Found Pages: The Remarkable Harold Ernest (“Darcy Glinto”) Kelly, 1899–1969.

Sidebar 4: Deep South Slavery

I

Darcy Glinto’s excellent and not in any way exploitational novel Deep South Slave does not exist.

I myself own a copy, a Robin Hood Press paperback dated 1951. But the only mention of the book that I know of is Allen J. Hubin’s listing of it as a Glinto in his monumental Crime Fiction II, rev. ed. A Comprehensive Bibliography, 1749–1990, and neither I nor the research librarian Ian Colford have been able to find it listed in any library catalogue.

Nor is it in the English Catalogue of Books issued in Great Britain and Ireland, the series that lists a great many of the books published annually in those locales. Nor have I been able to find any reference to it, or to a book that sounds like it, in works about Southern fiction and Black fiction.

Darcy Glinto may not exist either, at least as the author of it. His name is emphatically on it. But the book is so knowledgeable-seeming about the American South, and the quality of the prose so consistently good, without analogies elsewhere in his work, as to leave for me, still, a question-mark hanging over it. If I were forced to choose, though, I would opt for its being indeed Glinto’s, or rather Kelly’s.

In the front of Deep South Slave we read:

While all the characters in this book are entirely fictional and every incident is imaginative and original, the author readily and gratefully acknowledges that the story was wholly inspired by John L. Spivak’s “Georgia Nigger” [Wishart & Company, London] That book, based upon a study officially authorized by the Prison Commissioners of Georgia, documented and photographically illustrated, is a piece of brilliant and courageous reporting which must move any reader possessed of humane instincts.

Its other principal chronological precursor is Robert E. Burns’ I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang, which appeared the year before Georgia Nigger and was filmed in the same year (1933) with Paul Muni not over-acting as Burns.

I will say a few words about both books before turning to Deep South Slave.

II

Robert E. Burns, I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang (1932)

A Northerner is sentenced to ten years on the chain-gang for his part in a robbery netting maybe a hundred dollars in today’s currency, escapes, lives respectably in the North for a number of years, is duped into returning by the promise of a brief token stretch of further servitude that will leave him a free man, and finds that he has to escape a second time.

The book is powerful and obviously had a major impact at the time, both as an exposé of Southern penal horrors and as another demonstration to the world of America’s dark side. However, it feels less four-square than it purports to be.

To me, at least, it gives the impression of having been written in installments by three different hands—the author’s slightly naïve and straightforward self, his more literary minister brother, and (for the second go-round in Georgia after he naively returns in the expectation of a quick release) a professional writer deftly maintaining suspense with the stops and starts and near-misses of Burns’ journey North, after setting out the details of the work-and-punishment system more methodically than before.

The second prison break feels a bit bogus to me. We have heard in detail about the chains and about the state of chronic and no doubt smelly filth in which the convicts lived, and then suddenly the narrator is running off to a waiting car and shortly afterwards, after changing into coveralls, goes into a small-town barbershop for a shave without anyone noticing anything odd about him.

The punishments, too, all seem to have happened to others. Was the narrator himself, short and initially unused to manual labour, never given the strap or hickory stick, or put in the appalling stocks and sweat-box? There is also some slightly odd stuff about mysterious forces (his estranged wife?) working implacably against him, and the incredible power of coincidence. Nor do we learn why the parole-board members never received the customary bribes that might have made a difference.

I would guess that bribery from outside came into the escape somewhere. But that would have been less heroic.

The editor of this reprint by the University of Georgia Press doesn’t mention Georgia Nigger in his introduction, and is obviously concerned to make sure that we outsiders (aka Northerners?) appreciate how offensive the book was back then to the pride of the sovereign State of Georgia.

He is also less indignant than one might expect about the curious later argument, countering the characterization of chain-gangs as “medieval,” that actually they were modern in their systematization of labour, and contributed to the construction of socially beneficial things like roads and bridges.

