Dickinson

Emily Dickinson: poems, punctuation, epilepsy

I

If I’ve given Dickinson the maximum number of poems in the Table of Contents, it’s because of the difficulty of choosing from among the 1775 poems and fragments in the 1960 Complete Poems (1789 in the 1999 one). There are more poems to dislike or be irritated by in there, depending on one’s disposition, than in any other poet of comparable distinction. There is also the pull to homogenize so as to get at the presumed essential mind there, particularly the philosophizing one, and to perceive it as being as unique in its American fashion as is, for its admirers, the poetic mind of Hopkins or, in France, that of Mallarmé.

I’ve opted for diversity, because that in itself is part of her interactions with what can loosely be called reality. There are multiple “languages” there. She isn’t always doing the same kind of thing but lapsing at times below a certain level of seriousness, or just going flat. Lightness, playfulness, linguistic inventiveness are all elements in the various ad hoc modes of being that make her heartening even when death and dying are recurring topics. Amazingly, she wasn’t, in her poetry, morbidly depressive, any more than was Hardy in his, who was also mostly at his best writing about death and the dead.

Here are a dozen more poems, not all of them fondled and smoothed (or complicated) into over-familiarity. Only the last-but-one of them made the cut into Yvor Winters’ list in the notes to Forms of Discovery of the thirty-two “irreducible minimum” of her poems that should be in any volume of selections. But they are all linguistically fresh. If one were to find one or two of them in the works of a poet like Christina Rossetti or Charlotte Mew, I think one’s antennae would start twitching. Mine would, anyway.

The sequence, as with the ten in the Table of Contents, is how they appear in Complete Poems.

II

Bring me the sunset

Bring me the sunset in a cup,

Reckon the morning’s flagons up

And say how many dew;

Tell me how far the morning leaps,

Tell me what time the weaver sleeps

Who spun the breadths of blue!

Write me how many notes there be

In the new robin’s ecstasy

Among astonished boughs;

How many trips the tortoise makes,

How many cups the bee partakes,

The debauchee of dews!

Also, who laid the rainbow’s piers,

Also, who leads the docile spheres

By withes of supple blue?

Whose fingers string the stalactite—

Who counts the wampum of the night

To see that none is due?

Who built this little Alban house

And shut the windows down so close

My spirit cannot see?

Who’ll let me out some gala day

With implements to fly away,

Passing pomposity?

She lay as if at play

She lay as if at play

Her life had leaped away,

Intending to return,

But not so soon;

Her merry arms, half dropt,

As if, for lull of sport,

An instant had forgot

The trick to start;

Her dancing eyes, ajar,

As if their owner were

Still sparkling through

For fun, at you;

Her morning at the door,

Devising, I am sure,

To force her sleep—

So light, so deep.

Answer, July

Answer, July,

Where is the bee?

Where is the blush?

Where is the hay?

Ah, said July.

Where is the seed?

Where is the bud?

Where is the May?

Answer thee me.

Nay, said the May,

Show me the snow.

Show me the bells,

Show me the jay!

Quibbled the jay,

Where be the maize?

Where be the haze?

Where be the bur?

Here, said the year.

I am ashamed

I am ashamed; I hide—

What right have I to be a bride,

So late a dowerless girl?

Nowhere to hide my dazzled face,

No one to teach me that new grace,

Nor introduce my soul.

Me to adorn how, tell—

Trinket to make me beautiful,

Fabrics of cashmere—

Never a gown of dun, more

Raiment, instead, of Pompadour

For me, my soul, to wear.

Fingers to frame my round hair

Oval—as feudal ladies wore,

Far fashions, fair;

Skill to hold my brow like an earl,

Plead like a whippoorwill,

Prove like a pearl.

Then, for character,

Fashion my spirit quaint, white,

Quick like a liquor,

Gay like light;

Bring me my best pride,

No more ashamed,

No more to hide;

Meek, let it be—

Too proud for pride,

Baptized this day,

A bride.

If you were coming

If you were coming in the fall,

I’d brush the summer by

With half a smile, and half a spurn,

As housewives do a fly.

If I could see you in a year,

I’d wind the months in balls,

And put them each in separate drawers,

For fear the numbers fuse.

If only centuries delayed,

I’d count them on my hand,

Subtracting, till my fingers dropped

Into Van Dieman’s Land.

If certain, when this life was out,

That yours and mine should be,

I’d toss it yonder, like a rind,

And take eternity.

But now, uncertain of the length

Of this, that is between,

It goads me, like the goblin bee,

That will not state its sting.

This quiet dust

This quiet dust was gentlemen and ladies

And lads and girls;

Was laughter and ability and sighing

And frocks and curls;

This passive place a summer’s nimble mansion,

Where bloom and bees

Fulfilled their oriental circuit,

Then ceased, like these.

Under the light

Under the light, yet under,

Under the grass and the dirt,

Under the beetle’s cellar,

Under the clover’s root;

Further than arm could stretch

Were it giant long,

Further than sunshine could

Were the day year long;

Over the light, yet over,

Over the arc of the bird,

Over the comet’s chimney.

Over the cubit’s head;

Further than guess can gallop,

Further than riddle ride;

Oh for a disc to the distance

Between ourselves and the dead.

Dying at my music

Dying at my music!

Bubble! bubble!

Hold me till the octave’s run!

Quick! Burst the windows!

Ritardando!

Phials left, and the sun.

I was a phoebe

I was a phoebe, nothing more,

A phoebe, nothing less;

The little note that others dropt

I fitted into place.

I dwelt too low that any seek,

Too shy, that any blame;

A phoebe makes a little print

Upon the floors of fame.

I’ve dropped my brain

I’ve dropped my brain, my soul is numb,

The veins that used to run

Stop palsied; ‘tis paralysis

Done perfecter on stone.

Vitality is carved and cool.

My nerve in marble lies,

A breathing woman, yesterday,

Endowed with Paradise.

Not dumb—I had a sort that moved,

A sense that smote and stirred,

Instincts for dance, a caper part,

An aptitude for bird.

Who wrought Carrara in me

And chiselled all my tune,

Were it a witchcraft, were it death,

I’ve still a chance to strain

To Being, somewhere, motion, breath;

Though centuries beyond,

And every limit a decade,

I’ll shiver, satisfied.

After a hundred years

After a hundred years

Nobody knows the place,—

Agony that enacted there

Motionless as peace.

Weeds triumphant ranged,

Strangers strolled and spelled

At the lone orthography

Of the elder dead.

Winds of summer fields

Recollect the way,—

Instinct picking up the key

Dropped by memory.

Summer begins to have the look

Summer begins to have the look

Peruser of enchanting book

Reluctantly but sure perceives,

A gain upon the backward leaves.

Autumn begins to be inferred

By millinery of the cloud

Or deeper color of the shawl

That wraps the everlasting hill.

The eye begins its avarice;

A meditation chastens speech;

Some dyer of a distant tree

Resumes his gaudy industry.

Conclusion is the course of all;

Almost to be perennial

And then elude stability

Recalls to immortality.

