Wallace Stevens. Photo Sylvia Salmi?

Wallace Stevens

i

By the mid-Seventies, Wallace Stevens was the poet for her, though not in the same way that Van Gogh was the artist. (I am using lower-case dividers here, to avoid confusion with the upper-case ones in Stevens’ poems).

ii

In a moving brief passage in her taped 1986 conversation with Ian Lumsden, she says that, presumptuous though it might seem for a little girl from Superior, Wisconsin, to say so, she felt that she understood Van Gogh, partly because of her background.

I think that she filled Van Gogh—that she could reach out in her mind to any aspect of his life and art, and understand and value what was there. So that even when things weren’t going well for him and his art she understood what was happening.

She understood his obsessiveness in Arles, jammed in there among his paintings, smoking poisonously strong tobacco, being slowly driven crazy, or crazier, by the toxic paints that he was using and breathing. She understood how for him there could be no such thing as sensible compromises—how he gazed and gazed, and felt the things he looked at, and had to paint them as he saw and felt them.

She understood his reachings and overreachings and at times sillinesses. She understood what it was like for him, after St. Rémy, and up in Auvers, when things weren’t going right in his paintings, the meaning-charged environment gone, the encompassing vision gone, the paintings themselves becoming coarser.

iii

On her birthday in 1958, I gave her Irving Stone’s Dear Theo; the Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh, essentially a selection from Van Gogh’s Letters. I know she read it, or read in it, though there are no pencil markings.

I’m not sure when she acquired Frank Elgar’s Van Gogh; a Study of His Life and Work (1958), which was often lying around. The pencilled price inside the cover is one pound, fifteen shillings. I suspect that she bought it on our visit to London in 1962. She told Ian in their conversation that it was then that she discovered Van Gogh’s drawings, and there are a lot of drawings in that book. There are no pencil markings, though.

She also acquired at some point the third impression (1970) of The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, edited and introduced by Mark Roskill, a 350-page paperback. There are pencillings in that, and one or two paper markers.

There are various books of reproductions, too, and the two large catalogues from the Met in the Eighties, and the discussions of Van Gogh in John Rewald’s two major books on Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

But I think that she was able to get along with relatively little reading, because she could “read” the pictures themselves and understood the configuration of Van Gogh’s mind. And I don’t think that there was anything that she could have learned about him that would have surprised, or shocked, or displeased her.

iv

I find it hard to believe that she had a strong affection for, or felt much curiosity about, Stevens the man, though no doubt she respected his ability to go on making major art up to the end, while leading an outwardly eventless life.

I don’t know that she ever read at all in the large Knopf Letters of Wallace Stevens that I bought in the Seventies. I am pretty sure that she didn’t look at the paperback selection from Stevens made by Holly Stevens with the title The Palm at the End of the Mind, which I bought, I think, in the Eighties. Nor, I think, did she read particularly in the hardcover Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens.

“Her” Stevens was essentially the Stevens of the Vintage paperback Poems by Wallace Stevens, selected and introduced by Samuel French Morse (1959), and there were probably a lot of poems in that that she didn’t read or that didn’t interest her. Apart from a handful of titles, I do not know which poems by Stevens particularly spoke to her.

I am sorry to be so vague. But Stevens was a poet who made me uncomfortable, and whose consciousness I was never able to get inside—indeed, resisted trying to get inside, though some individual poems, such as “The Man Whose Pharynx Was Bad”, spoke to me very intimately and I had various lines from “Sunday Morning” by heart.

So we didn’t talk about Stevens, and I imagine that she was glad to keep things that way. Stevens mattered too much to her for her to want me trampling across his flower-beds, as I had done with Dylan Thomas, a poet she had particularly liked.

v

Even in the Eighties I was still making derogatory remarks about the Caedmon recording of Stevens reading some of his own poems. I couldn’t follow the rhythms of his reading.

C. said that he read for the sense of the poems, and she was right. Yesterday I listened to him reading “Credences of Summer.” He reads it superbly. The poem was obviously still fully alive for him, in contrast to the way in which Eliot’s early poetry had become distanced from Eliot when Eliot read them.

At least, though, I did once or twice play Stevens’ reading of “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” for dinner guests, and may even once have read it aloud myself.

