was even angrier, though she virtually never talked about it, with the disclosure by the vet that Annie, whose teeth were bad, had been given hard food to eat and had so wasted away that she went into spasms. She was also, I am sure, morally certain that Annie had been left out in the cold at times.

IV

She disliked people who “used” other people, especially ones who used her. The trouble was that she could almost never bring herself to refuse demands on her, at least if she felt that there was some moral obligation on her part. In the late Fifties she did a set of Chagallesque monotypes to illustrate a book of African folk tales put together by a former teacher of hers at Gustavus Adolphus College. She ended up having to design the whole book, for no extra money. She did work for me, such as laboriously spray-painting a bamboo screen to separate the dining and living rooms, that I shouldn’t have asked for. The spray paint probably hurt her lungs.

Later she and a couple of other friends, Betty Moore and Lesley Armstrong, put a great deal of work into preparing for the Friends of the Public Gardens an illustrated booklet on the Halifax Public Gardens, as part of the campaign against an impending high-rise, but also as a service to the Gardens themselves. She couldn’t bear to see things done incompetently or with only a partial commitment.

V

She disliked a certain kind of egoism in promoting one’s own career. She had no objection to the kind of artist who supported his family with his work and competed for commissions. But she disliked the way in which one or two married women artists appeared to live and breathe in terms of their career advancement, and was quite angry when she learned of how an intelligent academic woman had accepted a position that would take her away from her very nice husband for two years. C. said flatly to me that she could simply not conceive of doing that to someone whom one cared for. She was absolute about that. We did not know the whole story, though.

Contrariwise, she made no effort to persuade me, in her own interest, not to apply for the prestigious co-editorship of the Southern Review in Baton Rouge when I was invited in the early Eighties to do so, even though accepting it would have entailed uprooting her from all her friends and acquaintances and moving to a climate that would have been terrible for her health. (I did not in fact apply.) Loyalty was a major value for her.

VI

That was partly why she so much valued the all-too-brief friendship with Joyce Stevenson that she enjoyed during the year before we went away to Mexico for our final sabbatical and after our return.

Joyce, a dark-haired, youthful-looking woman in her late thirties, was married to a very bright man working in the museum conservation department of the federal government—a superb furniture-maker, and very knowledgeable about computers. They had been highschool sweethearts (if that isn’t too icky a term), they had married shortly afterwards, and the marriage was obviously as permanent as the mating of swans. That, I know, pleased Carol. She hated it when marriages broke up.

VII

They were a remarkable couple. Joyce herself was very intelligent, though she didn’t have a college degree. (Neither of them did.) She was also very strong—or knew how to use her body well—and very good with her hands. The two of them were a bit like Modesty Blaise and Willy Garvin, in that one kept being surprised by the things that they had done. Joyce who at the time when I write is very efficiently managing a semi-arty bookstore, had been at one point the only woman in a construction crew. At another time the two of them were working at an open-pit mine up in icy Northern Manitoba, where Joyce among other things operated some huge piece of ore-crushing machinery. One would never gather these things from looking at her.

C. was grateful for her strength and competence: Joyce built her, for money, a fine large nest of shelves that enabled C. to bring order into her studio, and worked enthusiastically from time to time in C.’s garden. Like C. she was a craftsman and detested half-assed work.

Like C., too, she was congenitally irreverent towards authorities and loved politically incorrect jokes, of which she knew a lot. She was funny, she had an enquiring mind, and one could have comfortable wide-ranging conversations with her, as well as simply sitting quietly together. She also seemed to me almost always sound in her judgments and opinions, like C. herself. I never remember her saying a dumb thing.

But the vital thing was that she was entirely honest, so that you always knew that she meant what she said and said what she meant, and was entirely without any desire to play self-promoting or self-defensive mind-games. Moreover, if she promised to do something, you knew that she would do it.

She admired C. immensely, and her friendship mattered a great deal to C. Here was someone in whom C. could repose complete trust, and with whom she didn’t have to keep watching her back or worrying about some psychological mine-field into which she might unwittingly intrude. She was also unabashedly a gardener and a cat-lover, in C.’s kind of way. I think that she was the ideal daughter that C. would like to have had.