III

The morning in “She lay as in play” is evidently figuring how to awaken the sleeper. Van Dieman’s land was what became Tasmania, and, if you were a convict being shipped there from England, was as far as you could get from home.

In Webster’s New World Dictionary (4th ed., 2004), a phoebe is “any of a genus of tyrant flycatchers with a grayish or brown back.” Phoebe in Greek mythology (same source) was Artemis, “goddess of the moon; identified with the Roman Diana”; also “the moon personified”; also, “the small outermost satellite of Saturn, having an unusual retrograde orbit.” I have no idea what was in the poet’s mind at the time. I don’t know what is intended by “disc.”

“Ritardando” is defined as “Musical direction becoming gradually slower when used other than in a musical score.” The phials presumably held her medications. The poem has a discernible rhythm and isn’t just for the eye.

IV

Emily Dickinson, poète disloqué; or, Not Damned but Dashed

Yvor Winters seems to me almost spot-on in his vehement objections in Forms of Discovery (pp.264–5) to the dashes inflicted editorially by Thomas H. Johnson on a lot of the poems, like a series of hiccups. Combined with Dickinson’s over-use of capitalization, they make her more eccentric than she was, tend towards a homogenization of different styles, and interfere with her rhythms. They are a coarsening, not a refining. A poem as delicate as “Good morning, Midnight” is ruined.

At times, as in an opening line like, “Noon—is the hinge of day” she is clearly using them as if scoring for performance, slowing down a line or unit of phrasing. Most of the time, though, they are positioned where conventional punctuation marks would have been if the poems had received normal publication at the time.

Conventional punctuation marks—commas, periods, colons, semi-colons, parentheses, ellipsis marks, and, yes, dashes—are more subtle, being themselves partly, in their origins, indicators of degree of pause, but also having more complex syntactical and semantic functions. A conventional dash can be either a pointer to an appositive, like a colon—“Only one thing terrified him—hurricanes”—or, as here, be the first of a pair of parenthesis indicators, leaving the enclosed part a bit more dynamic than if one had had (“Only one thing terrified him: hurricanes”).

A fair bit of the time she seems to be getting them to do the work of commas. At others, they’re like semi-colons, holding units together without the aid of syntax. At times they’re performing like periods. At others, it can be unclear, at least on a first reading, whether a stanza has reached conclusion or we have to keep going into the next one.

Dashes are—heavy punctuation marks.

To judge from the fact that she also used dashes in letters, and, at times, together with a comma and period or two in the same poem, she simply didn’t have a sufficient mastery of punctuation to render more subtly the pausings and connectings that she was hearing.

V

Among the papers left behind by the artist Carol Hoorn Fraser are a batch of poems, or bits of poems, that she wrote as an undergraduate at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota in the late 1940s. They exist in a variety of forms—ink, pencil, typescript, print (the student ’zine)—, at times on ragged scraps of paper, at times imperfectly legible, with sometimes confusing crossings-out and substitutions, and usually undated. Transcribing them increased my respect for textual editors.

A number of them are punctuated with small dashes, little more than horizontal flicks of the pen. These were the results, obviously, of writing fast, and probably also of not being quite sure at some times of what the correct punctuation mark ought to be. The punctuation on the fair-copy typescripts and in the printed versions was normal.

I would imagine that she was by no means unique among girls of her generation in punctuating like that.

VI

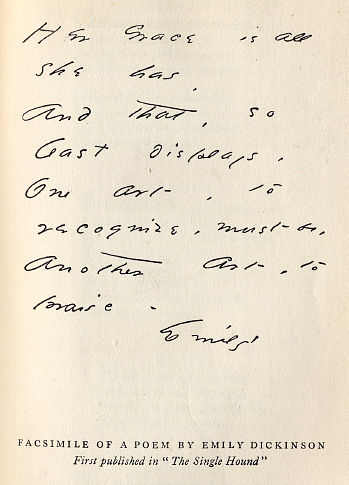

The following facsimile, facing page 266 of The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Alfred Leete Hampson, shows how much lighter and more wavering Dickinson’s own markings could be. The one-stanza poem or jotting for a poem goes:

Where the evidence of the eyes is concerned, Johnson’s decisions as to which of those particular specks is what seem wholly subjective.

VII

Dickinson’s over-capitalization is also a coarsening.

Partly it is simply the automatic capitalizing of nouns, as is still done in German, and which continued in British poetry until at least the middle of the eighteenth century, as in, “The needy Traveller, serene and gay/ Walks the wild Heath, and sings his Toil away” in Johnson’s The Vanity of Human Wishes.

But at times, a number of times, it’s evidently intended to give a special weight to a word functioning as a proper name (“Good morning, Midnight”), or charged with ad hoc significance (“I’ve stopped being Theirs”), or, as in “Is Bliss then, such Abyss,” making an abstraction more concrete or a concretion more abstract, rather as happens in French with the omnipresent particles—la verité, the truth, instead of just “truth.”

The trouble is, one doesn’t always know when she’s doing what.

VIII

I said above that Winters’ critique of Johnson’s texts was almost spot-on. I’d failed to read, or at least to notice, the following by Johnson himself in the variant-readings Harvard Poems of Emily Dickinson (1979).

Her use of the dash is especially capricious. Often it substitutes for a period and may in fact have been a hasty, lengthened dot intended for one. On occasion her dashes and commas are indistinguishable. Within lines she uses dashes with no grammatical function whatsoever. They frequently become visual representations of a musical beat. Quite properly such ”punctuation” can be omitted in later editions, and the spelling and capitalization regularized, as surely she would have expected had per poems been published in her lifetime. Here however [ in the Harvard edition] the literal rendering is demanded.

(lxiii, italics mine)

If so—I mean, if the oddities and anomalies of the Johnson texts are simply there , for him as for us, for the limited purposes of what is thought to be an accurate conflation of the various sources—then the whole game opens up, since there is no obligation for compilers of selections to wait for a definitive normalized text of the whole oeuvre. There never can be such an edition.

That was over half-a-century ago. But the dashes have clung in there with bedbug tenacity.

IX

Obviously there are problems with becoming to some extent a textual editor oneself. But it seems an abnegation of responsibility to say to the general reader, in effect, “Make up your own mind.” Of course editorial errors, or what are claimed to be errors, occur. But a text doesn’t crumble into vacuity because of a misreading or two, and the gains in readability with normalization, as discernible in several selections from her work, far outweigh possible drawbacks.

What’s that? “Readability”? Don’t we know that, like Mallarmé, an experimental poet like Dickinson is meant to be difficult?

Well, as a matter of fact, yes, she is indeed Mallarméan (or he Dickinsonian) in her transpositions of psychological abstractions into concretions, and her syntactical daring. But if, as one reads along, one has to keep dealing with avoidable syntactical difficulties and unintended ambiguities in the interests of maintaining her status as a proto-modernist, one will be less able to appreciate her expressive originality, including her reworkings of “popular” elements that relate her to Hardy.

X

Given the penumbra of uncertainty around a lot of her poems—uncertainty as to whether a transcribed poem is hers at every point; uncertainty as to whether something is wholly finished up; uncertainty as to which of two variants she would finally have settled on; uncertainty as to what would have happened, and with what degree of approbation on her part, had the punctuation been normalized for publication during her lifetime—textual decisions will unavoidably at times, as that ferocious textual editor A.E. Housman knew, be partly critical ones.