I think she must have valued, and been heartened by, the robustness, the fearlessness of Stevens’ best readings of poems on that record, and, even more perhaps, of the prose passages in which he offers declarations of faith about the nature of poetry and art.

It is a more flexible voice than those of Eliot, Frost, Pound, Williams, Winters. Though it is that of an eighty-year-old man, it is still youthful.

vi

I do not know when her strong interest in Stevens began. Probably the seeds were sown when she did “Sunday Morning” in one of Allen Tate’s classes at Minnesota. Tate apparently thought very highly of it.

(She had brought a double-text copy of Rilke’s Duino Elegies into our marriage. I found it opaque.)

vii

Which poems by Stevens did she particularly like? “Valley Candle,” obviously. It is the first text in the catalogue for her 1977 show at Dalhousie:

My candle burned alone in an immense valley.

Beams of the huge night converged upon it,

Until the wind blew.

Then beams of the huge night

Converged upon its image,

Until the wind blew.

I don’t understand it. It is followed, further down the page, by a note by her which begins with the words,

It is a strange phenomenon how one art influences another. For the past several years certain lines of poetry have been insistently nibbling away at my mind for recognition in my paintings. Because they are inexplicably present in my work I have asked that some of them be included in this catalogue.

“Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” is also included in full, along with lines from Andrew Marvell’s “The Garden” (the two stanzas beginning “What wondrous life is this I lead”) and the final section of Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” :

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! For the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain,

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

viii

Mary MacLachlan’s introduction to the catalogue opens with a quotation from Stevens’ Adagia:

The relation of art to life is of the first importance especially in a skeptical age since, in the absence of a belief in God, the mind turns to its own creations and examines them, not alone from the aesthetic point of view, but for what they reveal, for what they validate and invalidate, for the support that they give.

It closes with a quotation from his The Necessary Angel:

The paramount relation between poetry and painting today, between modern man and modern art is simply this: that in an age in which disbelief is so profoundly prevalent or, if not disbelief, indifference to questions of belief, poetry and painting, and the arts in general are, in their measure, a compensation for what has been lost.

I am morally certain that it was C. who brought these passages to Mary’s attention.

ix

With respect to other titles of poems, I shall turn to the paperback copy of Morse’s Poems of Wallace Stevens that I took this morning from the small shelf of books on the wall behind her paint table.

There is a pencilled X opposite section XI of “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery”—

The cloud rose upward like a heavy stone

That lost its heaviness through that same will,

Which changed light green to olive then to blue.

I imagine that her eye must have lighted on section XVIII on the bottom of the facing page—

Shall I grapple with my destroyers

In the muscular poses of the museums?

But my destroyers avoid the museums.

But if so, it would be characteristic of her not to mark it. I think she always shied away from self-dramatizing gestures and formulae that would, as it were, fix her in a pose. At the top of the next page there are pencilled lines opposite section XIX—

An opening of portals when night ends,

A running forward, arms stretched out as drilled.

Act I, Scene I, at a German Staats-Oper.

x

On p.73 there is a line opposite the final couplet of “The Men That Are Falling”—

The night wind blows upon the dreamer, bent

Over words that are life’s voluble utterance.

xi

The poem is followed by “The Man with the Blue Guitar.” My eye is caught by the following in section I:

They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”And they said then, “But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.”

From time to time, particularly in the Seventies, she would refer to the insatiable Nova Scotian appetite for realism, both the Peggy’s Cove seascape kind and the ostensible realism of painters like Colville and Pratt.

Nova Scotians, she remarked at one point, weren’t even interested in paintings of Provence, finding them too alien.

xii

She resisted, held at bay, shut the door on, voices insisting that they be given by the artist what they wanted. The voices might be those of Nova Scotians hungry for paintings of wharves in the rain, or art bureaucrats and Arts Canada reviewers talking about “exhibition-size paintings.”

A million people on one string?

And all their manner in the thing,And all their manner, right and wrong,

And all their manner, weak and strong?The feelings crazily, craftily call,

Like a buzzing of flies in autumn air....

xiii

But is it “them” or “us” for whom, in section V of “The Man with the Blue Guitar”,

There are no shadows in our sun,

Day is desire and night is sleep.

