Found Pages: The Remarkable Harold Ernest (“Darcy Glinto”) Kelly, 1899–1969.

Mushroom Jungle books II: a sampling ENLARGED

The late 1940s were a period of pervasive corruption in Britain. Profit-taking from the supply of illicit drugs began to escalate during a crime wave reflecting the strict government controls imposed upon free markets. Peacetime rationing of food, clothes, petrol and raw materials, together with controls over the import and export of currency and commodities, persisted until the early 1950s. These “austerity measures,” as they were known, increased lawlessness at all levels of society, rather in the manner of the US alcohol prohibition in the 1920s.

Richard Davenport-Hynes, The Pursuit of Oblivion; A Global History of Narcotics (2002), p. 372

Here are my descriptions of the Jungle books that I have been able to get hold of.

I’ve not treated James Hadley Chase as a Jungle writer, major though the impact of his pre-1943 books was, and I’ve been selective with Darcy Glinto. For more about both of them, see Violence Inc and Sidebars 1, 2, and 3.

SH signifies annotations by Steve Holland after the first version of the page went on-line.

To access descriptions, click below or scroll down the page. The list is alphabetical. The descriptions themselves are arranged by year.

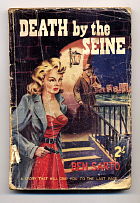

A Curtain of Glass • A Guy Named Judas • A Killer is Loose • Accused • Black Terror • Blue Blood Flows East • Broads Don’t Scare Easy • Bullets for Snoopers • Carney’s Burlesque • Chicago Dames • Coffin for a Cutie • Confessions of a Chinatown Moll • Crazy to Kill (Trouble with a Woman) • Cry Wolf Sister • Cuban Heel • Curtains for Carrie • Curves Cause Trouble • Dame in My Bed • Dared by a Dame • Death by the Seine • Death for a Doll • Deep South Slave • Don’t Touch Me • Drop Dead • Eastern Men—Chicago Women • Fireball • Foolish Cargo • Gardenia • Get Me Headquarters • Goodbye, Honey • Hear the Stripper Scream • Hell Hath No Fury • Hot Dames on Cold Slabs • I’ll Get You for This • Kill and Desire • Killer • Kitty Takes the Rap • Kiss of the Damned • Lady, Mind That Corpse • Lady—Don’t Turn Over • Ladies Sleep Alone • Landscape with Corpses • Lead Her Gently to the Grave • Love Me Hurt Me • Make Mine a Harlot • Make Mine a Shroud • Miss Otis Comes to Piccadilly • Miss Otis Goes Up • Mister Violence • My Cutie’s a Corpse • My Gun Her Body (Danger for Dinah) • My Life is My Own • Night Haunts of Paris • Nobody Died for Johnnie • No Come Back from Connie • No Dame Wants to Die • No Mortgage on a Coffin • No Orchids for Miss Blandish • No Prude • No Regrets for Clara • Not a Dog’s Chance • Now Try the Morgue • Over My Dead Body • Pay-off for Paula • Persian Pride • Pick-up Girl • Pursuit • Remember Mimi • Road Floozie • Scarred Faces • Sex • She Died Downtown • She Who Hesitates • Side-Show Girl • Sin is a Redhead • Sinful Sisters • Smuggled Sin • Snatched Dames • Some Get It • Some Look Better Dead • Stiffs Don’t Squeal • Strip-Tease Angel • Sunny • Take It and Like It • The Big Snatch • The Brute • The Dame Plays Rough • The Dead Sleep for Keeps • The Dead Stay Dumb • The Foolish Virgin Says No • The Hangman is a Woman • The Hideout • The Shayne Dame • The Snatch • The Unsuspected • This Way for Hell • Three Bad Girls • Three Steps to Hell • Tomorrow—the Chair • Too Late for Death • Too Tough to Die • Torment for Trixie • Tough On The Wops • Trixie • Trouble with a Woman • Unlucky Virgin • When Dames Get Tough • When Shall I Sleep Again • White Slave Racket • White Slaves of New Orleans • Women Hate Till Death • You’ll Never Get Me

Cecil Bishop, Black Terror (1945) NEW

A transitional work. Wartime production quality—small print, narrow margins, two staples, impossible to open pages flat. The action seems to be going on in the Thirties, maybe around 1937. Reads as though it could have been in an issue of the tuppeny large-page weekly The Thriller, unless too long at around 60,000 words. An unsexy economy cover.