VIII

C. hated cruelty to animals. On one occasion in Tepoztlán we went to a miniature rodeo, where the spectators stood casually around an ad hoc corral. A large Brahmin bull was roped and fell heavily. She simply ran from the scene, and I’m glad that I had the grace to follow her. I’m also glad that I never expressed or had any interest in seeing a bullfight, let alone trying to persuade her (on the basis of Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon) that bullfights had to be understood as parts of the cultures in which they occurred, that there was something heroic about them, etc.

In the acknowledgments at the start of the catalogue to her great 1977 exhibition, I came upon a reference to myself as her muse. When I expressed surprise at this, she said something about my being someone who wept—as I had—over the death of a lame squirrel on the University of Minnesota campus whom we had befriended, along with her companion, and fed with peanuts during a particularly hard winter, and who ultimately (she having been driven out of the nest when a third squirrel moved in, and bitten on the bad leg so that I would see her moving increasingly slowly and painfully) I found one day lying stiff and cold, her nose pointing towards the base of the nearby tree where she herself now lived.

IX

She cared very deeply, as did I, for the wonderful old skinny cat, one-eyed, his teeth worn down, his hair thin, his ears ragged, whom the couple we shared “our” Provençal house with during our first summer in Seillons-Source-d’Argens (1964) nicknamed Raghead. He lived in the lane outside the house, and had been fed after a fashion by the goodhearted woman who lived next door, but without becoming “her” cat. We fed him, but he couldn’t come in the house after a woman friend joined us who was allergic to cats.

When we returned two summers later on our own, and went for our first stroll up the lane, we passed what looked like a small bundle of rags or some small dead thing in the grass. C. cried, “It’s Raghead,” and when she crouched down beside the body, it stirred, and Raghead climbed immediately up into her lap, and then followed us up the lane, staggering, and afterwards back into the house where for the rest of the summer we gave him the home that he obviously craved.

By this time he was sick in the chest, and the eggs that flies laid around his empty eye-socket hatched out into maggots that lived in the socket and that we had to wash out or gently extract.

One night we talked in his presence about what would become of him after we left, and speculated about taking him to a vet in nearby St. Maximin to be put to sleep. He declined to sleep inside the house that night—the only occasion, she insisted, when he did so. On the night before we were to leave, we invited the next-door neighbours in for the first time, Monsieur and Madame Bornens, and he came in and immediately climbed up into the lap of their very nice teenage daughter Evelyn. He was a remarkable animal.

After we left and abandoned him for the second time, he was apparently taken in by Madame Bornens, because she wrote to us that winter, or Evelyn did, that he had died beside the fire despite the various delicacies that had been offered him.

X

C. valued him deeply. I think he was an emblem for her of gallant, sensitive, and intelligent endurance: a significant consciousness. She spoke of him often later, telling other people about him.

She loved his delicacy in the mornings during our first summer when he would quietly go down to drink from the wet spot below a public tap in the wall below our house, and sit for a bit and quietly watch the other cats being busy, and then stroll back up into our garden. She was amused by how, when one day he was lying in the shade in the garden and she offered him a plate of liver, he got up so fast that he fell over.

She was intensely conscious of his having been abandoned by his original owners, and of his manifest craving for a home again after his years of homelessness, handicapped by having had his eye knocked out by a slingshot. He became linked in her mind with Mr. Dickenson, the courteous and unselfpitying town drunk in Arthur Upfield’s Australian detective novel The Widows of Broome, reduced at times to drinking drops of battery acid in water, but never losing his dignity.

Sentimentality? I don’t think so.

She also regarded highly the small, wiry old Seillons woman, Madame Robert, who washed our heavy linen sheets down at the roofed-over public tank. She worried about friends’ health (so-and-so was much too thin). She made a point of visiting from time to time an older woman friend who was suffering from Alzheimer’s, and an old woman artist, Grace Keddy, who was stoically and gracefully living with very painful arthritis in a to me very depressing nursing home. She persuaded the Dalhousie Art Gallery to give her a small one-woman show, her first serious recognition, and wrote the introduction to the small catalogue.