III

John L. Spivak,Georgia Nigger (1933)

The novel Georgia Nigger is a more satisfying work

John L. Spivak, it appears from Google, was a radical journalist who obtained letters of introduction from the Commissioner of the Prison Commission of Georgia that gave him entry to chain-gang prison camps. The guards seem to have talked freely with him, and he was able to take photos of important prison documents, such as death certificates and records of punishment, and of prison features like a fettered convict with ankle spikes, a convict in the infamous stocks, and another being agonizingly “stretched.” Twenty-six photos are included at the back of the book.

The story-line is simple. Young David Jackson, the son of Black share-croppers, is falsely accused of involvement in a brawl and has his fine paid by Planter Deering, who, with the connivance of the sheriff, obtains what is effectively slave-labour in that way. The work conditions are atrocious, an enraged Deering shoots an “impertinent” nigger before David’s eyes, and he runs away. Despite the help of one of the local gentry, he ends up on the chain gang, escapes, is recaptured, and we leave him back in a hell from which he obviously isn’t going to escape a second time.

The novel brings the awfulness of chain-gang conditions home to us with an immediacy missing from I Am a Fugitive. We are there in the foetid wheeled cages in which the prisons bunk at night, there in the stocks when the seat is knocked away from under us and we are suspended wholly by wrists and ankles, there with the lower part of our body bound to a post and the upper part strained horizontally by a rope that is then fastened to another post for an hour.

We are also witnesses to the bland legalisms of the bought sheriff, the false bonhomie of Planter Deering promising good working conditions, the voiced moral indignation about lazy and ungrateful niggers, the ferocity when thwarted (Deering again) that no-one can effectively call into question.

IV

But the novel, with its many individuated conversations, is a novel and not a political tract.

The wardens and guards aren’t simply whip-cracking monsters. Nor do the inmates constantly complain to one another, plot escape, and dream of freedom and justice. For the most part, they pretty well accept that this is simply the way things are, stoically endure pain, filth, and exhaustion and are pathetically grateful for occasional kindnesses from the Bosses. Likewise, the latter mostly treat their charges with a contemptuous good humour and, while mercilessly punishing their failinhgs, view those failings as simply what you’d expect from naturally inferior beings.

The novel achieves a particularly dreadful poignancy in Chapter XIV. The twenty-one-year-old Albert (Con) Hope, in the last stages of TB, lies on his bunk (with permission of the warden Bill Twine), his mouth filling with blood. The outside doctor, after being forced to come and look at him, says he’ll be fine, but the promised medication doesn’t arrive, and the doctor doesn’t return. (“Just keep him in bed an’ he’ll be alright,” he says over the phone.)

The flies rose from the congealing blood on the floor when the warden entered.

“How you feel now?”

“Pretty bad, Cap’n. Ain’ de doctor gonner come?”

“So he’ll come. Jes’ talked to him. Said fo’ you not to worry none. You’ll be settin’ a lively string [of cotton] right soon.”

Con’s lips spread in a ghastly grin.

“No, suh, Cap’n. I reck’n dis is jes’ about de en’ o’ dis here nigger.”

The terror behind his eyes belied the grin.

The Warden grunted and turned to leave.

But then Con asks for a preacher.

Bill Twine scratched his heavy jowls.

“I ain’t figgerin’ on you passin’ out but if you want a preacher, why I’ll git ol’ man Gilead down in town fo’ you. Sho I’ll git him.”

“Thank-ee, suh.”

“Git’m here in three shakes. Sen’ my Ford fo’m right now.”

“Thank-ee, suh,” Con repeated.

The warden sent a trusty.

“Bring’m back with you,” he instructed.

David himself is something of a cipher, though, with little in the way of distinguishing characteristics.

The book was published in England in 1933, and in other countries, and, like I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang, no doubt contributed to the British sense of a permanent American darkness below the Hollywood glamour and the aspiring skyscrapers—a sub-world dark, violent, cruel, evil.