There are no shadows anywhere.The earth, for us, is flat and bare.

There are no shadows. PoetryExceeding music must take the place

Of empty heaven and its hymns,Ourselves in poetry must take their place,

Even in the chattering of your guitar.

xiv

There is a paper marker between pages 76 and 77 of the poem. If I had to guess what lines particularly spoke to her there, I would pick the following in section VIII.

The vivid, florid, turgid sky,

The drenching thunder rolling by,The morning deluged still by night,

The clouds tumultuously bright...I know my lazy, leaden twang

Is like the reason in a storm;And yet it brings the storm to bear....

xv

“A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” is a lovely poem about the feeling of being fully yourself, in a world that speaks to you (“In which everything is meant for you/ And nothing need be explained”), and from which dangers are temporarily absent.

xvi

There is a small triangular piece of paper, cut from a discarded watercolour, marking “The Motive for Metaphor.”

I am sure she knew the Symbolist appeal, autumnal, springtime, of states of being when

The obscure moon light[ed] an obscure world

Of things that would never be quite expressed,

Where you yourself were never quite yourself

And did not want nor have to be,Desiring the exhilaration of changes:

The motive for metaphor...,

But was it cowardly, perhaps, to be

... shrinking from

The weight of primary noon,

The ABC of being,The ruddy temper, the hammer

Of red and blue, the hard sound—

Steel against intimation—the sharp flash,

The vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X ?

She certainly didn’t care for the merely hard, the merely mechanical—the kind of thing celebrated by “masculine” art theorists and critics, like those who in the Seventies were riding roughshod over “sentimentality.” And there is a lot of metaphor-making in her work.

But she despised “soft” subjectivity herself, the kind that says, “Well, that’s the way I feel,” as if that settled it, and she valued the drive towards truth, the passion for truth and discovery.

There is something admirable about

The weight of primary noon,

The ABC of being,The ruddy temper, the hammer

Of red and blue...

And if the X is “arrogant, fatal, dominant,” it is also “vital.”

xvii

To judge from this volume, and from her occasional quotations to me from it (usually trying to see if I recognized them), the central Stevens poem for her was “Credences of Summer.”

There are a number of her pencillings here. There is a dried leaf between pages 134 and 135. (I wonder if it’s from Mexico.)

Stevens reads the poem particularly well on our record of him.

xviii

The three stanzas of section I aren’t marked, but I think she must have especially felt the lines about how, “with midsummer come and all fools slaughtered/And spring’s infuriations over,” and autumn a long way off,

... the roses are heavy with a weight

Of fragrance and the mind lays by its trouble.Now the mind lays by its trouble and considers.

The fidgets of remembrance come to this.

This is the last day of a certain year

Beyond which there is nothing left of time.

It comes to this and the imagination’s life.There is nothing more inscribed nor thought nor felt

And this must comfort the heart’s core against

Its false disasters....

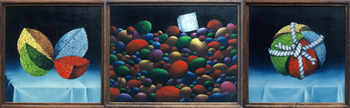

I am sure that there were times when she herself experienced, if only briefly, this kind of liberation and peace, and that she valued Stevens’ affirmation of their reality and preciousness. “False Disasters” was the title of one of her small triptychs, done around 1980.

xix

There is a line down the side of the three stanzas of section II. I will quote that section in full.

Postpone the anatomy of summer, as

The physical pine, the metaphysical pine.

Let’s see the very thing and nothing else.

Let’s see it with the hottest fire of sight.

Burn everything not part of it to ash.Trace the gold sun about the whitened sky

Without evasion by a single metaphor.

Look at it in its essential barrenness

And say, this is the centre that I seek.

Fix it in an eternal foliageAnd fill the foliage with arrested peace,

Joy of such permanence, right ignorance

Of change still possible. Exile desire

For what is not. This is the barrenness

Of the fertile thing that can attain no more.

The last line of the second stanza and the first of the third are linked by a bracket-like pencilled line. I’m pretty sure that she once or twice quoted to me the phrase “The physical pine, the metaphysical pine.”

There’s nothing ambiguous about the celebration in these stanzas of the drive towards a kind of certainty about something, a certainty that is full, not bleak, that goes on from, rather than swerves away from, the perceptions voiced in “The Snow Man” about experiencing “Nothing that is not there, and the nothing that is.”