Basically, as in earlier novels like John G. Brandon’s Gang War (1929), John Hunter’s When the Gunmen Came to London (1930), and Edgar Wallace’s When the Gangs Came to London (1932), the British professional class—Scotland Yard, a couple of journalists, an inspector back from the Far East—is coping with the homicidal activities of American criminals in Britain. But social order is less secure.

As we learn from the opening conversation between the Director of the United States Bureau of Investigation and Paul Hariman of the Hong-Kong police, a couple of Britons have gone missing down in redneck Hayley County, the fiefdom of rich wicked Morgan Shuyler and his son Maurice. It’s agreed that Hariman can go down and mosey around, with special attention to one of the infamous prison camps.

Cut to a work detail and abusive guards.

Every coarse and brutal word made the poor devils strive more desperately, even when they were almost collapsing with the merciless heat. They well knew what tortures awaited them at the prison camp if the guards reported unfavourably upon them to Drood, the prison warden. Men had been flogged with blacksnake whips until they were in ribbons, strung up in the dreaded sweat box until they went insane, even branded with white-hot irons at the dictates of the inhuman Drood. Their horrible screams came to the shivering prisoners in theit foul huts, but Narrow Ridge was a lonely spot, and there were none outside the camp to hear them. (10)

Hariman shoots Drood just when he is about to murder jewel-thief convict Frank Johnson out in the privacy of the swamps, and deposits Johnson with the Bureau of Investigation in Washington. The Shuylers, whose agent Drood was, flee to Britain, where the libel laws, according to Hariman, are known as the “Rogues’ Charter” because of the crimp they put on newspaper exposés.

But more than ordinary criminality is involved. As Gustav Holm, the financier father of reporter Pat Kelly’s girlfriend Irene, tells Kelly,

“The trouble about undemocratic parties is that they are treated as a joke for too long. … Today everyone is ridiculing the idea of a Fascist government for Britain or America. Five years ago they said the same thing in Germany. These movements have a habit of growing by stealth, my boy. …

They thrive on murder and terrorism. Even now, in America, the vilest men run whole districts, using every means of coercion against those who oppose them. You don’t hear much of them in England, apart of course from Huey Long’s late dictatorship in Louisiana. But they’re there all the same. …

At the present time they have branches in every state of the Union and even in Great Britain. Backed by the influence—unofficial, of course—of a certain foreign power, the [Black] Riders, now known as the Black Legion, as you have probably read, aim at securing control of the United States Government.” (58, 61)

And are now poised to spring.

But though on paper there’s a fair amount of action, the activities of the Legion mostly come to us second-hand in reports, there are no shocking violences, you don’t hear American-sounding voices, and the emphasis is more on trying to figure out what’s going on and who the mystery British head of the Legion is, with reporter Kelly (who’s not afraid to shoot a baddy in the guts) getting into and out of trouble and trying to protect Irene. The explanation at the end of what’s been going on behind the scenes has the complexity of whodunits.

Still, we have a two-page meeting of members of the Legion at which the mysterious Leader (who has an accent from the American South ) declares, “Brethren, to-night you will draw for the everlasting honour of deciding who shall strike the crushing blows we plan to aim at the effete leaders of British democracy.” (100)

And Press lord Viscount Isaacstein, owner of Kelly’s paper, is unequivocally a good guy, despite being referred to at a couple of points as “the Hebrew” and “the Jew.” No irony seems intended when we’re told that “His nose was large, not essentially Semitic, but his keen, piercing eyes were the eyes of a race that has for ever suspected—and with excellent cause—the designs of all men save their own brethren.”(74)

He’s given the last word, too, when he announces fervently to the assembled cast,

“I thank you all. You have each helped to smash an evil body—one which sought to make this country a hell for my people, and for all of you. They have learned once and for all that the strong and just Governments of England and America can and will fight them with their own vile weapons. Again I thank God that we have men and women with the courage to face these monsters and strike them down.” (127)

So, when was the book written? Its liberal tilt isn’t what one would have instantly expected from an author described on the title page as “Late of the C.I.D., New Scotland Yard.” It would be nice to feel that Bishop wrote with foresight rather than with the rectitude of hindsight.