XI

She was angry—I thought a bit unreasonably—over housepainters or tree people who trampled on flowers, simply not “seeing” them or not feeling that flowers mattered. She was angry at the developers and aldermen and consortium of greedy doctors who together were bent on putting up the monstrous high-rise that would tower over the lovely Halifax Public Gardens. She put two or three years of very hard work into the efforts by a small group, the Friends of the Public Gardens, to block the project. They lost in the end, and perhaps they were doomed to lose, but it was a brave fight, largely by women.

She herself took the most scrupulous care of the houses that we rented in Provence and Mexico.

XII

She had things to feel remorse about. Or if not quite that, images of the unhappinesses of others, in which she was in some way implicated, and which could have played and replayed in the theatre of her mind had she let them. I have already mentioned her knowledge of what Annie must have gone through at the hands of persons in whom C. had put trust—an old cat, stiff in the hips, hungry, out in the cold.

Moreover, earlier C. herself had had to treat Annie cruelly when her asthma compelled us to banish the three cats from our bedroom. Prior to that, it had been a nightly ritual, Annie coming to the head of the bed to look up at C., then going to the foot and climbing up onto the bed and making her way to the head, where she lay beside C.

They were very close. Annie made C. her person, and it was C. who had brought Annie up into our Queen Street apartment, a small scruffy white waif whom she had found holding off two or three dogs in one of the streets in which C. searched for our beautiful, long-legged stand-offish Amy after she went missing because C. had let her out when her crying and writhing in heat became intolerable.

Another mistake, that, and we never did find out what happened to Amy, wandering and homeless.

XIII

During our second summer in Provence, C.’s mother was sick with a recurrence of her cancer, and C. knew it, I think, when we set off for our three months there in Seillons.

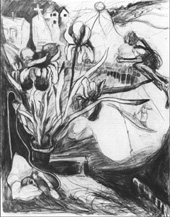

At the end of our stay, she had to leave a few days before me, heading directly for Minneapolis where her mother lay in the Lutheran Brotherhood hospital. Her mother died not long after. I do not know how much pain she was in, but I am pretty sure that she was in pain, and that the morphine alluded to in the drawing Mother’s Morphine Dreams ceased being fully effective, possibly because at that time they knew less about dosing against pain.

Hazel Hoorn had not had an easy life. She suffered from sinus troubles, as C. came to realize later, and I think migraines, and would have loved, she said, to live in the American Southwest, but she had to pass her married life in Superior, Wisconsin, among what to her were strangers. As a child she had had another exile, being separated from her twin when they and a third sister were given out for adoption. After C.’s father died in the early Forties, leaving them more or less penniless, she had to go back to school-teaching, an occupation which she did not enjoy, and taught home economics.

She was attacked by cancer in the early Fifties, had a breast removed, was given radiation treatment and a prognosis of only a few months, and survived for fifteen more years. (I may not have these figures right.) At some point Carol had to resist the idea of their setting up house together more or less permanently. It would not have worked out, I am quite sure of that. But it had apparently not been easy for her to say no.

XIV

When I knew her, Mrs. Hoorn was living in her own small one-storey house in Pine City, a small community north of Minneapolis. I think that she was proud of it and very pleased with it—that it was the kind of house that exactly suited her, and one that she had bought herself out of her own earnings. She was a lady, and very nice in her basically shy way. She had a very nice sense of humour and could laugh at herself at times.

But she could also be brusque, and she had been tough enough to stand up to C.’s formidable Aunt Molly and make her way as the non-Lutheran wife who stole the Reverend Hoorn away from all the hopeful young ladies. “Does he [meaning me] really have to escape that much?” she enquired of C. when C. showed her the mound of my paperback thrillers in our living-room closet? She also, while we were, to use that incongruous term again, courting, dreamed of two white eagles, which seemed to me an important omen or sign, and which heartened me to go forward to marriage. She had done some work in pastels when she was young. C. hung three of her pieces on our Oakland Road walls.

