Cogitations

An Educated Imagination: Carol Hoorn Fraser, Artist

A lecture about the artist Carol Hoorn Fraser at the University of King’s College, Halifax, Nova Scotia, April 11, 2008: the final lecture for the year in the King’s Foundation Year Programme.

This, with excisions restored, factual errors corrected, points clarified, and stylistic tweakings, is a firmed-up version of the lecture that I’d imagined myself giving.

Fortunately, as the hour-hand on my clock advanced inexorably, I started skipping and winging it, and eventually was simply presenting image after image up there on the big screen, with informal comments.

What I had envisaged would soon have been quite at odds with the festive close to what had obviously been a fabulous educational year for some three hundred University of King’s College freshmen.

But I still managed to fit in, one way and another, most of the main points that I had wanted to make.

The material that I didn’t get to present still seems to me relevant, though.

A number of the key works that I mention are in “Gallery,” on the Carol side of Jottings.

For more about her, see the Carol side of this site www.jottings.ca/carol and www.thistledance.com.

For the King’s Foundation Year Programme, with its year-long, walls-down guided journey through key texts and topics in Western civilization from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen, see http://www.ukings.ca/kings_2900.html.

This was my own first contact with it.

Prefatory

President Barker, ladies and gentlemen.

It is a pleasure and privilege to be here today addressing such an audience.

Sixty years ago, at the age of seventeen, Carol Hoorn entered the Swedish-American Minnesota college Gustavus Adolphus, to which her Lutheran minister father had gone before her.

If she’d been magically teleported and offered the chance to enter the Foundation Year Program, I think she would have been thrilled, though doubtful of her ability to keep up.

She was a slow reader. But she had a very good mind, and what one of the In Cold Blood killers said of the other to Truman Capote applied to her. “When that boy reads a book, it stays read.”

And she became a humanely educated artist.

This talk touches on the rewards and perils of an educated mind, an educated creative mind.

What’s coming

Pat Dixon’s choice of an image to announce this show, “And All the Trumpets Sounded”, was excellent, and I shall end up with it. VIEW

But I don’t want to engage in an elegiac love-in today. I want, rather, to introduce some broader principles and perhaps forgotten facts, not all of them happy.

I will be selective, but there’s lots more about her and by her on the Web, and I’ll put a couple of URLs up on the screen at the end.

I had no privileged entry into her works. She never told me what she wanted to achieve in her career, or what a work “meant.”

But I did know the circumstances under which some of them were created. And we talked from time to time about art.

During the middle part of today’s performance, I will be telling but not showing. Then, by way of compensation, you will have a lot more images to look at. One way and another, there are almost a hundred.

During the past several days, since accepting this assignment, I’ve felt a bit like a dormant old bottle of domestic champagne that has been abruptly shaken and uncorked.

There’s so much to say that I fear there may not be time for questions. But since in the latter part you will be looking at images by her rather than listening to me, I hope you will feel that it’s a reasonable trade-off.

So, off we go.

Picasso and selves

The dumbest remark I ever made in print was when I said that if I had to choose between saving the works of the great photographer Eugène Atget from oblivion and those of Pablo Picasso, I would unhesitatingly choose the former.

I loved Atget and wrote a well-received article about him.

But I had a simplistic image of Picasso’s line of development in my head—melancholy blue stuff, cheerier pink stuff, brown cubistics, something called neoclassicism, and, pow, the jagged Picasso of “Guernica” and after.

What I didn’t know was the near-simultaneity at times of his family of styles.

Here is quintessential Picasso, his iconic “Weeping Woman.” VIEW

But if you weren’t told, would you think that this girl on the beach was also his? VIEW

Or this delicately pensive penciled face? VIEW

Or this girl wearing a chaplet? VIEW

All four are from the same few months and give us the beautiful, gifted, tragic Dora Maar.

Faced with a pattern so vastly different from the stylistic continuities of an Edward Hopper or an Alex Colville, what do we say?

Is the “real” Picasso the aggressive Picasso of “Guernica”, who’ll occasionally be nice when it suits him?

Or alternatively, is the tender Picasso the real one, masked by the other’s theatrics?

Neither, surely.

Look, here he is in 1937, with Dora herself, whose brilliant photographic career he put an end to—apart, that is, from her photographing him. VIEW

We see the Picasso gaze, the famous gaze that he turned on such a variety of subjects, materials, possibilities.

And we sense the Picasso mind.

Not just “mental”

But not just a “mind,” brilliant though his was.

And he’s not just making “Picassos” in these works, expanding his self-image and demonstrating that, yes, he can too draw.

Or doing a series as a series—the Dora series—as distinct from doing individual works that, collectively, are a series, but not a sequential one, one image leading to the next.

No, there’s a “grasp” here, an intense and intent reaching out that is at once physical and mental, reaching for Dora (for a variety of Doras in different moods, hers, his).

It is the same primal art impulse as we see at work over 20,000 years ago in the wonderful, taut, hunting lions, and other animals, on the walls of the Chauvet Cave. VIEW

And the distortions in “Weeping Woman” are three- dimensional and expressive, not mere designing or free play.

We feel her wretchedness.

Some of this, we will find, was true of Carol.

And I want to walk us through, though not in strict chronological sequences, some key aspects of her character and career.

Carol and selves

First, some reminders of the differences between an artist’s social personality, such as you’d encounter at the vets’, or in the produce section of a Super Store, or at a party, and more inward movements of what used to be called the soul but which I’ll call the mind.

For a good many people now, unless they’ve gone to the Web, Carol Hoorn Fraser is likely to be the Carol of the lovely watercolor greeting cards put out by Thistle Dance Publishing, including “And All the Trumpets Sounded,” that you’ll see on racks around town.

So here, photographically, is a possible creator of those.

While she still had long hair. VIEW

Holding the lovely old one-eyed cat “Raghead” who adopted us during our two Provence summers in Seillons-Source-d’Argens. VIEW

Being very nice. VIEW

After sampling an interesting medicinal herb that a friend had brought back from the Far East. VIEW

[Laughter.]

Older (taken by a professional). VIEW

But there were other Carols.

Here are suffering selves.

Unhappy behind our Minneapolis apartment building. (That one was early in our marriage, so she had good cause to be unhappy.) VIEW

Too gaunt among trees. VIEW

Tense in a self-portrait. (A doctor diagnosed migraine in that one.) VIEW

Here are a couple of assertive selves.

Imagine that hat turned loose on society. (I think a student of hers took the pic.) VIEW

Or that leonine figure. VIEW

And this early woodcut, “The Voyage,” may answer to a more inward sense of herself on her shoestring first trip to Europe, or more fundamentally. VIEW

Here, finally, is the creator.

I love this one from student days in Minneapolis. VIEW

Here she is in the first summer of her Halifax garden. VIEW

Her garden obviously became process art, an intersecting of types of flowers, growing seasons, and sun-catching or avoiding beds, where nothing ever went quite the way it should.

Here she is, more pensive, my best photo of the artist. VIEW

She smoked for twenty years and had great trouble quitting.

It shortened her life. But we all smoked back then.

Matching images

So, now a quick matching of images.

Here are some “nice” ones from the cards.

Here are our pussies—Joey, Annie, and Shinski. VIEW

These images are what, if you didn’t know her work, you might imagine the “nice” Carol of the photos to have been making.

But now, what about these ones? What might the maker of these have looked like? Or been like.

I think of this one, “Couple II,” as her “Guernica” of the sex war. VIEW

And with “Major Surgery” it’s virtually horror-movie time, isn’t it? VIEW

She did in fact enjoy horror movies, but ones about psychological marginality, rather than gorefests. She felt for figures like Peter Cushing’s obsessed Dr. Frankenstein, Christopher Lee’s Byronic Count Dracula, the spore-infected returned astronaut in The Quatermass Experiment, the circus people in Tod Browning’s Freaks.

When we came out from Georges Franju’s masterpieces, Eyes without a Face, about skin-grafting, and I called it the most unpleasant movie I’d ever seen, she said no, it was poetic. Which sent me off along a whole new track.