In any event, politics would vanish from the ensuing Jungle books, as would, to judge from what I’ve read so far, the paradigm of the invasion by unruly Americans of an orderly Britain. From now on, “American” values in action in imagined American locales would be foregrounded, with plots less wide-angle and violences intensified.

In “Some Orchids for James Hadley Chase,” I express some reservations about George Orwell’s classic “Raffles and Miss Blandish,” in which he protests against the Americanisation that had achieved industrial strength with the novels of James Hadley Chase and, by implication, Darcy Glinto (He initially confused Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief with Lady—Don’t Turn Over) in 1939–42.

What he did in that essay would pervade Hoggart’s very influential characterization of the Mushroom Jungle in his partly autobiographical study of working-class culture in The Uses of Literacy (1957).

James Hadley Chase, I’ll Get You for This (1946; pb 1951)

I’d inferred from the title that this would be an injection into the Jungle of the old Chase toughness, a hope reinforced by the claim on the front cover of the Avon paperback (“complete and unabridged”) that “Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler combined might have written this gun-blazing story.” Oh yes?

Gambler and dead-shot Chester Cain (“They said I was the fastest gun-thrower in the country”) has come to Paradise Palms for a vacation, where, as courtesy to a visiting Somebody, he’s fitted up with a great hotel suite and the company of Miss Wonderly, who casually removes her two-piece when they swim out to a raft, and lets him tell her about himself, after which, back in his suite, he’s put to sleep with drugged brandy and wakes to find they’d keeping company with a corpse.

The rest of the narrative is Cain getting away from the Law and trying to clear their names, hither and yonning, There’s some “action.” He tussles with a snotty dame in her apartment, dodges cops’ bullets and projects a few of his own during a getaway, and breaks Miss Wonderley out of jail with the aid of a coffin, after fighting off a couple of crazy women behind bars. But he doesn’t feel especially tough, and while there’s a conflict between a couple of Italiano gang bosses, there isn’t a strong hoodlum presence. He isn’t even beaten up. The book would probably read OK if a name like Al Karta or Spike Morelli were on the cover. But there are no flickers of the Chase of the unexpurgated No Orchids and The Dead Stay Dumb. Chase probably never recovered from the 1942 prosecution of Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief at the Old Bailey, with the heavy fines and the voiced disgust of the prosecution, for whom it was “pornography of the vilest type, … a new type of obscenity …” whose “appeal was to sadism.” [See Sidebar 8.] LINK

Eight years later, Stephen Frances, starting out along the Chase/Glinto road in 1946, would escape by the skin of his teeth from the prosecution of several of his own novels.

Ben Sarto (Frank Dubrez Fawcett), Chicago Dames (1946)

Loathsome Big Peto operates Chicago protection racket hooking rich dames and guys (but we see only dames) on a white injectable, making them pay through the nose, and threatening them with mutilation and/or death if they don’t keep paying. Little Jewish Anna is strangled in front of virtuous Bunty Dickson, who’s intimidated enough to be willing to let Peto have her, with handsome husband Jerry no help. Bang-bang stuff (guns, I mean). Deaths. Statements like, “Anna Toplinski had fallen on her knees in ghastly terror … Bunty Dickson stood by the door. Tall and erect, her drooping eyelids showing scorn, her proud lips pursed.”

Ben Sarto, Miss Otis Comes to Piccadilly (1946)

Here is the high (or low) spot of violence in this soporifically badly written introduction of blonde American gang-leader Miss Otis to well-mannered England.

(e) Sir Surtees hung limp then, like a rag doll pressed nearly in half by the clutching arm. But Kensett didn’t let up. He went on pounding like he had pounded the policeman at the Ritzbilt on the night of the Sousa rock lifting. Once more his eyes were glowing, his nostrils opening wide and shutting like valves. The killer urge was on him again.

Miss Otis watched him, while queer little shivers of pleasure trickled up and down her spine. At last she could stand it no longer. She stooped for and grabbed the poker from the fire-grate and started in to lash the unresisting body and legs wherever she could reach them. Horrible thuds and cracks sounded as she did it. The whole scene might have come out of a devil’s dream. Two human beasts of prey smashing and crushing with the sheer voluptuousness of destruction.

Of course the little guy was dead long before they had finished. He might have been no more than the bolster the Otis had used that other day.

At last Kensett let go and the rag doll dropped to the floor.