XV

When we went to Seillons that second summer, C. did not mention to me that her mother was sick. I think she made an existential decision not to spoil my/our much-looked-forward-to Provence vacation, especially since the prognosis may not have been all that definite. She was probably also influenced by the fact that in 1951, when she was having her very important time in Germany, she returned to Minneapolis in response to a peremptory summons from another relative, and did no good to either her mother or herself by doing so.

But it cannot have been easy, and in retrospect it must have been painful to contemplate her mother slowly dying in Minneapolis while we were enjoying the blessings of Provence, including the visit of the Bobaks.

As I said above, though, she didn’t talk about these matters with me. and she didn’t allow them to dominate her. She was tough-minded enough, I suspect, to work out for herself that what happened with Annie was effectively out of her control, and that no good purpose would have been served by hanging around Minneapolis for three summer months.

For that matter, her mother may herself have urged her not to do so. Her mother was very pleased when we married, she seemed to like me (partly because I was English and not, not, Swedish), and she obviously wanted us to be happy. She was the most unintrusive and undemanding of mothers-in-law.

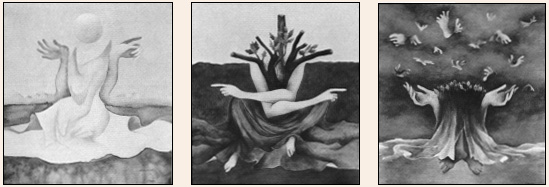

After her death, C. drew “Mother’s Morphine Dreams,” and began the shift away from realism.

XVI

She did speak about one thing about which she felt guilty, and the feeling made her angry. She said bitterly at various times that she felt—or was made to feel—guilty about not being out in the studio working. It was I who made her feel that, at least early on when she lost herself in her garden for days at a time, and later when she sat and watched a lot of TV during the day.

XVII

I suspect she also reproached herself in connection with the death from a heart-attack in 1982 of our friend Claude Besnault.

Claude was a remarkable Frenchwoman a year or two older than myself, whom we met during our first stay in Tepoztlán, where she was living. She was very good looking, with that bell of straight, black hair, cut level all the way around that one sometimes sees in French movies from that period. She came of a good upper-bourgeois family. Her father had been a civil engineer, and she may have been born in the Middle East or North Africa, where he worked. Her brother, whom she despised, eventually became an admiral. She was taught in a convent school. After the Liberation, at the age of eighteen, she received the Croix de Guerre for having served as a courier for the Resistance.

In the immediate post-war years, she became one of the group of obsessed young movie goers at the Cinématheque that included Truffault and Godard. She married a cameraman and they had a son. After they separated, she worked at one point as an extra, or was it a nude? at the Grand Guignol. She studied mime under Marcel Marceau. She wrote a novel about a girl in wartime France that was published by Gallimard in 1959, Une Jeune Femme.

At some point she became Buñuel’s mistress, and the novel is dedicated to him. There was a wonderful point in one of our conversations when C. or I said something critical of Viridiana and she said, unaffectedly, that she found it hard to judge because she had seen it with Buñuel. She had known a number of people who mattered, among them Jack Lord who later became the Minister of Culture. She had a low opinion of almost all of them.

XVIII

When Buñuel moved to Mexico, she followed him, but by the time we knew her the relationship had come to an end. She had written a book about Mexico, she did occasional pieces of journalism, she had other projects. She lived in a simple but comfortable adobe house that she rented, for fairly little, along with her family of a dozen or more cats.

She spent a fair amount of time in conversation worrying about her son, who was still in France, and being vindictive about her mother, and concerned about her inheritance, her mother having recently died. She was egotistical, but knew it, and drew us entertainingly into the drama of her life. She hated the Church, the Army, male-chauvinist pigs, particularly ones who assumed that she would be easy to seduce. She recalled telling one of them, at the end of a brief affair, “I am a test and you have failed it.” She was a classic French rebel.