She must have loved the opening lines of section III—”It is the natural tower of all the world, /The point of survey, green’s green apogee...”

xx

Section V opens with the lines—

One day enriches a year. One woman makes

The rest look down. One man becomes a race,

Lofty like him, like him perpetual.

Or do the other days enrich the one?

And is the queen humble as she seems to be,The charitable majesty of her whole kin?

Pencilled opposite lines four and five is the word “doubt.’”

The third and last stanza of the section ends with the words

The day

Enriches the year, not as embellishment.

Stripped of remembrance, it displays its strength—

The youth, the vital son, the heroic power.

The words “vital son” are underlined, with a question mark below them.

xxi

Section VI of “Credences of Summer” has a pencilled line down the side of its three stanzas. She quoted the opening line to me on several occasions, without explicating it, or providing its context: “The rock cannot be broken. It is the truth.” Stevens’ reading aloud of that line is especially memorable.

I think the section articulated for her especially memorably the conviction that the perceived reality of the physical world—perceived, that is, in a more than merely photographic way—is indeed there and is indeed charged with meaning and value; that one doesn’t have to go in quest of something more real behind it that implicitly devalues it.

Here are the first twelve lines:

The rock cannot be broken. It is the truth.

It rises from land and sea and covers them.

It is a mountain half way green and then,

The other immeasurable half, such rock

As placid air becomes. But it is notA hermit’s truth nor symbol in hermitage.

It is the visible rock, the audible,

The brilliant mercy of a sure repose,

On this present ground, the vividest repose,

Things certain sustaining us in certainty.It is the rock of summer, the extreme,

A mountain luminous half way in bloom...

There are rocks—granite broken off and rounded by the sea— in a number of her paintings from around 1980, when she returned to the studio after a three-year absence.

There are a number of such rocks in our garden that she brought back from the beach, sometimes carrying them a considerable distance.

xxii

In the first of my four 1990 talks at the University of Toronto about nihilism, modernism, and value, I was concerned with what seemed to me the successful struggle of various later-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century writers to get beyond the Platonism that had so poisoned the lives and minds of some of the Romantics and of figures like poor sad brave Henri-Fredéric Amiel who had to go on living after the Romantic afflatus died away.

She may have wondered why I didn’t quote Stevens, or quote him more.

I would like to think that she liked that talk, though I don’t suppose it convinced her that I had a soul.

When I was working on the talks—and I did a lot of heavy reading for them—I kept telling myself, with her theologically-minded Oak Street group in Minneapolis in mind, that I was playing for real and was all too aware myself of “the malady of the quotidian” and of how things could dwindle to flat surfaces to which no values could cling.

xxiii

In section VII there is a pencilled line running down the side of several lines, with a large question mark:

Three times the concentred self takes hold, three times

The thrice concentred self, having possessedThe object, grips it in savage scrutiny,

Once to make captive, once to subjugate

Or yield to subjugation, once to proclaim

The meaning of the capture, this hard prize,

Fully made, fully apparent, fully found.

The first “Fully” in the final line is underlined.

xxiv

Down the side of section IX she drew two lines. I am sure that those stanzas were her favourites in the poem. She quoted from them too, once or twice, waiting to see if I could identify them.

Here they are:

Fly low, cock bright, and stop on a bean pole. Let

Your brown breast redden, while you wait for warmth.

With one eye watch the willow, motionless.

The gardener’s cat is dead, the gardener gone

And last year’s garden grows salacious weeds.A complex of emotions falls apart,

In an abandoned spot. Soft, civil bird,

The decay that you regard: of the arranged

And of the spirit of the arranged, douceurs,

Tristesses, the fund of life and death, suave bushAnd polished beast, this complex falls apart.

And on your bean pole, it may be, you detect

Another complex of other emotions, not

So soft, so civil, and you make a sound,

Which is not part of the listener’s own sense.

I know she quoted to me “Fly low, cock bright,” and “The gardener’s cat is dead,” and “A complex of emotions falls apart,/ In an abandoned spot.”

