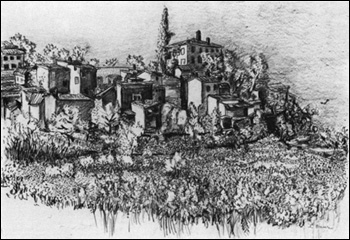

The Village of Seillons, 1966, pencil

Seillons

I

In 1964 we rented a house in Seillons-Source-d’Argens, a hill village about twenty-five miles east of Aix-en-Provence and forty from Marseilles.

Actually, four of us rented it, the other two being Bill Bartsch, who graduated from the Minnesota MFA programme around the same time as C., and his friend and roommate, John Blue, who I think was in art education. C. and I found the house, Bill and John provided a white rented Simca, and we were going to split the costs down the middle. This was well before those books about the chumminess of Provence village life by Peter Mayle.

II

Provence had been the Great Good Place for me ever since as a teenager I read Ezra Pound on the region in his poems and essays and Ford Madox Ford’s volume of reminiscences Provence. Francis Beeding’s 1920s thriller The League of Discontent, set mainly near the Pont du Gard, may have done some imprinting earlier. I had hitchhiked in Provence for a few days in the summer of 1949, visiting Marseilles, Arles, Avignon, and the Pont du Gard.

In 1962, as C. recalls in an interview with Ian Lumsden, we had gone on a sort of Van Gogh pilgrimage—the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, the Kröller-Müller Museum twenty miles, or whatever, out in the country, and finally Arles and Saint-Rémy. We also spent three happy hedonistic days of what they called “the lizard life,” with our Australian friends Alan and Barbara Donagan, in their hotel in Ste. Maxime, across the bay from St. Tropez.

III

It was that summer that we discovered the garden in the former convent in the castle at Villeneuve-les-Avignons, a garden of gardens, and in a sense our own private garden, because no-one was there during the two or three hours that we spent in it, and no-one to whom we talked afterwards had ever heard of it.

She loved that garden, as did I.

The lower part was formal—box hedges, gravelled pathways, urns, statues of classical deities, an ornamental pond with lillies. (She hung a photo of mine later, a to my mind unsatisfyingly printed photo of a corn goddess smiling among trees, in our bedroom.)

And when you passed through a heavily vaulted tunnel or climbed some steps, it became wilder, a true Provençal zone of dry hot earth, and small terraces. and half-ruined walls, and cypresses, and olive trees, mounting upwards towards the high boundary wall at the top of the hill, and the almost always blue sky beyond that. The view from the garden was magnificent, or at least there was a magnificent feeling of being high up above things, and at times the mistral blew.

We returned to the garden in the Fort St. André every time we were in Provence, and it figures in at least three of her paintings. It was her garden paradise. It became a major emblem for her.

IV

In the spring of 1964, I pored over maps in our Queen Street apartment and studied the green Michelin guide to Provence. I remember settling on the area to which we in fact went, but have no idea how I did so. No doubt being reasonably near to the sea and St. Tropez had something to do with it. The Riviera would have been far too expensive. My sister Elizabeth, at that time working on an M.A. thesis on Malraux in Paris, put an ad for us in one of the Marseilles papers, we received perhaps four or five replies, and the one from Seillons was much the most attractive, as was the price.

The house was the family home of Monsieur Florens (strictly speaking Maître Florens), the chief judge in the regional assize court in Aix. He and his wife and children now lived in an apartment in Marseilles. He cared a lot for the village, where he had grown up, and wanted us to like it and be happy there. The clincher to his celebration of the charms of house and village was the information that you could see Mont St. Victoire from the upstairs balcony. He had all the appearance of being a decent man, and we agreed to take the house for June, July, and August.

V

The house and the village were charming, even if not possessing the kind of holiday ambience and elegance that Bill and John, who arrived a few days later, had obviously been looking forward to.

The house was not large, but it was quite large enough. Downstairs there was what I recall as a dark-brown dining room, which I appropriated for my own work when we weren’t occasionally eating supper in it. There was also a reasonable-sized kitchen, cool and very French, a bathroom with shower, a store-room, and a back door into the alley behind the house.

Upstairs there were three bedrooms in a row, the one in the middle very small. One of the larger rooms had a double-bed and we appropriated it, leaving the one with two beds for Bill and John. There were balconies in front of the two larger bedrooms, and you could indeed, on a clear day, make out the tip of Cezanne’s mountain from one of them. All the rooms in the house had shutters.

The greatest charm of the house was its location and its front yard.

It was one of a row of four houses that looked onto the village square. If you stood on the square and looked at the houses, the one on the far right was occupied by M. Florens’ aunt, “une vraie fleur de la Provence” as he called her, a stooped but still active old lady less then five feet high, who stayed indoors most of the time. Then came the house occupied by M. Gall, a small, shy, but obviously prosperous peasant, and his family. Then came ours, with in front of it the start of a short lane leading a piece of land owned by M. Florens.

Lastly there was the house of Monsieur and Madame Bornens and their daughter Evelyn, at that time probably about fourteen. Monsieur Bornens was a retired gendarme from Savoy, with a touch of Jean Gabin to his appearance, who spoke a clear slow French and was quite willing to have leisurely conversations with me. He was farming now, probably in a small way. His wife was energetic, handsome, probably from the village herself, and friendly to Carol. She looked after a sizeable garden attached to their house, and was fond of cats.