She felt deeply for the late-Victorian Elephant Man, so-called, hideously deformed but amazingly sweet-natured—felt too deeply, I judge, to want to incorporate him into a painting.

Here is “Head Wound,” for me her most brilliant oil. I shall be returning to it. VIEW

“Revelation” isn’t literally a self-portrait, but probably contains an inner truth. H.D.’s poem “Orchard,” which I’m sure she knew as a student, says, “Spare us from loveliness…/ You have flayed us/ with your blossoms.” VIEW

“A Taste of Honey” would be sweet, you’d think. But what a sinister blind muscle that tongue is, thrusting out from its hard-edged cavern! VIEW

There was obviously a bigger disjunction in Carol between the social self—cat lady, gardening addict, giver, for awhile, of delicious dinner parties—and the fiercer inner creative self than in the Picasso whom we glanced at.

Bigger too, perhaps, than with a number of other female artists. I don’t imagine Frida Kahlo scoring high on the niceness end of the scale.

The great 1977 show

But, having pulled things apart, let me now bring some of them closer together.

Those “difficult” paintings were in the great 1967–77 retrospective at Dalhousie, curated by Mary MacLachlan, in close consultation with Carol, which filled the Dalhousie Art Gallery.

It was a marvelous show, a plenitude—28 oils, 25 drawings, 19 coloured inks.

Among them was a very different car, a very different heart, a very different couple.

The dumbest thing I ever said to her about her art was suggesting that “The Journey South” would be better without the female figure in the glove compartment. VIEW

The painting of that big open heart in the woods was called “Valentine with Love to Christiaan Barnard,” who had done the first human heart transplant, a title that still puzzles me. VIEW

We’ll be returning to “Grandparents 1.” VIEW

There were paintings like “Inland” and “Solipsist.”

“Inland” took off from a poetic documentary, Le Corps Profond (The Deep Body), that we’d seen in Paris in the early Sixties. It consisted of images taken by tiny optical tubes or cables traversing the interior of the body as if it were a cave system. VIEW

“The Solipsist” registers an allure, I think, that she resisted, lovely though the interior monologue of a self feeling an erotic merging with an unthreatening nature could be. VIEW

And the major oils were almost all different from one another. There was something in her of what André Breton said about René Magritte when he spoke of a

unique and harsh enterprise, at the confines of the physical and the intellectual, and bringing into play all the resources of a mind so exacting as to conceive each picture as the occasion to resolve an entirely new problem.

Down there in that windowless gallery, with its different areas, was like being inside a wonderfully rich and varied mind.

It was a mind way beyond that of the social individual who brought me my morning tea in bed, and fussed over destroyed flowers in the garden.

Or even the person who had shown me most of the various works separately.

Now the daily “she” wasn’t speaking. The pictures were.

Now there was simply a wonderful set of interanimating explorations.

Drawings

What especially interested me, and held me riveted each time I returned, were certain drawings, namely “Complacency” VIEW, “Hybrid Study” VIEW, and “Squash Blossoms” VIEW.

They seemed thrillingly to suggest new possibilities, open new doors, initiate a new phase, a moving on.

They were remarkable for their freshness of invention.

They were all done around that time.

The show meant a lot to her.

She’d had six years of poor health, isolation, and deprivation.

Her genial friend Doug Shadbolt (brother of artist Jack), who’d headed the School of Architecture at T.U.N.S., had left at the start of the Seventies, along with his wife Sidney, another friend.

Under the bottom-line, systems-oriented new head, she’d lost the freehand drawing class for architectural students that she loved, a class aimed at helping them to see.

She’d have them draw a chair— draw it without looking at it—draw it, without looking at it, upside down and from behind.

She ran the annual sketch camp—ten days of intently drawing buildings and streetscapes in some small Nova Scotia community. (She said she was glad there was no nonsense about their making Art, but some of the sketches looked pretty good to me.)

She’d begun giving the class in 1963. In 1967–68 she also taught an introductory art history class there.

Losing her role and status at T.U.N.S. had hurt.

And now, blessedly, the recognition implicit in the Dalhousie show started her energies flowing freely again.

But in fact no doors opened

Reactions to show

The show traveled, as planned, to seven other provinces, including BC, Ontario, and Quebec, and one way and another, various pictures in it were sold.

But it received exactly five reviews. We waited in vain for more.

Three of them, friendly ones, especially a long and knowledgeable one by the artist Felicity Redgrave, were in Maritime publications.

The fourth, for the CBC by a youngish local artist, announced nationally that the works were born out of “nightmares,” the technique was incompetent (she wanted to take her brush and finish pictures up), the catalogue was pretentious, and the show left her feeling “nauseous” and “very upset.”

This was while the show was still in Halifax.

The ArtsCanada review, the one that really counted, was a largely unfriendly half-page affair with one illustration. The reviewer observed that “the paintings are more or less generously embellished with a variety of symbols of doubtful artistry and relevance.”

Our local reviewer, in what at that time was known as the Chronically Horrid, gave it exactly three-and-a-half lines.

Interestingly, the respectful reviewer for the Daily Gleaner, Fredericton, found much of the work “frightening,” but also considered that “it is in no way depressing. One is left with a sense of awe at the human mystery.”

Interpretation

Now, it’s easy to say, as some friends did at the time, that she should have laughed or shrugged it off—that she was so good and known by, well, friends and admirers, to be good, that she’d outlast the carpers.

Like her particular hero Van Gogh.

But good things don’t happen “inevitably,” at least not during an artist or writer’s lifetime.

The discovery of the great French “primitive” Henri Rousseau was due in large part to the powerful intelligence and publicity skills of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

According to Wikipedia, shortly before dying, Rousseau told him, “You will unfold your literary talent and avenge me for all the insults and abuse I have experienced.”

Intelligence and taste are required, and the ability to communicate them, what used to be called connoisseurship, the kind that Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen displayed when helping the American nouveaux-riches acquire the art that later became the core of public collections. Such as the wonderful Frick Museum on Fifth Avenue.

Required—a creative, intently focused discerning, which entails proceeding individual work by individual work, rather than pigeonholing and finding virtue or the absence of it in everything by this or that particular artist. (Quality doesn’t travel by osmosis.)

And a generous defining of an artist by his or her best work, rather than averaging out as if dealing with a financial stock

And not being swayed by an artist’s actual or reported social personality.

The history of taste is complicated. But there truly is no substitute for taste and the ability to recognize quality. Which is not the same thing as cannily spotting trends.

And blindness is blindness.

The best African-American writer, Zora Neale Hurston, worked as a domestic in her final years and was buried in an unmarked grave.

The remarkable art of Bernice Purdy, now in her sixties and the most interesting Nova-Scotia-born artist, still remains to be discovered by our snobbish local art establishment.

Her “Burning Ritual” VIEW is sexy and funny. “Gus’s Pub” VIEW is a lovely warm celebration of gender differences comfortable together, with faces of a quality which you’ll look for in vain in current art ’zines. “The Hawk” VIEW was stolen.

Carol admired the ability of Berenson’s protégé Kenneth Clark to help you see a work. And ENJOY it. Not merely acquire a few phrases to “explain” it.

Break

In any event, the fact of the matter is that the momentum in those remarkable drawings, the promised opening up of a whole new range of images, was broken.

She virtually stopped making art for a couple of years. When she returned seriously to it, it was in a diminished mode.

For the point of such a pattern of reviews is that it signals that this particular artist is without clout, without protections, without any kind of shield, without anything that requires serious attention.

So, despite all the effort and intelligence that had gone into the work of that decade, there had been no breakthrough. She remained regional. And not just regional but, in some eyes, provincial.

She had had, I judge, a hunger for communication and sharing—as if, perhaps, she envisaged people, in front of this or that work of hers, experiencing it with the kind of pleasure that she herself felt in galleries in front of pictures that she loved or was fascinated by.