Does something feel right, bearing in mind the whole progression of a poem, and what goes on in other poems by the author which in some ways it resembles? Does a particular difficulty feel like one that inheres naturally in one or more of the author’s modes—or not?

And often, at least until we get into the later and at times obviously hurried jottings, it seems to be mostly a matter of an occasional crux, some problematical local piece of diction, syntax, or punctuation. If, with Johnson, you’re happier with the penultimate line of “This quiet dust was gentlemen and ladies” as “Exist an Oriental Circuit,” rather than “Fulfilled an oriental circuit,” well, both versions (see Johnson) are in the sources.

Ditto with “No one” as opposed to “No man” in the final stanza of “I started early.” Personally I found the former puzzling before I knew that there was another option. He’s a stranger there? He enters the town? What? Whereas “No man he seemed to know” suggests a gentleman so intently focused on the lady he’s dogging along the road to town that he has no interest in any men coming the other way and ignores the normal hat-raising courtesies.

(Johnson’s mystifying choice of “at most” over “almost” in “Summer begins to have the look” is a non-starter.)

It also, so far as I can see, doesn’t in fact matter greatly, most of the time, so long as the syntax is reasonably clear, whether at some particular point there’s a semi-colon or a period, a colon or a dash. Her use of those pen-flicks testified to a desire to keep things flowing, rather than crispening them up, including flows at times from one quatrain to the next. A quatrain poet like A.E. Housman she isn’t. Rhymes are not emphatic boundary-markers. They can miss precision, at times even vanish.. And the poem isn’t necessarily wrecked.

XI

In any event, one needs to resist the temptation to believe, especially where Dickinson is concerned, that the more difficult is always to be preferred to the less, and that the more gnomic something is, the better.

That belief has its pedagogical advantages, of course. The deeper the difficulties, the more the teacher is needed, the more the students can indulge in interpretive ingenuity, and the more reassuringly distant the poet becomes from the seeming simplesse and preachiness of a lot of the poems. Also, one is emphatically not being guilty of the kinds of smoothings and simplifyings of lines by poets like Shakespeare, or Hopkins, or, as done by her early advisor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Dickinson herself, that have become Awful Warnings.

And once a text is solidly there in print, it willy-nilly looks authoritative, as if the author Has Spoken. Logically it needn’t. But it does. And Johnson’s is a Harvard publication, I mean HARVARD.

But the belief that Harvard is some kind of critical Mount Olympus seems to me one of the embedded academic myths, and I find reassuring the statement by Stanford’s Winters that: “there is no question about one thing: the early versions, especially those of Mrs. Todd, are the best poems, and by a wide margin” (Forms, 264).

Winters was a greater critic than anyone who ever operated out of Harvard.

XII

The disposition to see profundity as inhering in individual words and phrases from which it can be extruded under the right pressure—a disposition going back to the Romantic belief in the synthesizing power of the Imagination, and adrenalin-boosted by William Empson’s Fifty-Seven Types of Ambiguity—in fact hinders an empathetic participation in the start-to-finish heard progression of a good or great poem.

And with a poet like Dickinson—whose best poems, as Winters points out, are often not instantly different from her preponderant worst—to extrapolate from the best ones and make the others all part of the postulated Mind of the poet can in fact, like a photographer’s preponderant weaker photographs, cast doubt backwards upon the distinction of the best ones.

As happens for me, I must confess, when I run my eye over the forty-one poems in the 2006 Oxford Book of American Verse, with the drum-taps of those dashes signaling, as for a contingent at a summer-camp jamboree, WE ARE EMILY DICKINSON POEMS.

The even more generous selections in one or two other anthologies, particularly when specifically Christian items are excluded, make me wonder whether she hasn’t become, for some readers, a sort of higher-level replacement for the spirituality of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet.

XIII

Was Winters’ right in his trail-blazing claim in Maule’s Curse (1938) that “except for Melville, she is surpassed by no writer that this country has produced; she is one of the greatest lyric poets of all time.”? (In Defense of Reason, 299)

I don’t know. By my count, there wouldn’t be more than seventy of her seventeen-hundred-and-seventy-five poems in a volume of her poems picked strictly for their poetic merit, rather than as components of the Emily Dickinson Story. That’s not a bad score, and anyway, greatness, as Winters rightly insisted, is not a matter of bulk. But there are numerous poems in A New Book that speak to me more than do hers.

In any event, exploring her in Johnson’s edition is a lot more interesting than doing so in the 1933 Bianchi-Hampson Definitive Complete Edition, a thousand poems shorter.

I’ve tried to pick poems that can stand on their own, that have varying degrees of seriousness without, at the lighter end of the spectrum, being merely cute, and that display, for the most part, her remarkable stylistic inventiveness. In other words, I’ve tried to approach her as a normal maker and shaper of poems, rather than as a cult—a maker and shaper who can obviously enjoy the element of formal play.

XIV

I have now read R.W. Franklin’s introduction to his reading edition of Dickinson, and his bibliographically formidable The Editing of Emily Dickinson; a Reconsideration (1967).

It’s curious.

His evidence and arguments almost all serve to support and develop that crucial paragraph of Johnson’s. An examination of her manuscripts, he reports in Editing, shows that they “were merely a habit of handwriting and that Emily Dickinson used them inconsistently, without system.” The capitals were “used on nouns, but not every noun, at times on every other part of speech, and on important and unimportant words alike.… Frequently several autograph copies of the same poem exist, each with variant punctuation and capitalization.”

Moreover, “That the capitals and dashes were merely habits of handwriting without special significance is also shown by the poet’s using them not only for poems but for letters too,” and by how, when she copied out passages from other writers “she translated type into her own peculiar writing, complete with capitals and dashes where they had not been.” (120-121)

Furthermore, a box containing “some of the correspondence associated with the nineteenth-century editing of the Dickinson poems” includes “at last thirty letters by twenty-four different writers in which the dash was used in place of conventional punctuation.” (124)

But when Franklin quotes her verse, the dashes and capitals are still there. And they are there twenty-three years later in the Reading Edition accompanying his own variorum edition.

XV

Presumably Harvard wouldn’t spring for a modernized reading edition to accompany Franklin’s two-volume variorum, though it would be nice to think that he had tried to persuade them. After all, he himself had said in Editing that

an editor is needed to produce, not as a substitute for the variorum but as an addition to it, a readers’ text whose capitalization and punctuation conform to modern usage. The task yet remains to be done. (128)

But the extra work would probably have been daunting, and no doubt market research had indicated that a lot of readers at various levels of sophistication genuinely liked, or weren’t bothered by, the typographical idiosyncracies.

However, his apologetics on behalf of the status quo in his reading edition are so perfunctory that it’s hard to believe that he was really trying.

When he says straightfacedly, “The basic choice has been either to follow her private intentions and characteristics … or to lay onto the poems social conventions and judgments that were not hers” (11) such a dichotomy and its subtext would de-legitimize legions of edited texts by earlier authors. After all, lots of those poets too must have wanted their poems to appear the way they did, and have felt them in that way, subtly, while writing them.