V

Darcy Glinto, Deep South Slave (1951)

Deep South Slave, considered as a work of literature, is better still. As I have said, though, it has its puzzling aspects.

Simply put, did Kelly write it and, if he didn’t, who might have done so, and how could the Kellys have been able to use someone else’s manuscript (or pirate a published book), and if they did use someone else’s manuscript, how did they come in possession of it?

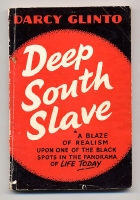

The book exists and a copy of it is on my desk as I write—one of the Robin Hood Press books, like Road Floozie and Ordeal by Shame. A large circular red patch, cropped at the left and right sides, occupies most of the front cover, with black above and below it and the title in large white script on it, slanting slightly upwards towards the right. Below it are the words “A blaze of realism upon one of the black spots in the panorama of life.”

On the back we have “6 Glinto titles you must read,” namely, You Took Me—Keep Me!, No Mortgage on a Coffin, Lady—Don’t Turn Over!, Road Floozie, One More Nice White Body, and She Gave Me Hell—and…

From the blurb on the inside of the front cover we learn that “Darcy Glinto with his sure instinct for throwing a blaze of realism on the black spots in the panorama of life to-day, sweeps away the myth that slavery in the States ended with the Civil War,” and that “This is a novel that sweeps along with all the power of Glinto’s consummate craftsmanship.”

Facing the title page we have, as “By the same author,” Road Floozie, You Took Me, and One More Nice White Body.

The tying of text to author could hardly be more emphatic, On the other hand, as I have also said, the book appears to have no existence in the British Library catalogue, the Library of Congress catalogue, or Copac. Allen Hubin, so far as I know, is the only person who makes the attribution in print.

VI

But if this novel was indeed by Kelly, where did the knowledge for it come from?

Not, that I can see, from Lillian Smith’s best-selling Strange Fruit (1944), or Don Tracy’s 1937 lynching novel How Sleeps the Beast, or even, despite the acknowledgment of indebtedness, from Georgia Nigger, or from I Am a Fugitive. By “knowledge” here, I mean the kind that enables one to be experientially there inside a landscape, or a social system, or the skins and speech-patterns of individuals very different from oneself.

Let me resort to a few quotations from the earlier chapters to show what I mean. The novel is quotable almost anywhere.

Here are a few words of the opening:

The Deep South. Georgia. Night time. Overhead the velvety depths of a near-tropic sky thickly spattered with stars that seemed as if a shimmering heat-haze hovered over them. As if the heat that enveloped everything there below had risen on and on until it filled the sky. (p.16)

Here is Planter Clay at work and play:

Any young negress who had caught his eye would find herself, a day or two after, sent on some errand that took her past some isolated shack when the rest of the niggers were out at work in the fields. Passing the shack they would see his big bay tethered behind it and he would be there in the doorway with a very different expression on his face to the one they all saw when he rode his rounds. He would be grinning now and there would be a genial brightness in his eyes.

“Howdy, Dinah!” He called them all Dinah.

“Howdy, Mis’ Clay, suh!”

“Kinda hot for a nice little nigger girl to be traipsin’ around, ain’t it?”

“Yeah, it sho’ is pretty hot, Mis’ Clay, suh.”

“You better stop by and rest a bit out of the sun.”