Kensett’s face was spattered with blood. His hands were the same.

As the body fell, he and the Otis were left facing each other.

Tiger eyes, flooded with awesome light, stared into wolf eyes, glaring and bloodshot.

She made a moaning sound and tottered into his arms.

He held her tight and crushed his bloodstained mouth over hers.

They swayed together like exhausted wrestlers in a prize-fight.

Miss Otis Comes to Piccadilly, 1946, chapter VIIIn 1954, Fawcett’s Hole in Heaven was published over his own name by Sidgwick and Jackson as “the first of a series of Science Fiction novels by British writers,” edited by, of all people, the respected fictionist Angus WIlson, who should have known better and praises it fulsomely. The plot involves some kind of extra-terrestrial take-over of the body of a burn victim. The prose is tidier, the action plodding, the ideas thin, the characters dull, the book awful. Preston Yorke’s Space-Time Task Force looks like an Asimov beside it.

Hank Janson, When Dames Get Tough (1946)

The opening pages anticipate (and influenced?) those of Spillane’s Kiss Me Deadly (1952). Hank, driving at night, comes across a girl who’s screaming as three hoods do things to her, and who, when he rescues her, has nothing on under her coat and is difficult. After that he’s trying to stay ahead of the bad guys who’ve tortured Lola and are now after them both, for reasons that aren’t explained until near the end—a bit of commercial theft with Lola’s roommate Hettie in on it. There’s some heavy breathing by Hank about Lola’s perfume and a bit of stripping down to flimsy undies, also a cat-fight, watched by a bound and helpless Hank:

Then they were turning over and over in a wild flurry of silk underclothes and gleaming white thighs. Hettie got her legs wound around Lola’s neck in the scissors grip and began to apply a strangling pressure. But Lola’s long fingernails raked Httie’s thighs until the skin came off in long slivers and blood spurted from the furrows. That made Hettie release Lola’s neck pretty snappy, but although she was moaning in agony, she grappled again. I began to grow pretty sick. Every now and again there’d be a squeal of pain from one of them, a gasp, or a ripping sound as clothing tore. It was worse than any scrap I’d seen between men. (47)

Hank at this stage is a traveling salesman in beauty products.

Hank Janson, “Scarred Faces” (Scarred Faces, 1946)

After witnessing in a hotel lobby a well-dressed dame being so appalling injured by vitriol from a booby-trapped package that, after ripping off all her acid-soaked clothes, she dashes blindly out into the street, where she dies in the traffic, Hank is picked up by hoods who think he’s seen more than he should have and, after being questioned, is taken for a ride. He gets away, and investigates what turns out to be a blackmail operation bringing sexy dames together with rich and powerful men. Which he puts an end to.

Frances’ “American” prose here seems to me the best that was being written at this stage in the “Jungle.” He was chameleonic, and had obviously steeped himself, like Chase when he wrote No Orchids, in the America of the best tough fiction, including, Latimer’s, Chandler’s, probably other Black Mask writers, and Chase’s and Glinto’s several books from before their 1942 prosecution.

The rides on which Hank is taken come pretty directly out of the episode in Latimer’s The Lady in the Morgue when Bill Crane is picked up by Frankie French’s goons.

Hank Janson, “Kitty Takes the Rap” (Scarred Faces, 1946)

Frances is bursting out of the box. Things have come a long way, about the permissible, during the four years since René Raymond and Harold Kelly and their publishers were heavily fined at the Old Bailey.

After an opening ogling of her recalling that of Jonathan Latimer’s Solomon’s Vineyard (1941), Hank and beautiful classy blonde Kitty, whom he’s tried to help get away from some hoods closing in on her in the street, are taken to the gang’s hideout in the country. Hank, still a traveling salesman, is beaten up (“my face became a swollen bag of agony. The blows smacked home irresistibly, mercilessly, knuckles pounding again and again into an area of throbbing, screaming flesh”), and we’re treated to seven pages of flagellation that fill the gap left in Glinto’s No Mortgage on a Coffin (1941) when the shudder-pulp flogging of lovely Hester in an American-Nazi torture chamber is aborted after only three strokes.