And Franklin himself had said in Editing that “We lack … authorial final intention throughout the poems of Emily Dickinson.” (133), and that

Multiplicity … did not bother this poet, and she would without qualms change a reading in order to make it appropriate for different people and different occasions. Each of these fair copies is “final” for its person or occasion, but that cannot be equated with final intention for publication. (132)

XVI

Crucially, too, when several of her poems were published in the normal way behind her back,

She is known to have complained only once—about a question mark in “A narrow fellow in the grass” that stopped a line whose thought should have continued into the next. She said nothing adverse about typography or its effects on her poems. A good citizen of the age of print, she was a committed reader of newspapers, magazines, and books but could not undertake the commercial, impersonal, and fundamentally exposing act of publishing her work. (Reading Edition, 5)

She obviously had her heroic pride, but she wasn’t a megalomaniac like Gertrude Stein or Laura Riding.

Are we seriously to believe that this exquisitely sensitive and by no means unself-critical poet, with a piquant sense of humour, who read with appreciation and empathy the work of others, such as the Brontes, and didn’t need conventional publication (as distinct from circulating MSS among friends and relatives in an almost Renaissance fashion), would, if given the option, have insisted that her poems alone, out of all the infinitude since the dawn of publishing, be singled out typographically in the Johnson-Franklin fashion?

That kind of vanity is not the path of the kind of genius that she is thought to be.

XVII

Obviously there’s a sizeable element of de gustibus here, given that there are intelligent readers who like the features I am referring to.

Presumably the dashes and capitals slow down for them the movement of what might otherwise be too-tripping lines (her favourite 6-6-8-6 stanza form being Hallmark-easy to write) and provide more of a sense of presence, as if the poet herself were reading out the poems with appropriate emphases.

But conventional punctuation does the job better, being more semantically precise and allowing one more freedom to hear the movements of the lines in one’s own fashion.

And the feeling, analogous to looking at a painter’s free-hand drawings, that one is really getting close to her now is delusory. Those stiff, straight, uniform horizontal lines breaking up the flow weren’t those of her hand in motion. If the latter is what one wants, and with it a feeling of her making those marks as she writes, rather than mechanically inserting them later, one had better go to facsimile copies of manuscripts, with their much greater variety and subtlety.

Such as, I see on Abebooks, Franklin himself provided in what sounds like a mouth-watering, and very expensive, manuscript edition of her poems and hand-made little books.

That was a quarter of a century ago. Surely hoi polloi deserve a cheaper edition now, or at least a volume of selections.

But no gain without pain. The difficult handwriting at times, and the erratic lineation, particularly in the letter-poems or poem-letters, can fatally disrupt the poems as rhythmic progressions in time and diminish them to forms in space. And since handwriting itself, as an alternate symbolic system, can be much more expressive than mere punctuation marks, presumably to get as close as possible to her spirit as she composed, without recourse to a spiritualist medium, each text would have to be accompanied by an analysis by a competent graphologist.

But which graphologist …?

Will the regress never end?

XVIII

As usual, Winters speaks with admirable clarity.

Edith Perry Stam has published an article which purports to explain the origins of the dashes. According to Professor Stamm the dashes are not dashes in the manuscript but are marks of various kinds intended to indicate the proper intonation for reading aloud; the marks were derived from a few books of elocution in common use at the time and in use in the Amherst Academy while Miss Dickinson was a student there. The marks as they are described in these texts, are all easily translatable into punctuation marks, and Mrs. Todd would appear to have so translated them without comment. If Professor Stamm is correct, Mr. Johnson translated them all into dashes. Professor Stamm in turn has been criticized; but it would seem that Miss Dickinson was not whole-heartedly devoted to dashes, and it is certain that the dashes ruin her poems. (Forms 264)

Whether or not it is as exact as that, she was obviously hearing as she composed, and signaling to herself, her words having the private aura that words always have when a strong self is holding pen or pencil.

In Johnson’s transcription of the facsimile passage reproduced earlier in this note, dots become dashes. Dots, as witness the Morse Code, are not dashes. And dashes like Johnson’s and those of too many others occupy a curious intermediate position between conventional punctuation and voiced directives like those in Japanese cars—a kind of unvoiced sound, as it were.

Franklin’s dashes are less brutal, but reminding oneself what their tripartite options signify is still distracting, and other presenters and their publishers aren’t using them.

XIX

Playing textual editor myself in these pages, I’ve found myself preferring the “period” texts of a number of older British poems that I’ve transcribed, with the capitalization of nouns, the italics for proper names, the older spellings, and so on, all serving to slow the reading down and counteract the tendency to flesh things out in present-day terms with one’s mind’s eye.

But at least there are consistent principles at work there. And with some texts, particularly Scottish ones, when you’re hearing them in your mind’s ear with something resembling a correct pronunciation, words that are difficult to the eye can become recognizable to the ear, and, yes, the whole acquire more of the texture of living speech.

XX

Evidently, too, with Dickinson’s image, as with Whitman’s, we are into narratives of American exceptionalism in which the two of them have come to be perceived as the great American poetic prophets, in the biblical sense, with every utterance by them of consequence—Whitman engaged in a “masculine” reaching ever further and more comprehensively out into the “real” social world, Dickinson going deep deep deep into the “feminine” soul.

And in this perspective the eccentricities, while weakening the best poems, serve to bring the others up by implicitly emphasizing that they’re all from the same dash-flicking and capitalizing mind.

XXI

However, true though de gustibus may be of oysters, and Retsina, and brains (the edible kind), and though one may grant the factuality of objections to a movie and still enjoy it, de gustibus can be a cop-out.

As with anonymous texts like ballads, editorial decisions about Dickinson, including those of anthologists, are inescapable. One is thrown back on what feels right, given the internal progression in a poem, and what goes on in other poems by her—or by her with changes made or suggested by others.

As Franklin points out, it can be comforting to believe that in a Platonic world there exist the final-final ultimate perfect versions of poems, going beyond even the nominally final texts published with their authors’ approval. Yeats, after all, was revising up till the end, and who is to say what changes Keats might have made to the rewritten Hyperion had he lived longer?

But are revisions necessarily always improvements?—I mean, if one doesn’t subscribe to the Romantic idea of poet-as-inspired-visionary? And can every poem that’s embarked on be brought to a satisfactory conclusion?

Franklin himself turns weirdly Platonist—or German-Romantic—with his suggestion that “Poems are neither self-generating nor self-maturing, and those which lack completion by Emily Dickinson will have to be finished by an editor.” (Editing, 145, italics mine)

Upon what compulsion—I mean, apart from the hypothesis that once a writer has been determined to be a “genius,” each work that she or he embarks on contains in it the seed of an organic perfection? And how do we know when a writer is a genius, or even just a Real Poet rather than a Mere Versifier? Why, because (presumedly) each work that he or she embarks on contains the seed of an organic poem …

There used occasionally to be a requirement that taking a degree in art history required a class of old-fashioned art craft—drawing, painting, sculpting, not in order to generate creativity but to instill some idea of the kinds of things that can go on during the act of creation.