She was also the most generous person I have ever known, concerning herself a lot with the well-being of her Mexican village neighbours, with whom she appeared to be on very good terms, and with refugees from Guatemala and the like. When she received her inheritance, a fairly substantial sum, she spent it, so far as we could gather, largely on others.

We stayed with her one Christmas, and in 1973, after she had moved to an apartment in Mexico City, where she worked in the French bookstore, she spent a week or two with us when we were vacationing at Zihuatenejo, north of Acapulco, that she had recommended to us. She loved being comfortable at times, she was an excellent and undemanding guest, and she very much liked Carol. She had several friends in Tepoztlán and Mexico City who cared a good deal about her and gave her money, as did we, without any embarrassment on either side.

XIX

When we returned to Tepoztlán in 1981 and sought her out in the nearby village where we heard she was living, we found her in a two-room adobe house, with no running water and no toilet, not even an outdoor one. She was unhealthily puffy, and had lost a couple of teeth. She had also recently lost her bookstore job because she lipped off at the French official in charge of the Alliance Française.

She was supporting herself and her animals—there were now about fifteen cats, all with names and characters, Old Mama, etc., and three dogs—by teaching French in a language school in nearby Cuernavaca. But after she sued the Alliance Française for wrongful dismissal and won, she was blacklisted from any teaching jobs.

We brought her sacks of food for the animals. We picked her up on weekends and brought her home with us for the day, where she showered, and doused herself extravagantly with body lotion, and dyed her hair, which Carol cut from time to time, and ate a lot, and lay soaking up the sun in our very comfortable chaise longue. She said she was une vieille cocotte. She said to C., whom she persuaded to dye her own hair, “We must stroogle.” She was still quite fearless. She reminded me of Mehitabel in Archy and Mehitabel—“Toujours gai, little Archie, toujours gai.” C. also gave her money from time to time, but with the awareness that it would be spent extravagantly.

She spoke of going back to Paris to live, and hoped to benefit from having known the present culture minister, Jack Lord. Both of us felt that she was now a good deal out of touch with the new France, and would be something of a Rip Van Winkle were she in fact to be offered anything by Lord, which we doubted.

She had her missing teeth replaced by a dentist whom I think she slightly conned. She took medicine for her heart condition. She kept herself impeccably clean despite her living conditions. She gave me one of her handful of books on the shelf above her bed.

XX

She and C. talked a lot together. She was very quick and acute psychologically, and C. could probably say things to her that she couldn’t say to anyone else. C. worried a lot about her. Claude was, in her way, C.’s project now, as Raghead had been in Seillons, and C., who enjoyed her company, obviously partly felt towards her as she had felt towards Raghead, though at times she was exasperated by her improvidence and by the feeling that there was little that could be done to help her, short of a very large windfall.

XXI

The winter after we returned to Halifax, we learned from our friend the linguist Karen Dakin that she had died suddenly of a heart attack in the car of a friend who was taking her to a clinic.

It shocked C. deeply, and one of the things that she said to me was that Claude almost certainly died because she had stopped taking the medicine for her heart, and that she had stopped taking it because she could not afford it. C. probably lived for a good while with the feeling that if only we had given her more money Claude would still be alive, or that some way or other could have been found to ensure that she was given the medicine. It was a bit like Annie again. She may have been able to tell herself intellectually that there was probably in fact nothing that could have been done, given Claude’s nature. But I don’t suppose that that settled the matter, since she could have been wrong.

When Claude died, something important went out of her life—a gallant fellow rebel who knew that life was not a simple matter, and who I think valued C. herself highly, for the right reasons. I suspect that being accorded Claude’s friendship and esteem helped to confirm her in some way in her own far from simple identity. Claude was sophisticated and untamed—untamed like Lawrence’s golden Sicilian snake in the poem of that name, or like the big cats that C. so much liked to watch in TV nature documentaries. Almost everyone she knew in Halifax was unsophisticated and tamed.

XXII

I would say that for C. the three deadliest sins were cruelty, greed, and disloyalty. One of her complaints about young or youngish people, for awhile, was that they seemed to have no sense of loyalty to individuals or institutions.