You will know, I’m sure, how the mind can flow and leap and surprise itself in free group discussions—and be numbed by authoritarianism and ad hominem polemics in others.

She carried on, after a bit, and her later career is a triumph of character and true professionalism.

And memorable art resulted.

But there were losses.

Provenance

So who was this Carol Fraser, the Carol Hoorn Fraser embodied in a variety of ways in that show?

A quick bio trip says that she

was the Wisconsin-born daughter of a Swedish-American Lutheran minister who died when Carol was fifteen, leaving his widow and two daughters penniless;

packed her two final years of high-school into one;

graduated in 1951 from the Lutheran Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota with a B.Sc. in chemistry;

worked for a year as a control chemist for the Archer Daniel Midland grain company;

went to Europe in 1952 for a year on $600;

was admitted on her second try, after make-up courses, to the MFA programme at the University of Minnesota;

worked for a time as a nurse’s aide in the terminal cancer ward in the university hospital, where she saw the results of “heroic” surgery;

did art therapy with mental patients.

Where did the great show come from?

It came from a rich, an enriched mind—an educated mind.

And one whose education had sharpened the creative self.

It hadn’t been muffled by the kind of teaching in which every work of art must be appreciated “on its own terms.”

Or stuffed with half-understood jargons whose use provides the illusion of being a coherent self with a mature “position.”

Or narrowed with a history of art’s irresistible Darwinian progression to the one right mode of art-making now.

The Carol Fraser who disembarked in Halifax in 1961 was an educated artist who carried a culture within her.

In Germany and at Minnesota, she had experienced the real thing.

Germany

During her months in Göttingen in the early Fifties she had stayed in Nansen International House, run by a practical German idealist, where young Germans and non-Germans mingled. She and a friend were the only two Americans there.

The Germans, she would say later in an interview, had been “probably the most significant, the most memorable people that I have ever met in my life—or ever will meet.”

There had been high-level discussions among them about major ethical issues in a still postwar-austerity Germany. Two or three of the Germans, Rainer Friedrich told me, later became active in the radical SDS, the Students for a Democratic Society.

And she audited lectures at the university by the eminent theologian Friedrich Gogarten.

She had a strong inner religious core, bringing texts by Kierkegaard, Tillich, Buber, Maritain, and Rilke with her when we married in 1956.

She also had an unusually strong awareness of and interest in the body, the enabler of our being-in-the-world.

If she could have afforded the training, she said later, she would have become a medical illustrator.

Minnesota

She became a star at Minnesota as an MFA student, winning prizes in prestigious juried shows at the Walker Art Center and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The critic-theorist Clement Greenberg, as a juror, praised the brushwork of her thesis painting. Canada’s Michael Snow was an also-ran in one such show. As was James, later Jim, Rosenquist.

She did a minor in what was one of the top Philosophy departments in the country, with a three-term course on “Problems of Aesthetics” from John Hospers, author of Meaning and Truth in the Arts, and a term on Kierkegaard.

She also took “Literary Theory” and “The Appreciation of Poetry” in the English Department from the distinguished poet-critic Allen Tate, her portrait bust of whom is in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, and wrote a jargon-free 126-page MFA thesis on “The Human Image in Contemporary Painting.”

She took several art-history courses. But she got most, I think, from assisting and pulling slides for the survey course of the brilliant Lorenz Eitner, an authority on Géricault, who later headed the Stanford Art Department, and who looked at her thesis in draft and helped eliminate what he called MFA prose—pretentious fuzzy overstatements.

She loved art history, loved the breadth and wealth and variety. It was exciting going with her through galleries.

And she had learned in Minnesota’s excellent programme the middle way of the mind between works as “texts,” all equal way-stations on a chronological line (“Rembrandt? Oh, that was the second week last term”) and temple deities before whom to prostrate oneself.

She had learned interrogating, dialoguing, intelligent appropriating, done with Paul Tillich’s “ultimate concern.”

She participated in and assimilated a tradition in which making a work of art, like doing a piece of writing, was a complex thinking-through requiring total concentration all the way.

Nourishment in Halifax

So, when she disembarked in Halifax in 1961, she wasn’t alone artistically.

These truly were the backwoods then—no non-commercial art gallery, only one commercial one, only one person teaching art history (at Dalhousie).

Plus an art college, up on Coburg Road, where the Principal rang the bell each morning for prayers and the young ladies wore dresses and heels to class and didn’t, she told me incredulously, know how to construct a colour wheel. Which I assumed would be like a fledgling writer’s not understanding punctuation.

She could enter a richer space in her studio, away from what was then a very provincial province.

W.B. Yeats, who knew about the provinces and the larger scheme of things, ended one poem with,

There’s not a fool can call me friend

And I may dine at journey’s end

With Landor and with Donne.

Carol had the company of Rembrandt, and Van Gogh, and Chagall, and Soutine, and Rouault, and Käthe Kollwitz, and Edvard Munch, and more more more.

She had her growing collection of art books. She subscribed to Art News and Art in America.

Travel to and in Europe was cheap in those days.

So we visited galleries in London, Brussels, Amsterdam, Paris.

Course of events.

We had a top-floor apartment on Queen Street, with bed bugs, opposite the Halifax Infirmary.

She threw herself into figure drawing with an ad hoc sketch group that included the generously helpful Gerry Roach.

She was sought out by the buoyant Halifax-born artist Aileen Meagher, who’d won a medal in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, taught art in the local school system, poured Jameson whisky free-hand for friends, and introduced Carol to the natural beauties of the region, including a beach with the granite rocks like large eggs that figured later in her paintings.

She did still lives, cemetery pictures (the city, if art-poor, was graves-rich), and seascapes, particularly down in the charming Macleod cottages at Green Bay, of which the drawings “Tidal Rocks” VIEW and “Wild Surf” VIEW are a couple of examples.

She was energized by Provence and the spirit of Van Gogh during two summers in our beloved hill village near Aix, Seillons-Source-d’Argens.

The resulting pictures were exhibited in the national Canadian shows of that time, and admired, and bought. That was before artists who neither painted, sculpted, drew, or printed demanded that such shows be discontinued, with the result that each Province retreated into itself and raised the art equivalent of tariff walls.

But what with Vietnam and the changing art scene, she was dissatisfied with being off in the margins.

For two or three years she rethought her art, trying experiments like “Kissing the Moon,” VIEW with its strange twisting of space and the doubling that appeared in a number of her subsequent works.

And in 1967 she made a breakthrough with the couple in “Grandparents 1,” VIEW starting on the ascent that would end in the 1977 show.

Irony

But there was an irony in all this.

Her passion for art history, her hunger for students at Dalhousie and King’s to be able to experience that rich culture, was also a curse.

Struggles

Here I must be brief, not least because hearing about others’ battles long ago can be a bore. (Was Uncle Dick really the total jerk that Aunt Maggie keeps insisting he was?)

The show in 1977 came after a failed campaign, extending across several years, and involving several committees and reports, to have an Art History Department established at Dalhousie, informed by the normal Dalhousie standards and procedures. The young visiting professor, Martin Kemp, who wrote the initial report recommending it, is now Professor of Art History at Oxford.

And there was an increasingly bitter struggle on the gallery committee, of which Carol was a member, to have the Dalhousie Art Gallery be a Dalhousie-oriented operation, rather than an adversarial outpost of postmodernism.

Such goings-on may appear to the outsider like storms in tea-cups. Gerard Manley Hopkins knew better. He spoke of how,

Honour is flashed off exploit, so we say; …

But be the war within, the brand [i.e. sword] we wield

Unseen, the heroic breast not outward-steeled,

Earth hears no hurtle then from fiercest fray.

Yeats, too, knew about hidden wounds. In “To a Friend whose Work has come to Nothing,” he asked,

… how can you compete,

Being honour-bred, with one

Who, were it proved he lies,

Were neither shamed in his own

Nor in his neighbours’ eyes?

Carol’s chief supporter on the committee, Nita Graham, was also honour-bred.

In art-political terms, Carol figured as the Adversary—the one thoroughly credentialed free-lance in this Province who spoke for the expressive humanistic European tradition.