VI

As you came in through the gate of our house from the place, on your right there was a concrete laundry trough, a pump, and a small tree or two.

On your left was the real heart of the house for us, a slightly raised and gravel-covered area, with vines climbing up the wall on one side, a vine-covered arbour overhead in the part nearest the house, a circular outdoor table (concrete? metal?), a stand for a large sunshade, and a hedge running along the side overlooking the lane, preventing other people from looking in on us, but low enough so that if anything interesting seemed to be going on outside, we could stand up and look over the top. There was also a deck-chair which I appropriated during the day when the others were off jaunting or sketching. We ate breakfast and lunch at the table, on chairs that we brought out from the house.

The grocery, the bakery, the butcher’s, the tobacconist-cum-newspaper store, and the post office were all a couple of minutes away. The village cafe, Le Cercle des Ouvriers, was just below us on the square. A couple of times a week there was a small market on the square.

On the top of the hill there was a cemetery with magnificent cypresses, and a sizeable area of open ground that served as communal grazing land. The sides of the hill were covered with vineyards and fruit trees. Three roads led down to the road that circled the base, and then to St. Maximin, three-and-a half-miles away, and other parts. The village had streets on three different levels. There was always something new, if only a new perspective, to catch the eye, and always somewhere to walk to if one felt like walking.

Madame Robert, an energetic and friendly lady in her fifties or sixties, did our laundry for us, down at the village laundry place, a set of concrete troughs with a roof over them. There was also the company of the old homeless one-eyed cat Raghead (John Blue’s name, I think) that I talk about elsewhere.

VII

C. and I spent more time in and around the village than the other two, and loved it, but were glad to be chauffered around from time to time. The four of us made trips in the car to St. Maximin, to Aix, and, most importantly, to St. Tropez, which was pretty much what we had hoped for, particularly on the lovely long Pampelone Beach.

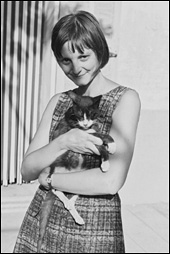

At one point my sister Elizabeth, still very much the charming kid sister, turned up for a few days, and Monsieur Florens invited the three of us out to lunch in Aix to meet his colleague Monsieur Audier and Monsieur Audier’s cool and elegant American wife. Monsieur Audier, as C. remarked on various occasions, was straight out of one of Daumier’s courtroom cartoons.

We had an enormous five-course lunch, in a back room in what had looked at first like a simple pizza joint, with at least a bottle of wine apiece. M. Florens paid the bill, which must have consumed most of what he got from us in the way of rent. Afterwards he drove us out to a field at the foot of Mont St. Victoire, where Madame Audier, C., and I collapsed and the other three staggered off into the woods to look, don’t ask me why, for fossilized dinosaur eggs.

In the late afternoon the Audiers drove the three of us, sodden with food and drink, out to Apt through a thunderstorm, where C. and Liz and I took a large room in a cheap hotel and passed out immediately on our respective beds. The following day, with the other two still asleep, I found myself in a surreal conversation with the proprietor, a huge ex-Legionnaire with a large scar on his massive head, as we sat at the bar in the semi-darkness—the storm had put out the lights—and watched the rain thundering down. When the others finally came down, he insisted on driving us to the north of Apt to look at some red earth.

From Apt we went by bus through Haute Provence to Giono’s Manosque, and fell asleep in the public gardens after emptying a large bottle of 15% Algerian wine between us. We were all younger then. The whole experience always stayed very sharp and accessible for C. and me—for Liz too, probably. I know that our minds met in that kind of experience—that we “saw” and recalled it verbally to others in the same way, without any contradictings and correctings.

VIII

C. loved Seillons. We both did. She loved the kinds of things that I’ve talked about; loved Raghead; loved our night-time walks around the village, usually past the cypresses of the cemetery; loved finding a praying mantis; loved it when I noticed a funny green protuberance from the overflow drain in our bedroom sink and it turned out to be the nose of a small green frog that had somehow climbed up the pipe on the inside.

One night a little family circus performed in the square, father, mother, a couple of kids, some performing dogs, maybe a pony. I forget which of them was upside down on a rope or pole, trapeze maybe, up among the plane trees, but it was pure Chagall.

IX

We rented the house for three months again in 1966, this time on our own. We didn’t have a car, and getting to the sea, at Hyères, by means of a village bus was something that we tried only once. At one point I got fed up during the three-day blow of a mistral and went off alone to Marseilles and thence to Le Lavandou and —bliss!—the Ile du Levant. But we had lovely times there on our own, both of us working steadily, and in that miraculous summer I wrote some of the best things that I’ve ever done, including the Atget essay and what was to become, in the Seventies, Violence in the Arts.

The high point was the week that Bruno and Molly Bobak spent with us.

We had been briefly introduced to each other that winter by Moncrieff Williamson in the basement of the Confederation Centre in Charlottetown. When they turned up in Seillons—they were driving around Europe—they thought they’d probably just spend the night and pass on. They stayed a week and it was pure pleasure all the time, whether we were sitting at the garden table telling jokes, or eating in a good cheap restaurant in St Maximin where Molly lost one of her contact lenses in the sauce américaine, or doing St. Tropez, or simply driving around in the lovely countryside near Seillons. Bruno was on his very best behaviour—interested in everything and wholly charming. A lot of sketching went on, and a lot of companionable drinking.

Figs and Olives, 1965–67, oil, gold leaf, gold paint