Vincent van Gogh, Harvest at La Crau

Arles

I

I must add a fourth place—Arles. This was not a simple matter of romantic art associations. In 1967, we spent a month in an apartment in Cézanne’s Aix-en-Provence and were bored stiff.

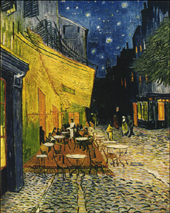

Of course it mattered very much that Arles was Van Gogh’s town. When we first went there in the summer of 1962 we went around looking at what he had seen and painted. We identified where the yellow house had stood, identified where the outdoor night cafe had been, walked to the chapel at the end of the Alyscamps, tried to find where the drawbridge had been, took a bus through the Camargues to Les Saintes Maries de la Mer, took the all-day bus tour that took us through the Crau and to the asylum at Saint Rémy, where we prowled and found the room that Van Gogh had had, and looked through the barred window at what he had seen and painted.

But it wasn’t a sentimental piety that kept us going back to Arles. We simply loved being there.We must have gone back four or five times, and it was better each time.

II

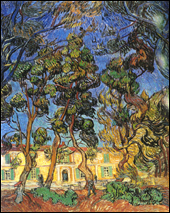

Van Gogh’s part of the asylum, when we went out there again, had been tidied up and closed to visitors—restored, I imagine, to its proper function. That didn’t matter. We had already been in there on our own, prowling through the overgrown garden with dried-up fountains where he had walked and drawn and sat on the stone benches.

The building had been used as a German barracks during the Occupation and hadn’t been tidied up. There were German words on the walls—Achtung, etc. There was a crudely drawn sign and arrow pointing along the corridor: Van Gogh’s room. And another scrawled word or two outside the room itself. On the way back along the corridor we came upon a broken-down, straight-back Provencal chair keeping a door open: Van Gogh’s chair, I mean the same kind of chair. I photographed it.

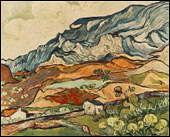

The asylum was not a museum or a shrine, it was a functioning asylum, one part of which hadn’t yet been put back to work. We stood in the gravelled drive by the main part and looked through bars and perhaps a bit of a hedge at old ladies walking slowly about, or standing still, in a gravelled yard. We looked at the twisted configurations of the Alpilles that Van Gogh had looked at and painted. When we looked out through the bars of his room, C. pointed out how we were looking at the exact configuration of his dramatic painting of an open field and a wall, with the Alpilles in the background. It was all there still.

This was a place where one could be mad and have a refuge, we hoped not just a prison. One could be in torment inside one’s head, but the place felt essentially benign, with the garden, and the Provencal sky, and olive groves, and fields, and hills. I talked with C. afterwards about how a documentary movie maker who had intelligently studied the movies and interviews of Georges Franju could do a moving documentary about the place.

III

Arles was a city that was functional, changing, organic, not ossified like the dreadful Aix, with its stiff neo-classical facades and ruler-straight main street, the Cours Mirabeau, with expensive prim cafes on the sunny side.

Every straight line in Arles changed direction after a short while, and there were very few perfect right angles. Spaces curved and flowed into each other. Even the longest street, the Boulevard des Lices, wasn’t straight and had comfortably large and plebeian cafes on it, in one of which, along with the entire clientele, we watched one of the great World Cup soccer matches. The wonderful long weekly outdoor market was in that street, too. The busses that took us to the places I’ve mentioned left from that street. In Van Gogh’s time it was where the coaches had left from.

The city was two thousand years old. It had been at the centre of a region then, it was at the centre of one still. And it wasn’t a museum. The Arena was being used for bullfights, with posters up outside it. The fragment of Roman theatre was tucked away unostentatiously, with lights and wooden structures indicating that it was still being used for theatrical purposes. Two of the inexpensive hotels that we stayed in must have dated back to the 17th century, if not earlier, and looked in places as if they’d been put together in a free-form way from stones taken from other buildings—perhaps from the Arena before it was considered a valuable antiquity.