In a review of a student show in 1971 for Dartmouth’s 4th Estate, editorially headed “Students Deserve Better Challenge than Keeping Up with Trends,” she wrote,

I have the uneasy feeling that the students are trying to start at the top without a vocabulary of natural forms or understanding of artistic development as presented by the study of art history and the lives of individual artists….

The number of timid and confused pieces in this exhibition is almost heartbreaking after all the talk about free self-expression and expanded consciousness.

Drawing—that millenia-old entry point into the art of seeing with one’s own eyes, that common denominator in the work of so many artists and linking us in our common humanity back to the extraordinary cave artists of pre-history—had been dropped from the curriculum as no longer “relevant.” VIEW

She spoke up, from time to time, on behalf of other local artists outside the ivory walls of the academy, taking risks that a number of them couldn’t afford.

She was involved in the creation of V.A.N.S., the organization of Nova Scotia artists who—oh the bourgeois shame of it!—tried to make an unsubsidized living from their art.

But she was just a Woman, wasn’t she? And over-reactive, no doubt? And maybe a bit self-promoting?

Ironical smiles and shrugs in the corridors of power aren’t minuted.

She kept excellent records, though, and her papers will go to the Provincial Archives.

Penalties

Effectively she became persona non grata with the Canadian art establishment.

The only works of hers in the Canadian National Gallery are a few pieces from the early Sixties, in terms of which she is briefly characterized in the book Canadian Women Artists (1997).

She isn’t mentioned at all in Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century (1999) by the art historian Joan Murray, who was director of the McLaughlin Gallery in Ontario when the 1977 exhibition was hung there.

I continue to find that unforgivable.

There may have been other exclusions during her lifetime that I didn’t learn about. She wasn’t a complainer.

And it still goes on. Nothing by her has been in the permanent upstairs display of Maritime artists in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and only two pieces have been, briefly, on the Gallery’s walls since 2001, and nothing has been on view in the Dalhousie gallery for at least the past three years.

No article, so far as I know (and my permission would have had to be sought for the use of illustrations), has appeared since her death.

She had the generous supportiveness of Mary Sparling at Mount Saint Vincent and the more than merely commercial enthusiasm of artist Ineke Graham at Studio 21, also the unstinting admiration of Ian Lumsden at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton.

But even so, she could never have lived off her art. Her income one year, as I recall, was about $1700.

Fortunately the unsubsidized vision and tenacity of Joyce Stevenson VIEW have given us, along with lovely images by other outsider Nova Scotia artists, those glowing Thistle Dance cards in the racks.

A knowledgeable older woman artist remarked of a mutual acquaintance that what he wanted was fame and that what Carol wanted was recognition.

With recognition, what you have to say will at least be listened to.

Ideological conflict

But actually, the local conflict here was simply part of a larger Kulturkampf being fought elsewhere.

In part, that war was a power-and-prestige struggle between the opposed paradigms of two very intelligent and Lucifer-proud artists—the intent gazing and super-abundant visual inventing of Picasso, and the ironic, games-playing, “conceptual” distancing of Marcel Duchamp.

On the ground, it involved the paradigm of real, challenging art-thinking and making, versus mere bourgeois-flattering, commercial self-expression.

Paradigm

So before turning positively to Carol’s works (you’re being very patient), I want by way of contrast to offer an image of a different kind of art activity from Picasso’s and hers.

It takes us back to the question of identity and presence that I raised at the outset.

My text, which I’d typed out and was on her studio wall, is from Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols,

Let me get rid [he says] of a prejudice here. Idealizing does not consist, as is commonly held, in subtracting or discounting the petty and inconsequential. What is decisive is rather a tremendous drive to bring out the main features so that the others disappear in the process. …

It would be possible to imagine an opposite state, a specific anti-artistry by instinct—a mode of being which would impoverish all things, making them thin and subjective.

Performance

Let me share with you an imagined event.

A man sits in an empty room in front of a stationary video camera, between two of what look like those cylindrical metal ashtrays you used to get in hotel lobbies and airport lounges.

Holding what looks like a bowling ball, one of the small ones, but is probably hollow, he leans over, puts the ball in the ashtray to his right, and raises his right arm vertically.

Picks up the ball, leans the other way puts the ball in the other cylinder, raises his left arm.

Repeat… repeat… repeat…

He does this 201 times, as shown on a row of changing numbers—red numbers.

What’s going on? His face isn’t expressive—not sullen, not angry, not hurting.

Well, this, you see, is a protest piece about War, the folly of war, the repeated exchange of missiles, the patriotic gestures, the ashes.

And why 201 times?

Well, that was the official length of the Battle of Stalingrad in World War 2, a battle, between opposed ideologies, of particular savagery and major importance.

So the performance is The Stalingrad Follies.

(These days it would probably be the Iwo Jima Follies, the two imperialist Pacific adversaries being, of course, of course, like peas in a pod. But that battle only lasted 37 days.)

Implications

A few things strike me about this, considered as an art event.

There used to be those little plastic steering wheels for kids in cars. (Maybe there still are?) Mom is turning a wheel, Junior beside her is turning a wheel, therefore he is doing the same kind of thing.

But the mother is steering the car, with movements of the wheel charged with possible serious consequences, and requiring sustained attention.

The kid is merely rotating a bit of plastic.

The points of resemblance between, on the one hand, ball and ashtrays, and on the other, the savagery at Stalingrad--the tunnel life in the rubble, the killing cold, the hand-to-hand combat, the dreaded snipers, the hunger, the sleeplessness--are like that, if taken at face value.

But of course we mustn’t do that, must we?

And in fact we seem to be into a curious variant of romanticism here, an example of Nietzsche’s paradoxical-sounding subjectivity, in which what matters is what’s going on in the mind of the artist-performer.

But what is going on here?

If what we’ve seen is the signifier, what is the signified?

A mere message to the effect that war is absurd would be vapid—instant cliché.

Are we asked to assume a focused moral seriousness while the performance is going on, like someone doing penance on his knees or meditating?

A feeling of the absurdity of war?

But what would that be like? What does he know about the details of Stalingrad? Is he thinking of that TV documentary, maybe, or that movie with Ed Harris about Russian and German snipers?

Or alternatively, is there a programmatic numbness and not feeling—a distancing from folly?

But you know, he could be thinking about his coming vacation.

The point is the simultaneous inaccessibility and privileging. We don’t know what’s there in his head, but it must be serious because this is Art. And it’s Art because he’s an Artist.

There may also be a spectral presence of the Romantic symbol, whereby something in some sense, which I admit I don’t understand, “is” what it refers to.

Interesting, anyway.

Pink Dachshund

Another of my imagined artist’s projects was the Pink Dachshund series.

He stenciled in pink the silhouette of a dachshund on a variety of surfaces—newsprint, rice-paper, parchment, velvet, T-shirts, concrete, etc.—and did free-standing cut-outs in plywood, and other ingenuities.

Which gave him a “signature.” If you happened to mention his name to someone, they’d say, oh, yes, the pink dachshund.

If someone says incredulously to a business associate, “You mean you paid three thousand bucks for a stenciled pink dachshund on black velvet,” the proud owner can reply, “Oh no, that’s not any old pink dachshund on black velvet, that’s part of the Pink Dachshund Series.”

Which shuts dummy up.

I must hasten to add (pink having been the colour of the identifying triangles worn by homosexuals in the German concentration camps) that I like pink dachsunds.

We had one ourselves.

Here he is. His name is Vincent Van Dogh.

[I produce him and hold him up, wearing his little mortar-board.]

[Laughter]

Art Education

I’m caricaturing, obviously. Well, actually not all that much with the Pink Dachshund.

(Dare I breathe a couple of words? No, no, better not.)

It isn’t really funny, though.

Carol considered it wrong to pressure young art students in such directions early on, as distinct from imparting or demanding skills that would function for them whatever paths they figured out.

Which might include fantasy and the surreal.