Kitty, suspended by her thumbs, is flogged with what sounds like a sjambok, with time-outs that make the resumption worse, by a retard hunchback out of Lady—Don’t Turn Over by shudder pulp monsters, to get her to reveal the whereabouts of her gangster love Spike who’s absconded with the proceeds of a robbery. Eventually,

From shoulder to ankle, there wasn’t a square inch of Kitty’s body that wasn’t bruised and bleeding. Again and again the lacerating leather had torn slivers of flesh from her body. What little remained of her dress was in ribbons and caked with blood. (Ch.2)

She still heroically holds out until threatened with having her face hacked with a razor, at which point Spike turns up, settles scores with Hunchy (yes, his name) and the others, brutally rejects Kitty for “betraying” him, and leaves her and Janson, still bound, to be burned alive in the house.

Did this come out before “Scarred Faces,” or was Frances working with more unstable models? Hank is almost “stifled” with a handkerchief (not scarf) tightened around his neck. He shows no signs of being discommoded by having his nose pulped flat, his eyes probably closed, and maybe cheekbones fractured during his beating. Nor does Kitty, despite what he says about her continuing pain, act like someone who’s been virtually flayed. The dialogue is off too at times.

But if you’d been eighteen back in 1946, with tantalizingly brief allusions to Gestapo interrogations in your head, you’d have been reading bug-eyed like a cartoon teenager in 1950 up in his room with an EC comic book.

Rine Gadhart, Too Tough to Die, 1946 (Reprint of the 1942 edition)

See Violence Inc 3

Paul Renin, The Brute (1946)

Handsome popular novelist Desmond Carter has withdrawn to a tropical island and moodily boozes in low bars because of having been let down by a woman, Mona Carnforth. Who then turns up as a new “white slave” captive, having survived the shipwreck of the yacht on which she was voyaging with her husband old Lord Deslake. Desmond rescues her in a fight with a low Dago, and then (shades of The Sheik) coldly demands that she become a serving girl in his kitchen. Which she does, subduing her haughty spirit under threat of physical punishment.

But when he’s gravely wounded in another fight, she goes to his side. And when corrupt Doctor Daudet agrees to save his life in return for a night of amour with her, she agrees. And when Desmond recovers, she finds she’s pregnant with Daudet’s child, and has to confess her fall to Desmond. And Desmond kills Daudet, but murder isn’t considered a crime on that island. And Lord Deslake turns up again, and the baby is stillborn, and there’s another shipwreck, and Deslake drowns for real this time (I may not have got the sequence entirely right), and she and Desmond are reunited, and “over the sea came the first faint light of the dawn.”

Renin’s Flame, from around 1940, opens memorably with:

The last throbbing note had found its way back to the silence of that great theatre. Adam Danieli, erect and handsome as a god despite his graying hair, smiled faintly over his violin into the shadowed faces of five thousand thrilled and motionless people.

His recital, “the unchallenged act of the evening, came between the Merry Gangsters and a highly paid troupe of acrobats who concluded the programme.”

In a theatre with five thousand seats, all filled? In London?

Ben Sarto, Miss Otis Goes Up (1947) NEW

So much more controlled stylistically than Miss O’s debut that I assumed while reading it that it was from the Fifties, only to learn from Hubin’s bibliography that, along with Miss Otis Throws a Come-Back, it appeared in 1947, continuing the saga of “the glamorous Mabie [Mabel?] Otis, the smoke-sexy blondie who had spent her crowded lifetime in collecting more adventures, amorous and otherwise, than ever fell to the lot of any ten women.” (10)

In the present book (going on from Miss Otis Throws a Come-Back?), Junoesque Mabie, back in the States, scarcely needs to do or even say anything dramatic herself for there to be drama, namely her having to cope with the unfair depredations of others, and almost of life itself. Her husband/lover/ partner Granger Girton is mysteriously murdered at the outset during a celebratory party, leaving her to cope alone with ownership of a large Manhattan apartment building, along with her Otis Restaurant. An “evil-looking yellow-faced guy” (Sigmund Knieffer) barely five feet tall, tries to extract two or three thousand bucks out of her for not having her stuck with a ruinous business injunction. Admirers George K. Thoday and Carter Schooling are savagely beaten by hoods. And the Otis (Sarto’s French-derived phrasing) has to pay out big blackmail bucks to crafty old Doctor Palmer. True, this is because the Doc has found out that Schooling had throttled Kieffer after Kieffer spat in Mabie’s face. But she didn’t take part in the killing the way she did in her London venture. The novel ends with her financial ruin and Doc Palmer and his snippy lethal mistress Barbara Love still prospering.