Did Franklin, I wonder, write poems seriously himself when young?

XXII

And while, in the sublunary world, one may choose to talk about “authors” as if they, like their poems, possessed a transcendental organic unity, a self like an underground lake into which buckets could be lowered and works drawn up, or in which they simply bubbled up to the surface, what in fact we have are texts requiring to be read by critics in an Aristotelian fashion (Franklin’s term).

Which is to say (my gloss), focusing on the dynamics of the speech-acts, going on discernibly in this or that cluster of words on the page for what they are in themselves, and in relation to other works, rather than as indices to the “minds” behind them.

The objection to weaker and inconsistent-feeling stanzas in a work, such as a traditional ballad, is not that they may signal inauthenticity, but that they are weaker and inconsistent-feeling.

In whose eyes? Well, as Ollie says to Stan on one memorable occasion, let’s not get into that.

XXIII

There is no ultimate finality here. But value-constructions aren’t simply arbitrary and subjective. And we have no trouble existing with twenty or thirty different renderings of a jazz classic without agonizing over which is the “true” one.

The effective controls or pointers are those of metre, syntax, diction, rhyme, and the operative conventions set up, or seeming to be set up, at the outset of a poem. When a syllable is missing in otherwise normal metres, or a rhyme is askew in otherwise consistent rhyming, or something seemingly inconsistent happens in the syntax, then, when “period” practices don’t seem sufficient explanations., it can be time to start speculating about a damaged text, and feeling around for what, in terms of the progression thitherto, feels right.

If someone reported having heard an epigram that went, in his jotted-down version,

Here lies Sir Tact, a dipsomatic fellow,

Whose silence was not golden but just yellow,

and if a glance at a few other poems by the author disclosed no eccentricities of diction, and a disposition towards maximum concentration, it wouldn’t be beyond the powers of the Aristotelian intelligence, with its concern with how things work, to figure out that “diplomatic” might be better here than “dipsomatic”—and that that was what the author (Tim Steele) had most likely said.

And if someone were puzzled by a poem like

Hands, do what you’re bid:

Drag the balloon of the mind

That bellies and sags in the wind,

Into its narrow shed,

and went to other poems in The Wild Swans at Coole, such as “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory,” he or she would soon realize, that, no, the near rhymes here and elsewhere in that volume are not the result of authorial incompetence, or too much Irish in his poetic bloodstream, but are important elements in Yeats’ stylistic tool-kit.

But no doubt if, because of a typo, an edition of Macbeth had gone out into the world in which Macbeth’s great soliloquy upon being told of the death of his queen had begun, “Out, out, brief cuddle,” there would have been teachers eagerly instructing their young charges in the brilliance with which all the passions of the flesh were summed up and dismissed in a single colloquial word.

XXIV

By all accounts, Yvor Winters, in his small-group poetry-writing seminars, was exceptionally good at discerning the direction in which a poem was trying to go. As was apparently, in his editing of Latin texts, A.E. Housman in his capacity of Professor of Classics.

In the section on Dickinson in Forms of Discovery from which I have already quoted, Winters says flatly, and fascinatingly,

I have not seen the manuscripts and cannot judge, but there is no question about one thing: the early versions, especially those of Mrs. Todd, are the best poems, and by a wide margin; furthermore they were a part of our literature for a good many years, and are bound to remain a part, no matter whether they are ultimately described as the works of Miss Dickinson or as works of collaboration. They should be kept in print. (264)

Some criticism gets superceded, such as Samuel Johnson’s vastly overpraised remarks about Shakespeare, where he is good by virtue of not being as bad as he could have been. But the perceptions of a great critic, as Winters was, may be so significantly on target that subsequent work by others, whatever its sophistication, doesn’t supersede it.

XXV

Franklin seems to me right on target, though (and Wintersian) when he says, in Editing, that logically what we should all be talking about is poems, but that we (well, not all of us) have opted for poets.

Which is to say, if I may extrapolate, opting for “minds” embodying their insights in verse, particularly the insights of “real” poets, in contrast to texts as speech-acts incarnating possibilities of a variety of kinds, to be approached without preconceptions as to their intrinsic worth and interconnectedness.

From which, as they accumulate, an in fact more accurate sense of a self, or aspects of a self, may emerge.

And this in fact facilitates the engagement of “ordinary” readers with poems, including ones where there isn’t a “personal” speaker to identify with.. One becomes such a reader, or browser in anthologies, by, well reading, without the equivalent of a tour guide’s shepherding through an art museum. One internalizes poems, beginning with the rhymes of childhood, where one enjoys the strong beat and elliptical language of nursery rhymes.

Vastly popular anthologies like Palgrave’s Golden Treasury and Quiller-Couch’s Oxford Book of English Verse came to their readers and delighted them without any editorial apparatus at all apart from, in “Q’s” book at least, the dates of the poets. “Reading” the poems was not made difficult because of that, let alone, to use one of the theory-cliché terms, “impossible.”

XXVI

As Jacques Barzun pointed out years ago in Teacher in America, students should be reading extensively and picking up patterns and procedures, and not merely intensively, with each work becoming sui generis and inviting the scrutiny of the watchmaker’s loupe, appropriate though that may be at times.

Which is why the critical faculties are liable to deteriorate if one specializes too long or too narrowly in a particular author, given the impulsion to find merit everywhere in his or her oeuvre, and to exclude larger questions of critical theory and literary principles as not being applicable in this particular field. I was once told in all seriousness by someone with a heavy investment in Yeats that he could see no difference in quality between “The Tower” and “Meditations in Time of Civil War.”

XXVII

In speaking up, as I have, on behalf of reading poems for themselves and not for the light that they are believed to throw on what are presumed to be the inner realities of their authors, I have not been dissing as such the holistic approach in which one indeed talks about “poets” and not just about poems.

Poets are just as much subjects for biographical explorations as admirals, or brain-surgeons, or queens (of both varieties), or stunt-men, or serial killers, or presidents, or championship golfers, or atrophysicists, or robber barons. With all of them one is looking at texts of one kind or another, and trying with their aid to construct accurate accounts of what was actually done and said in the physical world of consequences—looking at letters, journals, reminiscences, photos, interviews, books, media reports, etc.

And poems too are texts, but without any special truth-bearing status that makes them intrinsically more reliable than the other minds.

The important thing is not to muddle up the two approaches, which often entails extracting from weaker poems, especially when they appear to be autobiographical, a self that is then read back into the stronger ones.

The moment someone presumes to tell us with an air of certitude what X or Y was “thinking,” or “feeling” at such or such a time, as distinct from what they wrote in a letter, or a poem, or are recalled by someone to have said, there are problems,. When we’re told that, “Shaken, unprepared. Emily remembered that the day before her father left for home she had wanted to spend time with him, and as the afternoon stretched out he had said, “I would like it to not end.” (Gordon 157), how on earth can the biographer or we know that? That’s fiction-making, fiction being a genre in which we can indeed accept as true the statements about what’s going on in the heads of characters.