She liked E.M. Forster’s anecdote about the old lady who, when told that logic was a way of organizing your thoughts so that you could express them clearly, said, “But how can I know what I think till I see what I say?”

She thought it unfair to bombard students with tertiary-level jargon and half-understood concepts derived from notoriously difficult writers like Derrida.

Or encourage a chronic suspiciousness about the art of the past and an incapacity or unwillingness to enter into and experience the “felt life” out there.

Including the beauty.

Art

If you know something about these matters, you can sense the apologetics and intimidation whereby the mere act of raising such questions is bourgeois philistinism.

I’m sure the notion of self-abnegation would come into the bowling-ball show. He is selflessly repeating those actions.

But the assumption that there is automatic merit to “art” (hence the ongoing confrontational extending of its boundaries) is as foolish—and as romantic—as assuming that a novel or play is automatically good.

(John Baxter and I, as admirers of the great outsider poet-critic Yvor Winters, would have no trouble saying, “It’s in verse, and so it’s a poem, but it’s a bad poem.”)

And there’s a further displacement, away from the signifier to the artist’s presumed thought-processes when devising the project.

And a curious reversal with respect to the idea of “challenging” art.

Challenge

When Duchamp did things first with his readymades, there was indeed a weight of challenge against the whole idea of what art was. But also, the signifiers had their own interesting identities.

His snow shovel, bottle rack, and urinal, stripped of snow, bottles, and the customary liquids (the urinal is turned on its axis) had plastic form and were redefinings of sculpture. VIEW VIEW

Since then, in a drive to escape from the “aesthetic,” we’ve had, over the years, a variety of thinner and more incongruous, or more banal, or more distasteful signifiers to replicate the challenge.

Except that when such works are created inside the academy, and with institutional support, the original situation is exactly reversed.

They are not challenges to the academy, they are challenges by the academy to civilians, maybe tax-paying, maybe—horrors! —“bourgeois,” outside the academy.

You know, I can’t help thinking of this as Acadada, or academic Dada—an art of the Acadademy, the art of, who else? Professor Canadada.

And more exclusionarily elitist, when it comes to the proletariat, than the King’s Foundation Year Programme, with its readable and empowering texts, some of which, such as Plato’s Republic, members of the proletariat used to study by themselves in search of wisdom.

It’s a sad view of art, and of artistic integrity, that would seek to elevate this kind of art as the real thing and marginalize the making of “mere images” to go on walls, public or private, and light up a room or a life.

Such as those impeccably reproduced greeting-card-size images by Nova Scotian artists on the racks in stores.

It’s sad when there’s a dislike and distrust of beauty, wit, fantasy.

Trying to distinguish between art and craft, I once suggested that nowadays if it’s beautiful and useful it’s craft, if it’s useless and ugly, it’s art.

Essentializing

What, then, finally (picture-show-time), was Carol doing in contrast?

I think she was increasingly engaged, in her finished-up works, in creating thick signifiers, signifiers not in need of verbal explication because enough was given in the image itself.

She pressed forward to fullness and to the creating of epitomes, epitomizing images, large and small.

An image, as I’m using the term here, is the visual equivalent of a tune. Lots of people can do harmonies, but writing a memorable tune?

“Yesterday”? “The Maple Leaf Rag”? The choral part of Beethoven’s Ninth? Not all that easy.

A tune persists in a variety of performance—massed brass bands, a mouth organ, bagpipes, the shower stall.

The epitomizing art image likewise persists in various forms—black-and-white, postcard-size, cheap newsprint, postage-stamp-size—, Dali’s watches, Rousseau’s “The Sleeping Gypsy VIEW,” Munch’s “The Scream,” Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa,” Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring VIEW,” Rembrandt’s “The Jewish Bride,” etc., etc.

Even if you knew nothing about the artists, and these were their only works, they would still speak to you.

The icons in such works, even when having the status of repeated symbols, have their own value-bearing identities within each work.

Grünewald’s cross isn’t Rubens’ cross.

Delacroix’s poignant madly staring tiger recalling a vanished landscape in his great lithograph is that tiger, obviously sketched from life behind bars, before it becomes a symbol of lost powers, like Baudelaire’s swan. VIEW

A Chardin or Vermeer pitcher is charged with the values of its own use by and among ongoing lives.

That photo of Carol with her brushes seems to me to take us beyond the merely social, the merely personal. This is an artist pondering—an iconic artist.

An image. An epitome. VIEW

So much depends on faces in a lot of art. A face, caught in a decisive moment, or with the gravitas of self-presentation, can encapsulate a whole mode of being.

Curiously, there are few faces in Carol’s paintings. But there is a lot of body English.

I would guess that she was reaching for the general, rather than the individual specific.

For, perhaps, “character” rather than “personality.”

Images

Here, to begin with, are two important pieces by Carol from 1962 and 1963, “The Sun Setting” and “The Widow.”

“The Sun Setting VIEW” is our tiny top-floor dining-room on bed-buggy Queen Street transformed, universalized. The cityscape, no longer Halifax, is dream-like, seen across unstructured space. The support surface for the vase is like a stone slab.

The west is traditionally the land of departure, over which the sun goes down. But the flowers on the greyness are still vibrant with life, and the air is moving.

“The Widow VIEW” was elicited by the Kennedy assassination, and if she’d been canny she could probably have got commercial mileage from the image. But for her it was about widowhood and grieving, not about a political event. She’d probably have thought it tacky to profit from a public mourning.

Apparently the first thing she said after a friend gave her the news was, “Oh, that poor woman!”

(My own unregenerate first thought was, “Good. Now we can have Lyndon Johnson.”)

[Which got laughs rather than gasps. Great audience! That’s sophistication for you.]

So now let’s embark with Carol on her more methodical concentratings, essentializings, distillings.

Provence

In our two summers in Seillons-Source-d’Argens, with nothing in our area, east of Aix, corresponding to those focal points that Van Gogh found around and in Arles—drawbridges, coloured fishing boats on the beach, fields with carts, a row of stone sarcophagi, enclosed gardens—she sketched a lot, both calligraphically and realistically. VIEW VIEW

But she also, later on, did a dense, stylized ink drawing, filling the page with olive trees and cypresses. VIEW

And she produced, also back in Halifax, the extraordinary “Garden Diagram,” compressing a whole complex area in the castle in Villeneuve-les-Avignons, twisting the foreground formal garden through ninety degrees, relative to the wilder upper part. VIEW

Also, if you look at the top of that picture, which was done in 1975, you’ll see a tiny alley of cypresses.

Well, here, from a couple of years earlier, is her first go at that pathway in the rough upper area of the castle, based on a photo she’d thumb-tacked to the studio wall.

And already she’s simplifying and intensifying, heightening the cypresses, opening up the spaces between them, and removing the low northern wall of the castle, while adding quite un-Provencal clouds. VIEW VIEW

And here, finally, is “Moon Alley,” finished in 1969, and we’re well into symbolism. VIEW

I can’t tell you what is meant. I’m not good at some symbolisms. It’s the moon, it’s night, it’s magical. It’s what you might feel out there at night.

The moon mattered to her.

Back in 1962 she’d enjoyed a song by Brendan Behan, apropos of space-shots, with the line, “Don’t muck about with the moon.”

Figure

Here’s another bit of essentializing.

In the sketching group that I mentioned she did a lightning sketch of a nude figure half on a chair, probably without even looking at the paper. Then a fuller one, with colored pencils. VIEW VIEW

Then, several years later, she did this strongly modeled pencil nude, turning the side of the chair into a kind of balustrade, emphasizing the curve of the leg, lengthening the left arm, and providing an enigmatic, inward-gazing face quite unlike the actual beautiful one of Jeanie James. VIEW

At least I’ve always assumed that that was the sequence. But the numbering of the first two versions is odd. Could the lightning sketch have been a reaching ahead from the more conservative version?

Engagement

What about “engagement,” these being the socially conscious Sixties and Seventies?

Well, suppose we return now to that car painting, “Head Wound.” VIEW

She had a large image bank of clippings from newspapers, magazines, seed catalogues, etc.

