Network, 1981/82, oil

TV

I

TV, which we acquired late, I think in 1984, quickly become very important for her. She was lonely, she hungered for other voices, she wanted somewhere that her mind could go to when she wasn’t working. She was not reading except in bed at night before she fell asleep, often after only a page or two.

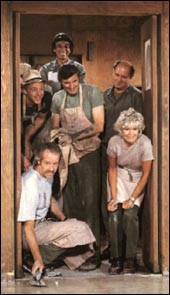

She loved several TV sitcom series—M.A.S.H, Barney Miller, All Creatures Great and Small—in which people, largely men, were practicing skills together. They had their eccentricities, quirks, small vanities at times. But they were task-oriented, and responding to the problems and the diverse individuals in front of them, and using their own best judgments. Also they were getting on well, or well enough, with each other, basically respecting each other as fellow professionals and being decent towards each other, not back-stabbing and one-upping.

Higher officialdom in these works—the Brass, the Mayor’s office, the Ministry of Agriculture—were distant and mostly problematic beings whose demands had to be coped with, but who could be ignored at times, or duped, or psyched out, and who in any event carried no moral gravitas, no obligation to be esteemed, be thought of as “superior.” Rumpole of the Bailey, Hawkeye, the squadroom characters in Barney Miller whose names I forget, were all irreverent.

She also watched each weekday in the late afternoon the to me unspeakable sitcom Three’s Company. She liked John Ritter—said he was a clever comedian and good with his body—taking falls, etc.

She watched the Muppets almost every day. Whenever I walked in upon her, she was smiling. She watched Sesame Street. She liked Jeopardy, which we often watched together.

She liked the Dave Allen Show, particularly the parts in which Irish-Jewish Dave Allen simply sat there spinning his stories, smoking, and drinking—the jokes often about Catholics (priests especially), heavy drinkers, and sex, and always, as his ingratiating bad-boy manner signalled, politically incorrect. Also The Two Ronnies, with which it was usually back-to-back.

She loved, as did I, Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister. I taped the whole series, and one of the last things we watched and laughed at in a relaxed way during her final illness was the episode—her favourite—in which the Prime Minister, in conjunction with his female Political Advisor and the quivering Bernard, his Parliamentary Private Secretary, outwits Sir Humphrey and brings him to heel by blocking his access to Number 10.

II

She followed Hill Street Blues and particularly liked the two women cops, but since I never watched it with her I can’t speak about the programme. She watched Colombo regularly. I’m sure she enjoyed seeing the fumbling-seeming professional, who doesn’t LOOK the way a detective is supposed to look, any more than she herself went around behaving like An Artist, defeating all the clever-clevers who patronise him.

She enjoyed Matlock and watched that regularly too, but a little diffidently. I was mean about it. I thought Matlock himself a bogus construct—all that quiet, warm, modest, humorous paternal strength and decency. But he was no more bogus than John D. MacDonald’s battered rangy knight-errant Travis McGee, whom I myself enjoyed, and I’m sure she would have liked to have someone like Matlock in her own adult life. I myself was a long way from being such a person, which may be why I recoiled so viscerally from him.

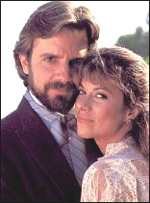

We watched Hunter together every week. I think she had a bit of a crush on Rick Hunter—tall, tough when it was called for, but compassionate and capable of a lot of tenderness in his relationship with Didi McCall. She probably envied the non-sexual intimacy between these two professionals. We watched Dempsey and Makepiece—another series about a male and female police couple. We watched Miami Vice and the British series The Sandbaggers. These were not choices that I imposed on her. She genuinely liked them.

We both especially liked the British twelve-part series The Widows, an intricate narrative about how the widows of a group of professional thieves carry out a robbery that their husbands had planned. The series was particularly rich in its presentation of the dynamics of the relationships between the very different women, and the way in which the determination of the wife of the chief robber enables them, in the face of an endless proliferation of problems, to work effectively together and survive afterwards. C. was not, as she said a lot of times, a feminist, but she admired that kind of woman.

III

All Creatures Great and Small we watched each week as a Sunday supper ritual. Siegfried Farnon was another model “strong” man—impatient, “unfair” at times, a bit peacocky, at times a bit bullying towards younger brother Tristan (who deserved it) and assistant James (who didn’t). But all that was on the surface.

An enormously decent, kind, compassionate man. Ready instantly—evening-clothed and just about to go out—to concentrate on a dog that had been hit by a car, his gaze intent, totally ignoring his clothing, saving the poor ravaged creature. Wonderful believable skills—the complete professional. Utterly unafraid to stand up to, confront, get his way with bullies or brutes or snobs or social “superiors.” But unfailingly kind to the poor and weak. Unfailingly respectful and considerate towards women like their housekeeper Mrs. Hall (“My dear Mrs. Hall!”), and immediately pleased and happy for her when hearing of her (inconvenient) intention to get married. And always watching out for the happiness of James and Helen.