Part of the greatness of Boswell’s life of Johnson, or Hester Thrale’s invaluable supplement to it, is that they are always about what Johnson said and did and wrote, not about the uninspectable workings of his mind. What doesn’t, of course, preclude our making inferences about the painfulness of that heroic life marked by so many early failures.

XXVIII

I have now, by way of a bit of self-education, read Lyndall Gordon’s Lives Like a Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds (2010), Alfred Habegger’s My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: the Life of Emily Dickinson (2001) and Johnson’s three-volume edition of Dickinson’s letters.

She was and is a difficult subject biographically.

The letters are something of a devastated war zone, with so many letters not having survived (the gaps especially gaping for 1863–64), and too many others reproduced here from 19th-century editions, accompanied here by the ominous editorial words, “Manuscript destroyed,” and the letters from others to her having been destroyed at her request by Susan, her sister-in-law, upon her death.

One can see, too, why Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an intelligent and sensitive man, and a fine soldier in the War, where he commanded the first all-Black regiment of ex-slaves, should have said in 1870 that “I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her. She often thought me tired & seemed very thoughtful of others.” (Letters, II, 476.)

Admittedly he was reporting on a recent couple of conversations to his wife, who may not have been eager to hear about meetings of minds from which she herself would have been excluded. But during Dickinson’s brief years of greatest poetic activity in the early 1860s, the leaps, compressions, and at times private or semi-private associations and allusions in her letters are a very heavy trip.

And the dashes, while at times functioning a bit like those conversational ones in Sterne and Dickens, at others give the impression that she was going off her rocker.

Please do not take our spring—away—since you blot Summer—out! We cannot count—our tears—for this—because they drop so fast—and the Black eye—and the Blue eye—and a Brown—I know—hold their lashes full—Part—will go to see you—I cannot tell how many—now—It’s too hard—to plan—yet—and Susan’s little “Flask”—poor Susan—who doted so on putting it in your own hand.

II402

To judge from how relatively seldom she is engaged in ongoing dialogues in those years, taking up points or facts provided by correspondents, her outpourings can seem at times those of an isolated egoist (however idealistic) who is speaking more to a private construction in her head than to this or that actual flesh-and blood recipient. No wonder letters went unanswered at times.

The three drafts of letters (unsent?) to her so-called Master (i.e. teacher) seem what hearty wholesome philistine Brits would call barking mad, unless one postulates a recipient of much more than ordinary sensitivity and understanding.

Did such a one actually exist? Or was she projecting qualities onto, probably, Charles Wadsworth, that he didn’t possess, a not uncommon phenomenon during attacks of love as a coup de foudre, here a more concentrated version of the hunger to be together and communicating perfectly displayed in her earlier letters to Susan.

She herself spoke in 1869 of how

A Letter always feels to me like immortality because it is the mind alone without corporeal friend. Indebted in our talk to attitude and accent, there seems a spectral power in thought that walks alone.

(Selected Letters, 196)

Literary theorists who slap the label “Augustan” onto Yvor Winters might ponder the paradox of his unabated admiration for a writer so little a rationalist in the conventional sense of the term, and living so near the perilous edge. Higginson later called her “half-cracked.” No wonder she felt a kinship with Emily Bronte.

XXIX

The storms in and around that family compound in Amherst may have been interior, but the emotional turbulences, what with religious revivalism, risky financial ventures, muted eroticism, and the omnipresent New England death rates (sixty-two deaths in Amherst in 1865 alone, a number of them from the always lurking “consumption” that could make an ordinary cough ominous) were obviously intense, even with stiff-lipped paternal silences. At one point one finds one of the three siblings—Austin, Emily, Lavinia—wondering, as must have done the Bronte ones, why they had to be “different.”

And when, near the end of Emily’s life, pretty, bright, ambitious, young Mabel Loomis Todd enters Gordon’s narrative, and the affair with Austin begins, and the family angers that continued into the twentieth century with such consequences for the Dickinson texts, it becomes virtually a novel, one curiously without, so far as one can see, New England sexual guilt of the Scarlet Letter variety.

Brother Austin, around the time of his marriage to the handsome and intelligent Sue, had even looked like Heathcliff.

XXX

But “difficult” though she was as a subject for enquiry (both Harbegger and Gordon speak of her role-playing, her at times almost pathological secretiveness, her gnomic utterances), it’s still not hard to see that Harbegger’s approach to her is a right one, and that Gordon’s is not.

XXXI

Gordon’s theory that Emily was epileptic and became reclusive because, presumably, not wanting to go into a fit while out buying three yards of dimity or taking tea with the neighbours is irrelevant to the great poems, which Gordon rarely alludes to, and is an impertinence if one thinks in terms of a degrading loss of control—of prim Miss Emily writhing and bucking on the floor in a grand mal seizure.

That by itself wouldn’t rule it out. But it is an implausible solution to a misconceived problem, namely why a supposedly normal sprightly girl should have become an increasingly reclusive woman.

It’s conspiracy theory, and like numerous conspiracy theories, relies heavily on a microscopic scrutiny of small bits of text, without a sense of holistic probabilities. The problem with any conspiracy involving more than three—well, five— persons is keeping it secret. Words travel.

Grand mal seizures can be horrible to witness. During morning assembly at my secondary school, a boy who subsequently laid his neck across a railway line one night had one. It wasn’t something that you forgot. New Englanders may have been notoriously reticent about themselves individually, but gossip about others was social entertainment, and all you needed was one, well, one or two, grand mal seizures by Emily, member of an important family, at college or in other public milieus for the word to be out.

Petit mal seizures, to judge from a bit of googling, while at times or often undiscernible to the eye, other than as moments of absent mindedness, don’t persist significantly beyond adolescence.

Moreover, if it was grand mal that was in question, when Dickinson herself said in 1884 that recently “I had fainted and lain unconscious for the first time in my life,” (307), one presumably would have to invoke those all-purpose hypotheses that she was lying (“role-playing”) or forgetting, arguments that can’t be refuted except in terms of probability, since in the absence of further documentation they can’t be proven.

And when, “decades later, old and bitter,” Otis Lord’s niece “reportedly said of Dickinson: ‘Little hussy—didn’t I know her? I should say I did. Loose morals. She was crazy about men. Even tried to get Judge Lord. Insane, too,” she didn’t add, “Had fits.” (Habegger 591).

One also has to do some serious contorting in order to convert the earlier references to Emily’s problems with her eyes, and her visits to, and periods in the hands of, a well-known opthalmologist, into coded references to—ta-dah!—epilepsy and its treatment. And to judge from a communication on the Web, Gordon is mistaken about the nature and medical function of glycerin.

XXXII

As I said, Gordon supplies an unconvincing solution to a misconceived problem. She writes as though Emily started out as a normal, lively, sociable girl, with a gift for verse-writing, who progressively withdrew from normal social relationships, until she would literally remain hidden when visitors whom she cared about came to call, and who didn’t do what normal young women did and want to get married.

But withdrawals can occur intelligibly, and not just pathologically.

Contacts with people who thought they knew the place of everything in the world and could tell when someone was aspiring too high or sinking too low in relation to a norm would have been an intolerable and invasive strain for her. She was obviously conscious of a lack of face-to-face social skills, and of the possibility of saying something inappropriate and making a fool of herself or giving offence.

