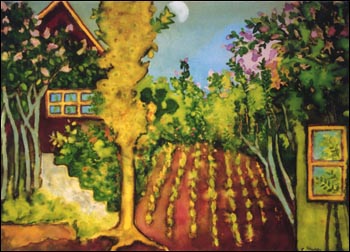

New Planting, ca 1989, w.c.

Sacralization

I

I’m not sure I’ve got the right term, but it’s what comes to mind immediately when I think of the first years of our marriage.

She worked so hard at making things work—at making a marriage. She wasn’t, I would think, naturally a marrying person—certainly not someone who naturally looked forward to giving up her freedom, tying her fate to someone else’s (where he goes, she goes), having and raising a family. But once married, she did everything, I would say, with that quality which (by referring me to Kierkegaard) she had made so important for me, namely ultimate concern.

She liked, she insisted on, small rituals. There had to be the good morning kiss, the coming-home kiss. Saint Valentine’s cards were imperative (homemade by her and, in those days, by me). During the previous few days she would drop reminder-hints as to what day it was next Tuesday, did I know? I usually pretended I didn’t, but I think there were very few times during our thirty-five years when the day went uncelebrated.

Meals were regular. I think they were there for her as fixed points in the day, not as things to be adjusted to the flowings of her creative energies. I doubt that I ever came home from work to find her absorbed in the studio oblivious to the passing of time, and with supper late. I’m certain I was never asked or told to fix something for myself. When I told her about Shrove Tuesday in England, pancakes with lemon and sugar became part of the year, part of Pancake Day. She always checked me in the morning to see that I was properly dressed, and kissed me goodbye (another absolute). I don’t know how much cooking she did before we were married, but we normally ate cheaply but satisfyingly, and when we had company to dinner, it was always—so far as food was concerned—a pleasant occasion. She became in Halifax a superb cook.

II

A small paradigm. She needed a kitchen spoon and carved one for herself, beautifully moulded to the hand. I wish we still had it. I remember thinking of that Latin saying about someone’s touching nothing that he didn’t adorn.

I don’t know that she ever threw a pot or dish on a wheel—I mean, made one that she wanted to keep. But I knew her painting. And there was a lovely small bronze figure of a girl by her, and a fine strong plaster head of an old woman, and an etching or two, and two or three beautiful pieces of jewelry. One of the very few photographs that she took during our first trip to Europe, when printed for us by a friend, was accepted for exhibition at the summer State Fair. She became an excellent photographic printer herself later, and printed my photo of herself and her mother.

She made certain dresses, particularly a wrap-around red paisley, that I loved and that she wore until they fell apart. She made our Christmas cards with lino-cuts, and made the Valentine Day cards and Christmas and birthday cards for me, and wrapped presents lovingly. Years later, in Halifax, she made two or three glorious patchwork covers for cushions—thick, rich, glowing.

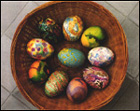

Another ritual—dyeing Easter eggs.

We did it every year at the kitchen table, and continued doing it in Halifax, and I have a sizeable cardboard box now containing the best of them, and some of them—about thirty-five, a symbolic number, the years of our marriage —seem to me beautiful and inventive. She loved trying new techniques, and I followed her in that, and each of us learned at times from the other, without intellectualizing it. I can tell for the most part which eggs were done by whom, but there are a few which could have been by either of us.

In Halifax, after we moved out of our third-floor apartment on Queen Street where things were hard for cats, she took such good care of our cats that four of them lived to be sixteen or seventeen.

III

On Oakland Road, she became a gardener.

It took me a good while to realize how important the garden was for her, and probably I still don’t. Certainly I begrudged for a good while the time and effort that she expended on it. I thought that this was not what being an artist was all about. It was very alien to me, and she was very distant from me, in a space of her own where I couldn’t or wouldn’t follow her.

Even now I can’t judge how good a garden it is, and she always complained about how unsatisfactory it was, and often felt unwell or was in physical pain after working in it. But friends have praised it, and it seems a very pleasant garden, in a free-form way.

When we enlarged our house in 1982–83, at the time when we had to have the outer walls taken off so that the poisonous foam insulation could be removed, she did the designing. The large appended sun-room, plus storage room plus washroom plus wide corridor lit by a skylight, is very satisfying—comely proportions, lots of light, very serviceable space.

IV

All these things that I have been talking about were done unostentatiously and uncompetitively. Moreover, if she believed in doing things well and with commitment, she didn’t fuss about always having the best equipment for the job—didn’t keep reaching after perfection there.

She bought certain pieces of studio equipment, such as an adjustable drawing table and a magnifying glass on an arm, and she had some daylight-like fluorescent lights put in. But she bought them after she had put up with a good deal of discomfort because of not having them, just as she lived for a good while with a too-stiff stapler for fastening canvasses to stretchers, and with a plainly defective sewing-machine.

She never had an easel, at least after she moved out from her M.F.A. studio. She tacked unstretched canvasses on the wall, and hung stretched ones on nails. She never had any decent chisels. I’m not sure she even had a mitre-box for making 45 degree angles when building stretchers. The tool drawer in our kitchen was a mess, the tines on her garden forks stuck out at various angles.

She was not afraid to spend money when something was essential. She was pleased with the macro lens that she used for making slides to illustrate her public lectures with. She bought a good stove and a good washing machine after the ones that we had acquired with the house finally broke down after fifteen or twenty years.

But she had no desire for a microwave oven. And she was very impatient about shopping around so as to get the best deal on something or make sure she’d bought the best product in the Consumers’ Research sense. She bought in haste on several occasions and did a lot of grumbling subsequently.

V

She also refused to worry at times when something was less than perfect. Personally I thought that the stereo system that we bought in 1984 when our second-hand hi-fi machine finally broke down sounded a bit thin and dry. But she refused to get involved in talking about it, and was quite cross when I occasionally brought up the matter.

Nor was she concerned about our getting the perfect performances of this or that work. She said she wanted to enjoy music, not have to fret about it. She was scornful, as was I, when friends informed us that we must, absolutely must, get into compact discs. Our LP’s, some of them fairly old, were quite good enough for her. She played some of them over and over in her studio on a cheap portable, and made and played tapes of others.

If she hated wasting anything—wasting food, throwing away something before it was worn out, junking something that one had recently bought—it wasn’t because of meanness. It was because, or so I judge, doing so displayed an unvaluing attitude towards things, a feeling that they could be casually discarded.

She hated throwing clothes and fabrics away, and complained from time to time about this attitude of hers. But I know what was involved. I know that, when contemplating a specific dress or blouse, as distinct from looking at a row of them and recognizing intellectually that there were too many and that she never wore some of them, she could not bring herself to throw this particular created thing, still charged with merit, into the trash can and annihilate it.

VI

Our friend Anne Higgins spoke recently [1991] of how C. ate—concentrating on her food, focussing on it, attending to it; eating, she said, “in the present tense. “ She recalled with pleasure watching her eat an avocado in Ajijic. She said there was nothing compulsive or ostentatious about it. Simply, at that point, eating what was what C. was doing, and as with other things, she gave it her full attention. These were unsolicited and unprompted remarks.

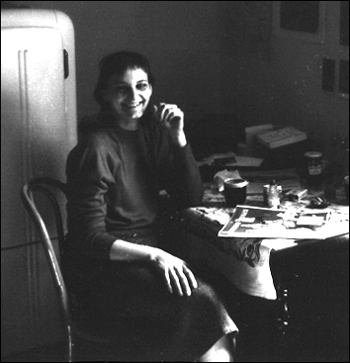

ca 1957. Photo JF.