(The Mexican weekly tabloid Alarma, with its murdered drug lords, assorted imprisoned “fiends” of various kinds, and serialized history of the Revolution of 1910, was among her sources, though those particular monsters didn’t get into her art.)

In among the clippings is the newspaper photo of a car that has smashed headlong into a tree. VIEW

Among her drawings is one in which the car is a meticulous copy but the tree is energized now, rather than being what could virtually be a telephone pole, and the car feels in motion, arrested just at the moment of impact, the tree’s roots gripping the ground in the form of a huge ball of earth. VIEW

And we’re away from a specific accident.

In “Head Wound” we have a complete essentializing, a superb dramatic imagining, almost science-fictional, almost afloat in the sky, with the arm outflung and the head bleeding, the individual universalized. What it can mean to crash.

Essence of body, essence of car.

(She had had to take about forty lessons from a German-Canadian disciplinarian before getting her licence in preparation for the 1969 Mexico trip. After which she was a superb driver, first in our four-wheel-drive International Scout and later in our white VW Rabbit.)

The image does the work, the signifier is rich, words are not needed. For me it is her strongest and most original painting.

Protest

She had a transformational go at war during the Vietnam Sixties.

Here she is at work on an extraordinary painting, a huge red sun with dead soldiers in the vegetation below it. Somewhere I’ve seen it in colour, but she may have painted over it. Did she consider it too journalistic? VIEW

Here it is frontally. VIEW

She also did “Camouflage” (1969), which was popular. Two soldiers in camouflage uniforms are carrying a stretcher through dense tropical foliage from which they are barely distinguishable. The news photo of such a group is in her image bank.

And then there’s the symbolic-sinister shooting amid nature, “Green Fire.” Interestingly, we have a slide of it at an earlier stage and can see the process of enrichment, the plenitude of greenery.

In the earlier stage, the curve and sky on the right are like the edge of the globe. This is the only time she did something like that. VIEW In the final version, all areas are filled in, with a half opened and winged something on the right. VIEW

In “Lamentation” she protested about injury to the environment. It is almost a poster image. VIEW

A fight of several years in the Eighties by the valiant Friends of the Public Gardens to prevent a highrise development from overshadowing the lovely Halifax Public Gardens was reduced to “Fire in the Gardens.” VIEW

In an unfinished triptych she did in Ajijic, while she was feeling her way back into oils, she packs in a variety of pollutants, together with an operating theatre in the middle. The centre panel gave her trouble, and she might have worked more on it back in Halifax. But it shows the strength of her concern. VIEW

The right panel is more resolved. VIEW

Series

My final example in this part is a major series, obviously rooted deep in her psyche, that included the “Couple 2” painting and “Grandparents 1.”

Series are varied.

Goya’s great Disasters of War was a series, a succession of individual stills as it were, documenting the horrors of the campaign by and against Napoleon’s troops in Spain. VIEW

Picasso did endless-seeming heads of his women, making all manner of variations, and expressing a variety of moods, including hatred and childish resentment. (Why did Dora have to CRY when he abused and humiliated her verbally?)

Monet painted haystacks in changing lights.

Nova Scotia’s Geoff Butler did a lovely witty angel series, imagining situation after situation, largely playful, in which an angel figures. VIEW

Some series, on the other hand, can be a bit like the post-Disney cartooning in which only one or two elements move in each frame—an arm, an eyebrow.

Less inventing is required, and the distance between possible peaks and lows diminished.

And they establish a “signature.”

Such as the Pink Dachshund series.

Including the celebrated “On a Roll: 8.25–2.57,” in which row after row of small pink dachshunds were stenciled on a long roll of canvas during a given time frame, chosen aleatorily, I forget how.

Couples

And Carol’s couples?

She cared a lot about couples. Rembrandt’s “The Jewish Bride” was the high point of two or three of our visits to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. VIEW

Well, here are hers.

The first two items, from the Fifties, seem to express a hope—a monotype couple still together in old age; an etched odd couple together—fat lady, skinny gent. VIEW VIEW

The next four derive in part from Lawrence’s The Rainbow—the ideal, poised, sexual separateness yet connectedness of equals in “Grandparents 1” and “Grandparents 2” VIEW VIEW; the more troubled and aggressive yet still poised couple of the next generation VIEW; the lacerating warring after that. VIEW

As I said, I think of “Couple 2” as her “Guernica” of the sex war.

With “The Equilibrists” much has gone at the center, but there is still a tenderness on the woman’s part. VIEW

More stylized couples appear in “The Golden Chain” and two cartoonish nude figures facing each other on a branch. VIEW VIEW

In Sarah Orne Jewitt’s The Country of the Pointed Firs, which she owned, there’s the phrase “the golden chain of love and remembrance.”

Survival

So, now, how about her survival after what I’ve called the break?

She once said during what, for want of a better word, I’ll call our courtship that she had no personality but lots of character. Which, if one means by personality the kind that imposes itself, the stylized public art self, the artsy costume, etc., was true.

A personality wouldn’t have brought me a cup of tea in bed each morning.

I think we can speak now in this new phase, in terms of character in a full sense.

If personality is temperament on display, character is a cumulative series of purposeful acts and abstentions.

Public

She acted in the world. She spoke up. She fought, though not temperamentally aggressive.

She was an efficient, good-humored acting director of the Dalhousie Art Gallery while a new permanency was being sought. (No, she had NOT aspired to that post for herself.)

She inaugurated talks and film shows for the public.

Picked Nova Scotia artists for the annual drawing show, the first time this had been done—and the first time Ottawa refused funding, on the grounds of quality. She found it anyway.

Charmed other art administrators at conferences, who were surprised by how different she was from her grapevine reputation for being difficult.

As was, he told her at the end of her year’s service, the president of Dalhousie.

(She observed wryly that she had the respect as an administrator that she was denied as a mere artist. )

The year after the 1977 show, she curated at Mount Saint Vincent University, a marvelous show of Expressionist prints from the National Gallery of Canada, extending the term to artists like Rembrandt, Goya, and Delacroix. She wrote the catalogue essay, and gave a set of lectures. She hoped the show would be visited by students.

It—or rather, the accompanying texts, for he ignored the works themselves— was attacked in print by a second-level art administrator for whom Expressionism was a soft option for bourgeois gallery goers, and insufficiently civilizing, in contrast to art like Matisse’s.

In an unsent reply, she said, “When --------- has nursed as many dying people as I have, he can prate of humane values. Till then, let him shut up.” She was presumably referring to her time as a nurse’s aide in the cancer recovery ward.

Later she gave a slide lecture on “The Search for Paradise: Garden Painting in Western Art.”

Reviewing

She was an excellent reviewer in the 1980s for Joe Sherman’s Arts Atlantic, and grateful to Joe for his supportiveness.

Reviewing in 1984 the Seventh Annual Dalhousie Drawing Show, in which the term “drawing” had been stretched so as to include an actual ladder and pail, she dealt deftly with pretentious nonsense.

Suppose that I go into a restaurant and order a piece of chocolate cake and the waitress brings me a piece of apple pie with a fancy explanation of how apple pie really is chocolate cake and the manager just happens to know a pastry cook who makes the best apple pie in town and how I must eat apple pie as if it were really chocolate cake? Even if this is the best apple pie in the whole of North America, assuming I had my heart set on a piece of chocolate cake, I’m not going to be very favourably disposed toward that pie. I would probably dislike it—as well as the waitress, the pastry cook, the manager and the restaurant….

And this brings me finally to the Seventh Dalhousie Drawing Exhibition, which consists of sixteen works of which at least eleven are apple pie. [see Writings>Actual Size]

In the same review, picking up on the guest curator’s reference to “cultural frontiers,” she reminded readers of “the fact that, over the past four years, Dalhousie Art Gallery has not exhibited (apart from one or two pieces from the permanent collection and the current Colville show) a single work by a contemporary Maritime artist who is not connected directly with NSCAD [Nova Scotia College of Art and Design].”