In our favourite square, the Place du Forum, part of a Roman building had been incorporated into the facade of what was now a hotel. Van Gogh’s night cafe had been in that square, and its centre was occupied with cafe tables, chairs, sunshades. We sat there with the other tourists, a number of them Germans, and drank our pastis and our coffees. Another continuity.

IV

Obviously there were intelligent controls now on the kinds of changes that could go on, but changes did go on. One year the Place du Forum was awash with the sound of cars and motorbikes. Subsequently part of it was closed off to traffic. A street, leading off from another square and lined with shops was also closed off after awhile. There were some pretty fancy shops in it, though it ended up in a square a good deal further down the social ladder.

Down by the river, a building had been remodelled so as to contain an art cinema and a first-rate, Parisian-type bookstore. There was also, I think, a school of photography in the city. In the summer there was a music festival.

But though tourists, both French and foreign, were catered to—and it’s very nice to be catered to—C. and I could still stay in our surprisingly inexpensive Hotel du Musée, with its impressive stairway, and on one occasion treat ourselves for not much more than a normal room, to a huge high-ceilinged room that must have been one of the principal chambers when the building was still, in the older sense of the term, a Hôtel. We could walk a couple of blocks to a moderately priced prix fixe restaurant whose clientele were largely local, and go walking around the town at night along shuttered streets that must have looked much the same a hundred years before, when Van Gogh walked there, and a hundred or two hundred years before that, though no doubt darker and dirtier and perhaps less safe.

The Rhône, the great waterway, still swept silently past, as it had done hundreds of years before when Arles was one of the great trading towns. The city hadn’t been given meaning by Van Gogh’s having been there. It had had meaning long before him, and we, like him, were sharing in its calms and energies. (Yes, I’m well aware that parts of the city were much rougher in his time, and other parts probably stiflingly genteel.)

V

It was a city of contrasts and unintimidating fragments, the present going about its business among fragments from the past. Like Van Gogh, we responded to the strangeness, perhaps the mild sadness, of the Alyscamps, that tomb-lined avenue that was in fact only a fragment of the great Roman cemetery. But we weren’t particularly interested in its history. It was simply another bit of the Old, a place of odd shapes where occasional visitors walked, just as Sunday citizens had walked in his time.

We enjoyed the very different flatness and pastoral-bucolic tones of the Camargue, where horsemen, though we never saw any, herded the bulls that were used in bullfights. We enjoyed the way one suddenly came to the sea, even though now there were holidaymakers, a lot of them French, and not the fishing boats that Van Gogh drew and painted.

We were thrilled, though he hadn’t known about it, when one day we noticed a sign in one of the Arles churches saying that there was a crypt, and we paid a few francs to go and see what we assumed would be fragments of statuary, and went down, and passed through the crypt, and found ourselvs in a vast vaulted underground area that I think had been built by the Romans for storing wine and oil and corn, or maybe just corn. What mattered for us was the sheer vastness of this space down there that we and no doubt all but a handful of other tourists had walked over daily in utter ignorance of its existence.

Arles was a place of human shapes and spaces, often odd ones. It was a place that met a variety of human needs.

VI

The last time that we were there, we were out walking at night through some modest residential streets, perhaps pre-WWI, on the opposite side of the main street from the body of the town. Suddenly a puzzle solved itself.

We had speculated from time to time over the years about where Van Gogh had been when he painted one of his greatest paintings, the view of the town across fields, with irises in the foreground, and trees and red roofs in the background. I had been quite dogmatic about it, and quite wrong. Suddenly we saw two church towers, and they were the towers (we confirmed it afterwards), of the painting, and we were pretty well where he had been on that occasion when he “saw” something that spoke to him.

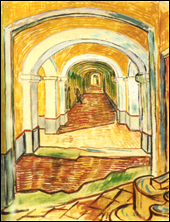

On another occasion, a street door or pair of doors was open and we found ourselves looking straight into another of his paintings, a courtyard or garden with a gallery or arches around it.

C. did almost no drawing in Arles. She didn’t need to. But on our first trip she sat and sketched outside the asylum at Saint-Rémy, and the first oil that she did of Provence came from that.

Vincent van Gogh, Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries