Torvill and Dean. Photo from International Figure Skating, by Christopher Navin.

Sports

I

She loved watching skating and gymnastics on the box.

We were closest in some ways when we watched skating competitions together and commented to each other about what was going on—how this routine had slack spots in it, how marvellously that triple was done, how a costume was too busy and broke up the lines of the figure, how we wished Toller Cranston would shut up at times and let us simply watch what was going on, how marvellous Torvill and Dean were in each new routine.

There was a whole cast of characters and types for us—for her even more than for me, for she watched every bit of skating that was on and had a better memory for names. Torvill and Dean, Brian Boitano, Katerina Witt, Brian Orser, Elizabeth Manley, Scott Hamilton, the French-Canadian brother and sister who skated for France, the tall long-legged British skater Robin Cousins, the tiny Chinese girl, Toller Cranston—these are some of the figures that I remember.

It was a whole system of dramatic juxtapositions, problem solvings, and changing configurations—those two perennial rivals (the two Brians); this skater this year, and how she was last year; the appropriateness of costumes and music, both in themselves and in relation to those of other competitors; the interractions between partners.

And nothing could ever be taken for granted, except perhaps the perfection of Torvill and Dean and the supreme athletic self-confidence of Boitano. A skater could be just a little off form that day, the tiniest of fumbles could mar a spin, a gold or silver could be lost in the last twenty seconds of a routine, a fall was never impossible. Nor could one ever be certain how the judges were going to vote, so that it was always a dramatic moment when the numbers were flashed up on the screen—9.8, 9.9, 10, 9.5, 9.6, 9.8, etc.

We agreed a lot of the time about what was in front of us; agreed that this jump wasn’t quite perfect, that that routine was perfection from start to finish. It was happy viewing.

She had done enough skating herself when young to know how difficult were the moves that the great skaters made look so easy.

II

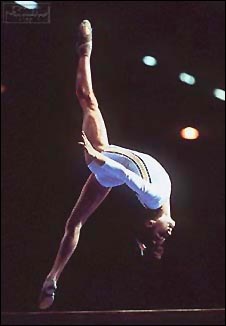

I would guess that gymnastics were for her the epitome of rigorously disciplined, high-energy, problem-solving endeavours, the athlete’s attention wholly on what was in front of her or him. It was true risk-taking, with enormous demands made upon the body at every moment as the athlete ran across the mat and hurled herself into a prescribed sequence of rolls and leaps (I’m not getting the technical terms right), or did a series of backflips on the frighteningly narrow bar, trusting to her ability to visualize the landing point that she couldn’t see, or went through the immensely taxing sequences on the high bars.

III

We watched all the snooker that came our way, and she cared about the players—puckish Dennis Taylor, with the over-large glasses, rakish Cliff Thorburn, super-cool Steve Davis, and others. Again a high-precision, high-concentration activity, in which right up to the end, as in certain kinds of drawing, the slightest slackening of attention could bring ruin. I suspect that in addition to the sheer elegance of a perfect shot, she also liked the way in which snooker players, like chess players, were thinking several moves ahead, but three-dimensionally.

She watched tennis, ski-jumping, and downhill ski racing at times, also swimming and, even more, diving. She was entirely uninterested in baseball, football, basketball, and ice-hockey. She hated boxing and despised wrestling.

IV

During Wimbledon she was in front of the box much of the time, and I would come in and join her when something particularly interesting—to me—was going on. She was usually pretty partisan; she knew who she wanted to win. I am sure that there were allegories there—the smart-ass against the sobersides, the up-and-coming youngster against the aging champion. I am sure that this year (1991), she would have rooted for Martina Navrilova, visibly tiring in her match against the physically over-endowed 15-year-old Caprioti, a sort of tennis Gletkin (an interrogator in Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon), expressionlessly returning shot after shot with indefatigable power and precision.

Next morning she would have been delighted to watch Sabatini playing confidently against what C. might have called “that big horse,” constantly varying her pace, so that power and precision were not enough, and going on to the finals against Steffi Graf. I liked the remark by one of the commentators, perhaps Billie-Jean King, that Sabatini could play any shot in the book at any time. I suspect it would have spoken to C. too.

She much preferred women’s tennis to men’s, as did I.

V

In her three favourite sports, one was especially conscious of the body in space, responding very precisely to a succession of challenges and problems. The performers had to conceptualize their performances so that they could hold an entire routine in mind, split-second by split-second; or, as in snooker, be able to think ahead for several moves and possess a wide repertoire of procedures for coping with things, adapting to constantly changing configurations

A possible allegory for her: athletes experiencing local defeats—a fall here, a failure to return an easy lob there, a run of lost games—but never giving up, throwing a tantrum, leaving the game, allowing themselves to be pushed into guilt-ridden depression.

Another allegory: the diver poised on the tip of the board contemplating space, time, gravity, water; the tennis player about to serve or receive a service and contemplating the other player’s body, the spaces of the court, the workings of the other player’s mind; the snooker player focussing intently on the whole configuration of the table before making his shot—all like artists confronting the surfaces, the fields of action, in front of them; and all absolutely alone at those moments of Zen-like focussing.

Nadia Comaneci. Photo Neil Leifer.