My own contention [she said] is that one of those “significant frontiers” has been established in Halifax by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and Dalhousie Art Gallery. It is called Barrington Street, and it separates the academy from the organic creativity of a community and a region.

She was severe the year before about a show of young feminists at Mount Saint Vincent, concluding with,

Coming away from the gallery was like leaving a committee meeting on the evils of the media as seen by the contemporary art establishment, and I felt bored, exasperated, and saddened. Seven young women, supposedly in the prime of their creativity, all liberated from oppressive sexism, I presume, and all floating on grants and awards from this or that source (eleven Canada Council, eight others) could have better things to say and better ways of saying them. [see Writings>Appearing]

But she turned to and talked perceptively about the individual pieces of pie once you stopped thinking of things like gouged plywood and a standing metal wolf in silhouette as drawings.

And she coped empathetically with art very different from hers, such as Tim Zuck’s, remarking that his having emerged from the “obstacle course [of his art education] holding the paint brush by the handle and not the bristles is performance art on a grand scale.” [see Writings>Tim Zuck]

She was generous to several younger women artists.

And had a deep respect for older Nova Scotian artists like Ruth Wainwright and Aileen Meagher, both of whom had taken classes in Provincetown from the distinguished artist-teacher Hans Hoffman.

She had her own admirers, too.

Ian Wiseman, who taught at King’s, loved her work, and wrote a couple of appreciative articles about it.

Janet Smith, with a cameraman and sound person, did a half-hour documentary interview with her.

In 1987, Ian Lumsden, whose persistence finally secured the funding, curated for the Beaverbrook a retrospective show of eighty-eight of her drawings, and gave her plenty of input.

I’m sure the show was her statement about the variety possible when you ask for chocolate cake and are given it.

Other Carol

But how about the interior, the other Carol?

She was not a feminist, and disliked the label “woman artist.”

She got along well with both women and men, inside and outside the arts community, at least if they had a sense of humour, weren’t “officious” (her term), and were concerned with more than their own advancement.

But there was a lot of pain and anger inside at times.

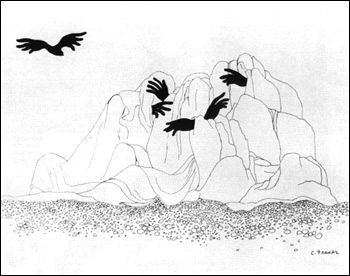

What I find remarkable is how she transmuted it, starting back in the early Seventies with the multi-armed female figure in “Ambivalence,” the monstrous dominative male apparition, and the cowering shrouded figures terrified by the free-flying bird in “The Geology of Fear.” VIEW VIEW VIEW

The nude in “Migraine,” limp on a couch (she had migraines herself), is essence of pain, contrasting ironically with Goya’s “Nude Maya” and Manet’s “Olympia.” VIEW VIEW VIEW

And the woman swallowing a bitter pill becomes an avenging Fury when you turn her on her side. VIEW VIEW

Narrowing down

More generally, she turned away from the ambitions of 1977 to smaller and more symbolic works.

The symbolism was not always self-explanatory, nor meant to be. Having had her apple pie and chocolate cake turned down and her vegetation dissed, she was giving them stones.

They were not self-pitying stones, but not noticeably happy ones—balanced precariously on fences in “Risky Conditions at Sandy Cove,” shut out from one another by window panes, falling apart and held together by cords, attacked by butterflies. VIEW VIEW

And in 1979 she did the bravura drawing “Six Women,” showing six highly stylized naked women on a stony beach. ( Les Demoiselles de Nouvelle-Ecosse? ) That and “Squash Blossoms” seem to me her two most brilliant drawings. VIEW

There was also a couple of small, stylized triptychs with male and female symbols. VIEW

She had in her head, I’m sure, the lines by Wallace Stevens beginning “The Rock cannot be broken. It is the truth.” [See Intellectual>Wallace Stevens>xxi]

Comforters

Stevens and his celebration of the power of imagination, taking us beyond the “nothing that is not there and nothing that is,” was a great comfort to her, I know.

And she hated all the more the thought of modes of art-teaching that stunted the imagination because not providing, or actively discouraging, the three-dimensional reaching out to other beings, animate or inanimate, that in turn can take one seriously beyond realism.

She drew comfort too from the oddly unpigeonholeable career of Oskar Kokoschka, VIEW who despite terrible psychic wounds during and after WW1 (at one point he had a large sex doll) kept going with warm portraits and landscapes. She said of him in a memorial lecture,

His life speaks of continuous affirmation. In his painting and graphic art, his plays, poems, essays and books, and also through teaching and in his example of self-generating ability to find and follow his own way regardless of worldly comment, he is a paradigm of integrity unique in 20th-century art. ((“Kokoschka: Knight Errant of 20th Century Painting”)

And I’m sure she had, among her mental anthology of poetic lines, T.S.Eliot’s

And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling

Undisciplined squads of emotion.

She also—don’t laugh—loved Arthur W. Upfield’s novels about Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonapart (“Call me Bony,” he told people who earned his trust), abandoned as a half-white aboriginal baby, and named by the missionaries who brought him up.

Bony tackled a large variety of cases in a variety of Australian locales (the best book is The Bushman Who Came Back), and knew always that if he were ever to give up and fail to solve a case, it would be back to the bush for him, his sustaining pride gone.

Philosophical

Most importantly, she knew philosophically and aesthetically that, Romantic theory to the contrary, we are not all of a piece organically, and that when you do weaker work at times, it doesn’t mean that all the virtue has drained from you forever.

She didn’t, though no optimist, have a fatalistic sense of doom.

I am sure, though we never talked about it, that she saw things much more in terms of the pilgrimage, never over till it’s over, of The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Each case, like Bony’s, was a new case.

(Including gardening, and tending a sick cat, and hosting a dinner party.)

She could be playful and witty, as with her glove bird. VIEW

And wryly humorous about herself.

Among her papers was a strip from B.C.

In the first panel, one of the bearded characters is saying, “I want to be one with the universe. I want to be a note in the great rhythmic beat of life.”

In the second— ZOT— he is knocked upside down by a bolt of lightning.

In the third, worse for wear, he says, “It’s a terrible thing to be rejected by the cosmos.”

What mattered was doing your best by the work in front of you, the task you’ve committed to, and keeping going, refusing to let the bastards grind you down.

She followed Joyce Cary’s Gully Jimson, in a novel she admired, in avoiding, as much as possible, a competitive hatred and envy, though she well understood Gerard Manley Hopkins’ query. “Why do sinners’ ways prosper, and why must / Disappointment all I endeavour end?”

But there was also, in the Seventies and Eighties, a lot of chronic ill-health, low energy, and depression, what with asthma (she almost died of an attack in 1982) and paint-and-food allergies.

Practical nourishers

Her two principal re-energizers were Mexico, during my sabbaticals of 1981–82 and 1989–90, and her watercolour shows at Studio 21, in which the time between creation and display was agreeably short.

Mexico

Mexico was so liberating because it was totally NOT Halifax, Nova Scotia.

It was a place of more primary emotions and primary experiences, with the suffering, and endurance, and violence of a difficult history, and a rich daily feeding of the eye and mind, and seasonal rituals, Christian and pagan, and a sense still of the presence of the pre-Colombian past.

Our own Tepoztlán—near Cuernavaca, and with its Wikipedia page now— had an Inca temple up on the crags above it.

A dangerous country, with scary police, and risky driving (we were almost totaled in 1990), and a legal system in which if you had an accident you were presumed guilty until found innocent.

And gorgeous towns like Pátzcuaro and Zacatécas.

Mexico was much richer than Provence, which for her was more an affair of the mind—Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Bonnard had worked in different parts of it—the present-day art-actuality being thin.

“Nature” was more intense, the tropical forms wilder and faster growing, the lives of animals more intermingled with those of humans, their treatment less sentimental, the adobe of the poorer dwellings more organic.