Far better to stay apart and communicate by letters including sending out poems in MSS to what she believed to be sympathetic readers (179 in 1863 alone, according to Gordon). Had there been computers back then, she would have bonded with hers.

Pretty obviously, too, while she yearned at times, as at the outset of her friendship with Higginson, or later, with Judge Lord, for the overarching security provided by an approving and comprehending male, the closeness of equals—of, in effect, twins—that she felt in her relationship with Susan before the latter’s marriage, who comes across as sensitive and intelligent in one of her letters, would only have been possible with a woman. Which, no, does not make her lesbian.

There’s only a mystery to be solved as to why she didn’t marry if one assumes that marriage would have been the normal thing for her, and a source of pleasure.

But she was not normal, which is not the same thing as saying that she was abnormal sexually. She was ontologically fragile. Can anyone seriously imagine her in the bedroom with a husband on her wedding night? Or pregnant? Or raising a child, or children? Could she have imagined that herself, I mean as something pleasurable to look forward to? Could she have managed a single day and night of the total loss of privacy that marriage even with an ideally sensitive male would have entailed?

Tiny Charlotte Bronte, marrying late, had died in childbirth in 1855. Dickinson would presumably have known about that.

XXXIII

Gordon reports that in 1924, Mabel Todd told her daughter Millicent that

there were actually two men in Emily Dickinson’s life, and no distinct tragedy, “and it scarcely influenced her life in any detail.”

“She enjoyed writing her love poems more than she enjoyed the man, I sh[oul]d be willing to say.”

It indeed makes some difference at times whether a poem is addressed to a man, a woman, or what passed with Emily for a deity, or an ideal guardian and teacher (the “Master”).

But yearning is still, poignantly, yearning, whether voiced in her letters to an absent Susan or in a poem like “If you were coming in the fall.”

XXXIV

Gordon’s introduction of epilepsy as the Hercule Poirot solution to a presumed problem is dumb-bright (cf. jolie-laide) and, so far as the common image of Emily is concerned, demeaning, because reducing her to victimhood, automatism, and ongoing dread of public opinion. It also, of course, makes her more manageable to the kinds of readers who take the New York Times Book Review seriously, and for whom poetry is essentially an affair of interesting personalities talking interestingly about their interesting lives and sharing interesting and sometimes profound opinions and insights with us.

Rather than being interesting speech-acts—cajoling, pleading, demanding, celebrating, pondering, entertaining, flattering, deriding, confessing, recalling, mourning, judging, yearning, regretting, memorializing, consoling, etcetera.

And the enlightened are empowered, vis-à-vis the poet, by their enlightened knowledge: “You poor dear thing, you shouldn’t have had to feel guilty about it. Lots of wonderful people have had it, you know. With the right medication, you could have led a perfectly normal life.” Academy Awards have notoriously been tilted at times towards feel-good performances by characters labouring under handicaps.

There is no “problem” here of such simple dimensions, unless one begins with a bourgeois norm, departures from which are considered pathological.

Emily Dickinson belongs with figures like Emily Bronte, and Van Gogh, and Rimbaud, and Hopkins with respect to an intensely heightened mingling of the micro and the macro—the super-sharp local particulars and the, for want of a better word, cosmic consciousness. And with her the intensity went further and the world was more fragmentary and strange. Her constant lovely use of metaphor and personification in both letters and poems is that of someone for whom, as for children, the animistic world has not yet been tidied up into dictionary-definable units with fixed boundaries.

But obviously in some instances of creativity, as with Van Gogh, there are chemical imbalances, at once blessing (in the heightening of perceptions) and curse, the body being liable to be light-sensitive (Emily’s references to her own “condition” are mostly to her eyes) and to have a curious collection of migrating ailments, at one point the eyes, at another digestion, at another migraines, at another a touch of arthritis perhaps, with medications having odd effects.

I have known personally two gifted and intelligent women artists of whom that was the case, and obviously they drove conventional doctors crazy, because unable to come up with clear diagnoses and cures.

In Martin Woodhouse’s excellent thriller Tree Frog, the hero, Giles Yeoman, is rendered unconscious and comes to to find himself stretched out in what is nominally an unmanned plane, with instructions coming in through the radio from his Machiavellian masters engaged in a deception operation.

In front of him as he gazes down at the desert through a clear-plastic square, is a small control stick with which he is expected to put the plane (at present on autopilot) through spectacular manoeuvres. When he takes control and tries for a gentle downward glide, the plane immediately nose-dives. The makers of it, be reflects, had made the controls too sensitive by a factor of ten.

Too sensitive by a factor of ten obviously applies also to Emily Dickinson.

XXXV

In 1869, Higginson wrote to her:

Sometimes I take out your letters & verses, dear friend, and when I feel their strange power, it is not strange that I find it hard to write & that long months pass. I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that perhaps if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkle of light.…

It is hard [for me] to understand how you can live so alone, with thoughts of such a quality coming up in you & even the companionship of your dog withdrawn. Yet it isolates one anywhere to think beyond a certain point or have such luminous flashes as come to you—so perhaps the place does not make much difference. (II, 461)

That feels perceptive—and admonitory when it comes to dealing with her even now, at least if one aspires to “understand” her. Looking at her letters to John Bowles, I wonder if, ironically, she didn’t become even more elusive when writing to someone whom she believed did understand her and could instantly grasp her obliquest allusion, Bowles must have been simply baffled at times.

But she probably had no trouble chatting with Maggie, her family’s Irish cook and maidservant.

Given all the lacunae and unknowables, and the impossibility of closure, she will no doubt go on inviting like Shakespeare, that particular favorite of hers, the attention of quasi-fictionalizing problem-solvers.

She is too often elusive for me too, when she isn’t, as in her later years, enunciating versified platitudes. She can be simply too abstract, and not just because dealing with affairs of the spirit that are beyond my own comprehension, but for the good of the poems when judged as poems, and not as pieces from the tissue of her life.

XXXVI

But Alfred Habbeger has the necessary sensitivity, empathy, and tact, and My Wars Are Laid Away, by virtue of providing a great deal of information without over-generalizing, is a convincing-feeling narrative of a remarkable life, at times edging into a disturbing disconnect, but in general an extraordinary working-through of problems that would have destroyed a lesser talent and weaker character, and with, especially after the dying down of that outburst of major creativity in the first half of the ’60s, a serious sympathetic interest in the lives of others.

Unlike Gordon’s book, it is not an easy read. There is too much of life’s complex realities in it to be controlled by the kinds of master formulae that make books skimmable and allow you to move on, after a few days, to some other book on the best-seller list to talk about at parties.

My Wars Are Laid Away is actually of little relevance to Dickinson’s best poems. To deal with those, you still have to think of them as poems, not as slices from a poet’s life. The ones that Habegger quotes are much more the equivalents of journal entries. But it is a moving trip through the life of a remarkable spirit, and a splendid example of what can be achieved in the holistic approach.

And yes, you can indeed see why people fall in love with her as she appears in so many of the lighter prose quotations.