I suspect that for her the lines were a broad-spectrum allegory about the losses of certain kinds of desired and familiar orderings—familial? religious? the sociable everyday?—and the possibility that even though what may seem natural and harmonious relationships can fall apart, really fall apart, they can be replaced by more important ones (“not/So soft, so civil”).

xxv

There is only one marking on “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour.” The fourth stanza reads,

Here, now, we forget each other and ourselves.

We feel the obscurity of an order, a whole,

A knowledge, that which arranged the rendezvous.

She circled “We” in the second line and put a question-mark opposite it.

xxvi

On the back cover, the poet Louise Bogan is quoted as saying,

Stevens... distills symbols, meaning, and what he calls ‘ideas of order’ from the crudity and the confusion of the actual. His ability to link the outer world or reality closely to the inner world of vision has been astonishing from the first.

That would seem to describe C.’s aim—and to my mind accomplishment—in much of her own work.

xxvii

Samuel Eliot Morse’s introduction yields a number of relevant passages. In a letter to a friend in 1953, Stevens wrote,

It is a queer thing that so few reviewers seem to realize that one writes poetry because one must. Most of them seem to think that one writes poetry in order to imitate Mallarmé, or in order to be a member of this or that school. It is quite possible to have a feeling about the world which creates a need that nothing satisfies except poetry and this has nothing to do with other poets or with anything else.

In the same letter he said:

I feel a good deal like Rilke who constantly protested that he never read reviews because he was afraid that they would disturb his unconsciousness. I think one has to read them as if they applied to someone else because there is always the danger of adapting yourself, even unconsciously, to something that has been said about you.

xxviii

I am sure she liked the fact that Stevens, according to Morse, “was much less interested in what had already been written [by him] than in those poems he hoped to write.”

xxix

I also see something answering to her own attitude in Morse’s statement that

the diffidence and skepticism with which Stevens regarded the plans for the publication of Harmonium were anything but feigned, [although] no one else knew better than he that poets were often the most ferocious of egotists,

She herself wasn’t egotistical in personal relationships and she got mad at me when I used the word “genius” once in connection with her (“Don’t say that!”).

But I am sure that part of her believed that she was doing really important and enduring work—believed it, though without putting it into words, during the times of total concentration in the studio when things were going well.

Another part of her was quiveringly sensitive and vulnerable, though.

Which is why those failed excursions to New York, Toronto, and Montreal in search of a gallery were so painful for her, and why, until the very end when she walked into the Nancy Poole Gallery in Toronto with me and Joan Martin immediately offered her a show, she simply gave up the attempt.

xxx

Morse says that

The meditative impulse was there [for Stevens] from the beginning, of course. It enriches the music of “Peter Quince at the Clavier” and gives depth to the solitary skepticism of “Sunday Morning.” So it is with certain melancholy apprehensions: the recurrent awareness of “the malady of the quotidian” and “the dreadful sundry of this world,” the search for order and “the idea of order.”

He speaks of Stevens’ reference to

“the thing that is incessantly overlooked: the artist, the presence of the determining personality.” It is this “reality” for Stevens that matters most; and it is this reality that illuminates and quickens the poetry from first to last.

He says that for Stevens,

More and more often “the eye’s plain version” of things underwent the metamorphosis of the mind; and the visible world of landscape, of “wild ducks, people, and distances,” was recomposed—sometimes transformed beyond recognition—in poems that are “of the mind in the act of finding/What will suffice,” and “secretions of insight.”

xxxi

I am getting tired. It has been a long two days on this subject. Here are some quickies by way of conclusion:

I note Morse’s reference to “a characteristic habit of making the thing observed into a thing imagined, and [a] sophisticated interest in all the devices at the poet’s command... (xvi)”

In one of his letters, Stevens says of a painter that

Here nothing is mediocre or merely correct. [He] scorns the fastidious... He is virile and he has the naturalness of a man who means to be something more than a follower.

Here is how the introduction ends:

One begins to see, finally, that almost everything Stevens wrote was grounded in his observation of the world: of the things around him, “for themselves” and in relationships to each other that revealed aspects of things—resemblances and correspondences—which a man with an eye less accurate and an imagination less acute would not have perceived. He was, to a degree that few other poets of our century have been, a discoverer.

False Disasters, Triptych, 1980, oil