And in Mexico she wasn’t defined as the Oakland Road cat woman, the daily self, the gallery-committee dragon lady.

And there were interesting people there, particularly our French friend Claude Besneault, well-born, awarded the Croix de Guerre for activities as a schoolgirl during the Occupation, wife for a while of a movie cameraman, frequenter with Truffaut, Godard, and others of the Cinémathèque (“Tait toi et soit belle,” she was told—“Shut up and be beautiful.”), mistress to Buñuel at one stage, and with a sense of humor.

She laughed instantly when told that the paw which our timid older cat Shinski would extend to you when you said “Paw-paw” was the Mitt of Sissy Puss.

With Claude, Carol was breathing a freer air.

Surrealism

Had she known Frida Kahlo’s work when she did her breakthrough painting “The Grandparents” in 1968–69 before we went to Mexico?

I simply don’t know.

Mexico was not on her mental map before we set out (“Are you out of your mind?” she said when I told her in the summer of ’68 that we should drive there for my sabbatical), and Kahlo was not at that time the North American name that she would become.

A single reproduction in an art ‘zine could have been a stimulus, of course.

Or, thinking about the apartness in Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” and the first-generation connectedness in Lawrence’s The Rainbow, she could have created her own synthesis. VIEW

I know she’d seen a painting by the surrealistic Pavel Tchelichew (1898–1957) with connective tubes and tendrils in it, as Kahlo may have done.

Was she herself, like Kahlo, an artist who could have been claimed for Surrealism, at least in some of her oeuvre, without in any way belonging to a “school”?

Her works, with some obvious exceptions, are less fantastical than what I have examined, in reproduction, by artists like Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, and Remedios Varos.

If Expressionism was an intensification of Realism in one direction, Carol’s kind of surrealism, with its ongoing consciousness of the experiential body, and of landscapes, was an intensification of it in another.

In any event, she was our own Kahlo, here in Nova Scotia.

And an inspiration to younger artists figuring out their own paths and refusing to be intimidated by the celebration, in the name of realism, of “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

Like Orwell, she had no time for the “smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.”

For which she herself was dropped down the Memory Hole in that history of 20th century Canadian art that I mentioned earlier.

A calendar of Kahlo’s self-portraits was on her sunroom wall when she died.

Sabbaticals, 1969–70, 1981–82: Tepoztlán

Several major paintings in the 1977 show had been done during our first sabbatical stay in Tepoztlán, 1969–70, including “Head Wound.”

During our second stay there, 1981-82, she first essentialized aspects of Mexico in oils and then, when they became so tightly worked that making changes was difficult, liberated herself by dripping colored inks onto a sheet of glass, laying a sheet of paper on it, and, with a brush, developing the resultant colour areas into a picture, allowing images to flow and evolve, one leading into another or suggesting new possibilities.

In “Network,” we have a, to me, enigmatic but visually lovely intimation of relationships between the organic and the technological. VIEW

“Third World Night” juxtaposes flowers and guns, the flowers lovely, the stylized guns underlying them. VIEW

“La Noche Buena,” literally “The Good Night,” is Christmas Eve in Mexico. Poinsettias are Christmas flowers. I cannot interpret the ominous symbolism of what is one of her most surrealist works. VIEW

“Playground of Escape” was, I think, the first of a set of playground paintings that she told me she hoped to do, but didn’t accomplish. VIEW

The watercolours that she did every year from then on were themselves a kind of serious playground for her.

She could now develop imagery rapidly, interweave symbols, rejoice in colour, and achieve new resonances.

Images like “Night Garden with Full Moon” were simultaneously “southern” and her own beloved garden in apotheosis. VIEW

In ones like “Departure of Summer,” she found a transformational poetry in South End residential Halifax to complement the cemeteries and lower-income cityscapes of her Sixties drawings. VIEW

The winter of “Northern Night,” done early on and maybe drawing on memories of Minnesota, was vitalizing, not a mere grey post-holiday-season absence, perilous under foot and lasting much too long. VIEW

She drew, too.

The cover image for the catalogue of the 1987 drawing retrospective combines task-oriented and risk-taking art in “The Great Tree in the Tepoztlán Cemetery.” VIEW

A lot of patient labour went into the intricate interweaving of branches, as if the tree were caught in the actual process of growth.

And then (for we have a photo of the tree without them) she added the dog and the cat.

And compounded the risk by having the dog’s head and tongue outlined against empty sky.

Think of the Zen-like concentration required for doing that and shutting out the possibility that the slightest error could wreck the whole picture the way a wrong note at a crucial stage can wreck a piano recording.

Inside the catalogue, the drawing is paired with a pastoral one in which a dog and cat sit on elaborate metal garden chairs at a table with tea things on it, on a patch of lawn enclosed by an abundance of tropical vegetation. VIEW

The two works were intensifications of givens. There was indeed a big tree in the Tepoztlán cemetery, though of course not as complex as hers.

And the lawn furniture in the compound in which we lived that year was like that, and the vegetation behind it was almost as luxuriant. The owner was from down south, in Oaxaca, and had created a “southern”-feeling garden.

Sabbatical 1989–90: Ajijic (pronounced Ah-hee-heek)

But Carol still thought of oils as the really serious medium, and during our third stay, in Ajijic on Lake Chapala, she was working her way back into the game, thanks to a new solvent that she’d found and started trying out a couple of years earlier.

In a remarkable burst of creativity despite various distractions and interruptions—ill health, an abnormally cold wet winter (her studio area was unheated), three sets of visitors, a painful fall, a long drive up into Texas to renew our tourist visas—she did fifteen oils of various sizes, a number of them ones that she probably intended to enrich back home, and worked on fifteen watercolours, some of them simply the foundations for images.

Finale

After our drive back to Halifax in 1990 in our Rabbit, she was offered a show by Joan Martin at Nancy Poole Gallery in Toronto, into which she’d ventured when I gave a set of lectures at the University. I can well imagine her, re-energized, reworking and going on from the images she’d brought back with her.

But by then the lung cancer that claimed her in the spring of 1991, with mercifully little pain, was too busy in her body.

The face in the self-portrait at the window is miserable. It answered to inner truths, I’m sure. There would have been flowers below the window, maybe black-eyed susans. She is shut out in the inclement bleakness. VIEW The figure in the companion portrait, man of the book, doesn’t look to me like a comforter. VIEW

But the face in the first version she showed me had been glum rather than sad and hadn’t looked like her. She was annoyed when I said so, and even more annoyed when I said the same of her second attempt. I guess some of that comes across too.

In the poignant and unfinished oil “The Wall,” she achieved some of the luminosity of the watercolours. The title of that, like all the other titles of the Ajijic works, was provided posthumously. VIEW

For me the three wholly realized triumphs of that time are:

The oil “Who Are Those People and How Did They Get There?” an Edenic tribute to Rousseau (douanier, not philosophe) and a lost happiness. VIEW

The drawing “Final Soliloquy,” which she patiently filled in during the evenings in the only room with a fire, placing the culminatory rooster where the slightest error would have ruined the whole picture—a bit of REAL risk taking. VIEW

And the watercolour “All the Trumpets Sounded,” where the gates derive from the gates of the Ajijic cemetery in which for some festival the graves and tombs were embellished with paper flowers, as seen in a photo that she took. VIEW VIEW

Art is what remains when words dry up and blow away. But let’s have just a few more, not hers, but ones of which she might have approved.

John Baxter? Can you read us the relevant passage from The Pilgrim’s Progress?

[He proceeds to do so.]

Then said he, “I am going to my Father’s; and though with great difficulty I am got hither, yet now I do not repent me of all the trouble I have been at to arrive where I am. My sword I give to him who shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought His battles who now will be my rewarder.

When the day that he must go hence was come, many accompanied him to the river side, into which, as he went, he said, “Death, where is thy sting?” And as he went down deeper, he said, “Grave, where is thy victory?” So he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.

For a lot more by and about the artist, see http://www.jottings.ca/carol/site.html and www.thistledance.com

© John Fraser, August 2008