James was the good soldier, treated unfairly so often by such awful Yorkshiremen—rude, abrasive, ungrateful—without losing his temper. Simply going ahead with his work, without brooding about ingratitude or feeling that he must be making serious mistakes himself in dealing with such people. His wonderful marriage with Helen—happiness of a kind that she didn’t have in her own life.

IV

But at the center, the absolute center, was S.B., Santa Barbara, during the sacred hour each day, from four to five, the programme that had to be taped if she was likely to be late getting home or would miss it altogether. For quite a while, it was a guilty, or at least clandestine pleasure, the pleasure that virtually no one else understood or approved of. She was pleased when she learned that the intellectual/soulful Russian wife of a Dalhousie Russian professor was also a devotee, though I don’t know that they ever got together to talk about it—which would have been the kind of intellectualizing, perhaps, that she disliked.

I myself felt a visceral dislike of the programme for a good while when I caught glimpses of it. But she was right, of course, about its superiority, and media people came to see that.

She was happy when it got Emmy awards—when the actors playing Eden and Cruz got awards. She was pleased by stories of how well cast members got on together. She was concerned, as who wouldn’t be, by the droppings-out, Mason’s especially, though she was glad he was (till he finally went for good) also doing stage work—Hamlet at one point, I seem to recall. She thought he’d make a fine Hamlet.

She also insisted—correctly again—that they had some intelligent writers for the show. She opined that they were probably all young, with Ph.D’s from Stanford or Berkeley. She said it must be the only soap where people quoted Wallace Stevens. She loved Mason’s problematic intensity and irony. She was delighted by Keith and Gina’s clamouring Ids. They were all very real people for her—Julia, Mrs. Capwell, and so forth—people with problems, usually family problems.

Perhaps it was the extended family that she herself never had—the family of grown-up siblings and their father. A family of competing and demanding egos, thrusting against each other, fighting against each other, being thoroughly “unfair” towards each other, and yet not being destroyed or finding that they had passed across boundaries beyond which there was no forgiveness, and from which one could not make one’s way back.

She also enjoyed the fictiveness of it all, the new subplots that the writers introduced, the characters or actors who didn’t “work.” I think she got from the series some of the pleasures that our friend Tom Roberts describes so brilliantly in An Aesthetics of Junk Fiction. There were so few genre pleasures in her own artistic work and her relationships to other artists. and the art world in general. It was very lonely work.

V

And of course there was Twin Peaks. She had liked—more than liked—all David Lynch’s movies, especially Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, and The Elephant Man, the latter on a subject that had really mattered to her ever since I introduced her to Ashley Montague’s little book on that extraordinary story. I am sure that she empathized deeply with the Elephant Man himself—brave, sensitive, and decent despite the appalling misfortune that had been inflicted on him, and his terrible mistreatment. Human despite all the marks of monstrosity and non-humanity. A paradigm of the range of the body’s possibilities. (She had also liked the movie Freaks a lot.) I’m also sure she was moved by the decency displayed towards him in the hospital, especially by Sir Frederick Treves.

I once suggested, very tentatively, that the Elephant Man might be a subject for a painting or paintings. This was before everyone took him up and he became a cult. I may have been thinking partly of Nolan’s Australian series mythologing Ned Kelly the bushranger. But the suggestion drifted to the floor and faded away. She may have thought that doing so would be exploitative and cheapening.

Twin Peaks was from the outset our kind of thing, and we watched and taped every episode. It had the same kind of combination of “normality” and strangeness that she liked so much in Buñuel, especially in The Exterminating Angel. She liked the moose’s head on the table. She liked the way in which, in this ostensibly very “normal” little town, people lived intense private lives. She liked the brief frightening explosions of violence—Bobby howling like a wolf at James in the facing jail cell. She really cared about the characters, and knew that Lynch did too—that he was never patronizing or demeaning to them.

TP became a touchstone for her with respect to the attitudes of friends and acquaintances. If one didn’t like it—and we had a couple of friends who were thoroughly snotty about it, calling it a soap opera with pretensions—it meant that they simply couldn’t see certain things, couldn’t respond to certain kinds of poetry.

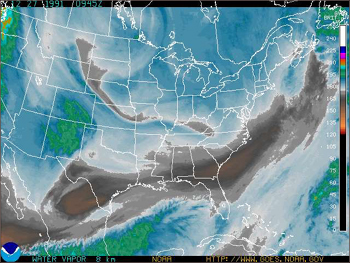

She was a keen follower of weather news.