Most of them would know what this meant, what to expect and some of them would be very willing to stop. There was a kind of handsomeness to Planter Clay, with his tall, lean figure and his full, fleshy lips under the thick moustache. But whether she expected it or not, whether she welcomed it or not, any suggestion from his was an order. No nigger girl would dare disobey. (pp. 21–22)

Here is a crap game in progress in the Black half of the drug-store on the town square:

“For de Lawd’s sake, gamblers, don’t you have any dollars dese days? I ain’t playin’ all by my own self. It’s mah throw. Ain’t somebody puttin’ down somethin’ to make it worth a nigger’s while to roll his dice? C’mawn gamblers, if yo’ is gamblers, what de say-so. If yo’ aint here to speculate, what yo’ doin’ in a crap game at all? I never fancied this town had a whole lot of secret niggers, scared to throw down a coin to git some back. Yo’ is all safe. Ah knows this is mah unlucky day. Come out, yo’ gamblers, throw it down. (p. 48)

Here is Artemis, the most stylish and independent of the girls in the whorehouse of Nellie Devereux, that “mountain of black flesh” in whose perpetual wide grin “there was no real humour … and no kindness either in it or anywhere else in Nellie Devereux.”

If she had just been wearing stockings, and some small white frilly underneath, the only difference between her and the other girls from the waist down would have been that she showed more of herself more frequently. But what showed was not just stockings and dark skin. She had stockings. They were of black silk. But above them she was wearing a pair of old-fashioned drawers. They were of lawn and looked very white above the black stockings under the bright red of her dress, and they hung loose-legged almost to her knee and had a two inch wide frill of lace at their bottoms. Somehow it looked a lot more daring for a girl to be showing drawers of that kind with every movement she made, and although she had fine slim legs, they looked finer and slimmer showing sheathed in their black silk, below the lace fringe of those drawers. (p. 55)

Here is Joshua after leaving the prison camp, lying on the soft yellow grass near where he had first had sexual contact a few years earlier.

The hum of the insects was still like the simmering of a great boiler in the air around him and the ground beneath him. There were the inevitable sounds from the shacks, voices and the clinking of pans. Yet somehow it seemed that there was a quiet here, such as he had not felt for a long time. He thought about that and it seemed queer that it was real, and it began to have an effect on him. Some of the tension passed from his mind. He could leave thinking incessantly of that one year past and let his mind rove further back to when he had been gay and happy. (p.110)

Yes, I know, those are all “quality” passages that could perhaps be extrapolated from readings in fiction. (I seem to hear the Lawrence of The Rainbow in one or two places.) But there is also all the casual knowledgeability about a variety of individual Southern types, both white and black, in a variety of encounters, and about the district, and about the psychology of lynch mobs, and so on.

The narrating voice, to my untutored ears at least, feels Southern. The Black speech is more convincing than the Black speech in Georgia Nigger.

VII

Glinto? Kelly? I ought to be able to say by now, and there are lyrical passages in the Lance Carson Westerns. But the case seems to me unique.

There are chasms between Stephen Frances at his Janson worst on the one hand (I suspect it’s preponderant) and on the other his remarkably good 600-plus-page novel about the Spanish Civil War, La Guerra (1970) and the horrifying historical novel In the Hands of the Inquisition which appeared the following year over the name of Maria Deluz and had me wondering, before I knew the authorship, whether it could be a translation of something by some fin-de-siècle French writer like Jean de Villiot. Any literary critic worth his or her salt would testify under oath that they were by different hands.

But we know that the last two came late in Frances’ career after he had served a long apprenticeship, with flashes of real distinction along the way, such as in the narrative of the two American women cousins sent to a Nazi concentration camp in Women Hate Till Death (1951).

But when Deep-South Slave appeared in 1951, it was in a year with a Lance Carson Western in it, and two original Glintos the year before, and four original Glintos and a Carson the following year. It wasn’t as if Kelly had been off on a sabbatical.

VIII

And the book itself?

It is excellent—pulsing with life, moving, funny at times, heartening, not a downer, and still wholly fresh today, whereas a bestselling and at the time scandalous novel like Lillian Smith’s 1944 Strange Fruit (banned in Massachusetts) has faded into the grey limbo of leftish protest fiction.

Deep South Slave is a novel about the self-assertive energies of youth, regardless of skin-colour, the hunger for a due independence, the spirit of W.B. Yeats’s “And never stoop to a mechanical/ Or servile shape at others’ beck and call.”