How could one not, at least at a safe distance, love the writer of passages like the following, culled from just a short stretch of her life?

[Of her parents.] “They are religious—except me—and address an Eclipse, every morning, whom they call their “Father.”

[To Higginson, April 1862, Letters, II, 404]

Perhaps the whole United States are laughing at me too! I can’t stop for that! My business is to love. I found a bird, this morning, down—down—in a little bush at the end of the garden, and wherefore sing, I aid, since nobody hears?

One sob in the throat, one flutter of bosom—“My business is to sing”—and away she rose! How do I know but cherubim once, themselves, as patient, listened and applauded her unnoticed hymn?

[To Mr. and Mrs. Josiah Holland, summer 1862, II, 413]

When much in the Woods as a little Girl, I was told that the Snake would bite me, that I might pick a poisonous flower, or Goblins kidnap me, but I went along and met no one but Angels, who were far shyer of me, than I could be of them, so I hav’nt that confidence in fraud which may exercise.

[To Higginson, August 1862, II, 415]

The trees stand right up straight when they hear her boots, and will bear crockery wares instead of fruit, I fear. She hasn’t starched the geraniums yet, but will have ample time, unless she leaves before April. Emily [talking here about someone else] is very mean …

[To Louise and France Norcross, mid-October 1863, II, 428]

I was ill since September, and since April, in Boston, for a physician’s care. He does not let me go, yet I work in my Prison, and make Guests for myself.:

The physician has taken away my Pen.

[To Higginson, June 1864, II, 431]

Sorrow seems more general than it did, and not the estate of a few persons, since the war began; and if the anguish of others helped one with one’s own, now would be many medicines.

‘’Tis dangerous to value, for only the precious can alarm. I noticed that Robert Browning had another poem, and was astonished, till I remembered that I, in my smaller way, sang off charnel steps. Every day life feels mightier, and what we have the power to be, more stupendous.’

[To Louise and Frances Norcross, 1864? II, 436]

Then I make the yellow to the pies, and bang the spice for cake, and knit the soles to the stockings I knit the bodies to last June. They say I am a “help.” Partly because it is true, I suppose, and the rest applause. Mother and Margaret are so kind, father as gentle as he knows how, and Vinnie good to me, but “cannot see why I don’t get well.” That makes me think I am long sick, and this takes the ache to my eyes.”

[To Louise Norcross, early 1865, II, 439]

It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sundowns sterner, and Gibraltar lights make the village foreign. November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.

[To Elizabeth Holland, November1865, II, 444]

The lawn is full of south and the odors tangle, and I hear today for the first time the river in the tree.

[To Elizabeth Holland, May 1866, II, 452]

XXXVII

In his slim 1968 A Choice of Emily Dickinson’s Verse, Ted Hughes presents her in his introduction as a kind of American Sylvia—bright and sparkling at the outset, but becoming increasingly withdrawn. The cause that he sees is philosophical—the immense unknowability of the universe and her own small size in her engagements with it. In which, of course, though Hughes doesn’t make the connection, she belongs, very New Englandy, with Herman Melville, as Winters saw.

In this condition [says Hughes], there opened to her a vision—final reality, her own soul, the soul within the Universe—in all her descriptions of its nature, she never presumed to give it a name. It was her deeper, holisti experience: it was also the most terrible: timeless, deathly, vast, intense. It was like a contradiction to everything that the life in her trusted and loved, it was almost a final revelation of horrible Nothingness…

(xv)

I have trouble, though with seeing anguish in the outpouring of her verse, at least during the time of letters like those from which I’ve quoted. It would seem to me, rather, that there was an exhilaration in the bringing to completion, near enough, of so many poems during so short a time, in contrast to the metaphysical paralysis experienced by Mallarmé in the 1860s, and the effective silencing of Melville as a fiction writer after the debacle of the over-ambitious Pierre. And there is a vibrant poetic calm of spirit in the best poems, as distinct from the turbulences being talked about at times in them.

But Hughes’ selection is an interesting one, and I have to confess that, as may have been obvious already, there is indeed a lot in her thinking that I understand as little as did, maybe, Higginson.

Those damn dashes are firmly in place in this selection, though.

XXXVIII

In his account of her childhood years, Habegger writes:

Although it is impossible to quantify her school attendance, it appears she acquired much of her early learning at home, in the presence of a mother who spelled “feeling” with an “a”. Does that help explain why Dickinson began “upon” with an “o” for most of her life, or why she and her sister and brother never learned, or bothered with, standard punctuation? In Emily’s first letter, from age eleven, there are no periods or paragraphs and the “ou” combination in “would” and “you” looks like an “a”?

But he adds:

Yet the script is tiny, neat, and perfectly even, and, as we shall see in the next chapter, the composition is so fresh and fluent it is obvious the writer felt wholly at ease with a pen in her hand.

(99)

Franklin’s dashes, sort of like floating hyphens, look more like uncertain punctuation than the customary dashes. But they’re still needless distractions, and in other texts, such as Habegger’s, the dashes persist, giving us absurdities like, at the outset,

This – was the Town – she passed –

There – where she – rested – last –

Then – stepped more fast –

The little tracks – close prest –

How would readers like it if they were given:

A – slumber – did my spirit – seal–

I – had no – human – fears;

She seemed – a – thing that – could –not feel–

The – touch of –mortal –years?

As it happens, a recent Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson (Barnes and Noble Classics, 2003) is blessedly dashless. However, there are only about 575 poems in the volume, so the publisher’s use of the term “Collected” is baffling.

The most authoritative-looking normalized texts may be those in the University of Toronto’s magnificent Representative Poetry Online, where they simply take their place, unfussily, well formatted, and annotated, among the wealth of other poems there.

XXXIX

Lyndall Gordon’s book is readable, serves as a useful corrective, if one is needed, to the image of Dickinson as a pallid little whispery almost-nun, and is genuinely valuable, I would imagine, when she tucks Emily away out of sight and gets down to the torrid affair between Austin and Mabel (how did they ever manage with those clothes?) and the resulting family feuds, long-term in their consequences for finding, editing, and releasing into the print that never interested her while she was alive, Dickinson’s many handwritten poems and/or fragments (a distinction not always clear).

Our debt to Mabel Loomis Todd as research editor and enthusiastic Dickinsonian is obviously large, and Gordon is more at home with her than she is with Emily.

Her thesis about the epilepsy will probably catch on. No great exercising of the little grey cells is required for accepting it. “Oh, the medical evidence proves it, you can be sure of that.” (Incongruously, an image of Seinfeld’s Kramer’s head-nodding certitude comes to mind at this point.)

The worst thing will be when the idea of a lively Emily under something like house-arrest results in the TV establishment of her as a New England Miss Marples, briskly using her surplus energy to solve the mysteries of darkest Amherst, when brought to her by friends and relatives, without ever stepping outside the family compound; while, with a little adjustment of dates, Austin and Mabel are heating it up behind suspiciously closed doors as poor wife Susan broods upstairs in her room and common-sense Oirish Maggie keeps the wheels turning for them all.

Come on, it’s a natural.

Far better for a series than Wuthering Heights.

September 2010