And gradually it became known through the county that young Joshua Skellett was “one sho’ helamighty blade with the women.” But that made it all easier still for him and in turn made him more and more sure of himself. And because he was so sure of himself, because life was bringing him so many enjoyments in that direction, a new buoyancy came to him. He was always bright, with a ready grin and a quick remark after. His harmonica was more and more often at his mouth, and the gaiety of his playing was more and more infectious. Joshua Skellett became quite a character in the district. (pp.31–32)

Joshua’s risk-taking is the risk-taking of someone who simply doesn’t feel himself defined and constrained by the operative Southern conventions, and hence underestimates the power of the forces that come into play against him.

But those forces, at least the legal ones of Sheriff Connell and the judge who sentences Joshua to a year on the chain-gang for his alleged participation in a gambling fracas, aren’t caricatured.

As Glinto explains in another of those passages of informed analysis that nag at me, “The wealthy planters can get the law leveled or the law in their pockets so that the sheriff and his deputies are their servants first and the servants of the Legislature afterwards.” The planters, producing as they do “a substantial section of the nation’s wealth,” are able to “affect the training of the law right at the highest level in Washington,” where “their spokesmen can sit in the Senate and build up a pressure group powerful enough to drive the law-making machinery its way.”

But between those highest and lowest levels, there is the law proper and the men who administer it. To these men law is a profession and with some of them it comes near to being a religion. You cannot buy judges whatever some of the top-sale fiction writers may do with judges in their books. A judge would have his price the same as any other man. But because the law is so much his life, the only price he would sell out for would be a better law than the one he knows now. (pp. 97–98)

And Sheriff Connell, despite having had to accept the false words of witnesses about the fracas, behaves honourably and humanely as the fury of the lynch mob mounts after Joshua, back from his year’s imprisonment, is accused, with all-too-plausible-seeming evidence, of raping a white woman, his first inamorata, white-trash Ella Timmins, whose jealousy had been responsible for his being framed in the first place.

IX

Nor are the appalling, the truly monstrous, details of chain-gang life at that time as detailed with evident accuracy in I Am a Fugitive and Georgia Nigger milked here for effect.

There is a page-and-a-half about how Joshua, a turbulent prisoner, was punished at various times with the stocks, the sweat-box, and “stretching” (which must have induced agonizing cramps). The information presumably comes from Georgia Nigger, though Spivak doesn’t achieve the kinesthetic immediacy of a sentence like this about the sweatbox: “As they shut him in they drenched a bucket of water over him, so that with the rising heat, steam formed, and the half vitiated air felt like strips of blanket being dragged in and out of his lungs.”

But basically Glinto cuts from the end of the trial to Joshua’s release, and the only other appearance of the horrors is when we read:

Walking along the dusty road, just released from the prison camp a year later, he was not only a grown man but a man with a set slouch in his movements and a bitterness in his expression which said that his boyhood was far behind. He had reached his full height now, but the easy swing of its movement had gone. There was something oddly awkward, too, in the way he walked. He held his legs too wide apart.

Glinto comments: “Anyone who knew the prison camps of the South could have explained that walking with the legs apart. It came from wearing the cramping spike shackles that were forged on to the legs of violent prisoners.” According to Spivak, the spikes for one leg, which evidently looked rather like pickaxe heads, measured about two feet from tip to tip and weighed twenty pounds.

X

The continence and humanity of the writing bring to mind B.Traven’s when explaining the technically legal workings of the slave-labour system during the Diaz regime in novels like Government (U.K. translation 1935), and make the book all the more telling as a protest against servitude of any kind.

But niggers are not born for the purpose of enjoying their lives—not as the white planters see it down here in the deep south anyway. A nigger is a working animal, like a horse. Maybe he is not so important as a horse and doesn’t have to be looked after as well. His moods don’t have to be allowed for, and he never needs to be coaxed along. The thing to do with a nigger is to fix him on a cast-iron contract, fake the running of the contract so that it never ends while the nigger is alive, and then drive him to the limit. Nothing of all that is written into the constitution and law of the United States. But it is practised into the law of the Deep South States, and what is practised into the law is part of the constitution for all that any nigger can do about it. (p.32)

(The phrase “down here in the deep south” and the American spelling of “practice” might invite pondering.)

The book is also erotic without being in any way pornographic, insofar as there is a distinction there. Here are Joshua and (white) Ella Timmins after his release from the work camp:

Lying there with Ella now, he was merely going through the old motions instinctively. Perhaps the long denial was resulting in a greater intensity, but it was the difference in his strength that Ella was suddenly, painfully, yet ecstatically aware of. The pressure round her was all but unbearable, perhaps would have been quite unbearable if unexpected gratification after the long denial on her side had not made her glory in it. The grip was so powerful that it seemed to suspend every inner activity within her body. She had to stop breathing and then it seemed even as if her blood had stopped flowing. At first there was a surging sound in her ears and a rushing sensation in her head. But then it seemed as if she was floating away from all around and she all but lost consciousness. Maybe it was the sudden slackening of her body that made Joshua relax his grip. She took a long, sighing breath then, and a sharp spasm went through her body, and her head dropped over to one side in complete abandon as his hands moved [removed?] the cotton dress. (p.116)

Deep South Slave belongs with Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, (1937) rather than with Richard Wright’s overrated Native Son (1940). It feels “Black.”

XI

It would help to know if Kelly had ever been in the American South even briefly. The simplest explanation, after all, would be that, energized by Georgia Nigger, he made a research trip there. Edgar Wallace apparently derived On the Spot from twenty-four intensive hours in Capone’s Chicago, and Kelly, who had been a freelance journalist in the Twenties and Thirties, could presumably pick up information fast.

The attitudes in the book certainly fit with what we have seen of Kelly’s in general, and Deep-South Slave could have been a riff on Spivak’s book the way Lady—Don’t Turn Over had been on Chase’s.

Such an explanation is certainly preferable in human terms to the appropriation by the Kellys of someone else’s unpublished or obscurely published novel in the certain knowledge that it would mean a third lost court case were the defrauded author or the author’s heirs to sue, not to mention the dishonorableness. This was the Robin Hood, not the Jolly Roger Press.

And if the manuscript hadn’t been published before, why could it not be over the author’s own name? Sarah Prentiss’s novel Ordeal by Shame appeared in the same year, with the same kind of front cover and the words “Darcy Glinto introduces” so prominent upon it that at a first glance you assume that it is by him.

The book would still have been a remarkable feat of self-transcendence. But so were Stephen Frances’ La Guerra and Edgar Wallace’s On the Spot in relation to the general run of their work, and Ted Lewis’s Jack’s Return Home (1970) in relation to All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965). For that matter, would anyone have predicted a Great Gatsby on the basis of This Side of Paradise?

So, did Harold Ernest Kelly write Deep South Slave? The alternatives being so out of character, I’m going to say Yes. I don’t know how he did it. But the had several styles at his disposal, and the the distance between the best prose of the best Westerns and that of Deep South Slave isn’t large. It would still be a remarkable achievement, though.

Deep South Slave and Georgia Nigger both strongly deserve to be reprinted. But Deep South Slave would be as literature and not as, primarily, an important and at times moving social document.

Sidebars:

- Sidebar 1. Some Orchids

- Sidebar 2. Chase and Glinto

- Sidebar 3. The Pre-trial Glintos

- Sidebar 5. Darcy Janson

- Sidebar 6. Rogues’ Gallery

- Sidebar 7. Kelly Brothers

- Sidebar 8. Scandal

- Sidebar 9. Westerns

- Sidebar 10. City Mid-Week

- Sidebar 11. Gangdom

- Sidebar 12. Jungle Books

- Sidebar 13. Bodily Harms

- Sidebar 14. Propaganda?

May 2006