To be continued?

So, since there’s virtually no sex, what is one getting for one’s 2/6d, I mean, you know, really getting?

Well, how about this, from the beating of big craggy-faced realtor Carter Schooling?

He staggered back with a thin scream of agony, and screamed again as the [razor] blade caught him a second time. The first slash had cut right across the cartilage of his nostrils, the second carved downwards, laying open his cheek from cheek-bone to chin. And as if this was not enough, the second attacker, an undersized youth, swung a loaded club and caught him a crushing, staggering welt on the right ear. The effects of the blow were immediately horrible, for the soft tissue of the ear was split and crushed and rushed up into a swelling as if it had been blown up with an air-pump. The excruciating agony of the blow was such that Schooling couldn’t even yell; it had taken his breath away completely. (101)

W. R. Hutton, Not a Dog’s Chance (1947)

On the front cover a suave, head-and-shoulders, dark-haired guy in evening dress, with white tie, looks enigmatically out at us, left-hand (with cigarette) to cheek, right holding a smoking automatic. Tiny margins and microscopic print. 96 pp. Price 9d.

A leisurely whodunnit / espionage novel set in the Puddenham Gun Engineering Company works, a milieu that the author was evidently personally acquainted with, to judge from the density of characterization and settings. Lots of dialogue. A “difficult” Communist foreman is presented sympathetically. There’s quiet ironical comedy with the manoeuvrings between cops (one of them particularly dense) and bosses.

The cover image is unrelated to the contents.

James Hadley Chase, No Orchids for Miss Blandish (reprint) NEW

No Orchids (1939) exists in at least five different texts (see Sidebar 1, Afterpiece 5.) The reprints during the Jungle years would have been of the 1942 Jarrolds text, revised by Chase himself. The book was reprinted in 1947 and 1949 in hardcover and in 1950 as a paperback. Probably a number of Jungle writers knew the original text.

The book is simply the most powerful and best written of all the Jungle gangster novels. Have I read them all? No, but what one might be better.

In his 1944 polemic against it in “Raffles and Miss Blandish,” George Orwell called No Orchids “a brilliant piece of writing, with hardly a wasted word or a jarring note anywhere.”

It had the advantages of a classic situation, a clear story line, distinctive characters, and no shying away on the author’s part from the unpleasantnesses that one feels emerge naturally from the almost uniformly unadmirable characters.

A couple of minor hoods, Bailey and Riley, kidnap beautiful redhead Miss Blandish (no first name provided), daughter of a millionaire meat-king, after a dance to which she wears a very pricey necklace. Slim Grisson, depraved son of gangleader Ma Grisson, kills Bailey and Riley and takes Miss Blandish back to the gang’s headquarters, where, Ma beats her with a rubber hose and starts her on dope to soften her up as a sex-toy for Slim. Ma also picks up half-a-million bucks in ransom money, using a chunk of it to set up a fancy nightspot.

The cops having got nowhere, Daddy hires tough shamus Dave Fenner to search for Miss Blandish, which he does with violences along the way, culminating in the successful police third-degreeing of former gang member Eddie Schultz. Slim makes a getaway with Miss Blandish before the cops blast their way into the gang’s headquarters. After the cops gun down Slim and return Mss Blandish to civilization, she throws herself out of a hotel window.

Pain is for real here. We feel it when Bailey socks Miss Blandish’s frat-boy escort across the face with a cosh, and Slim slowly pushes his switchblade knife into the bared belly of Bailey tied to a tree, and Ma slaps Miss Blandish silly, and her screams while being flogged reach the living room, and Eddie Schultz is tortured in the police basement.

They jerked his head back by his hair, and one of them hit hm across his bared throat with a club. He hit him very hard. Eddie suddenly stiffened, straining at the straps. The chair creaked with his movements. He jerked and pulled while he fought to get the air into his lungs. His face was blue with the effort, and for a moment Fenner thought he wouldn’t make it. They stood back and watched him have his convulsions.

See Note 33 on actual third-degreeing.

But the central kidnap-and-rape situation isn’t just a pretext for violences. Characters reach ahead, and what happens is plot-driven and psychologically credible. It also all has a gritty, grayish Thirties feeling. There’s not much sensuality, and very little sensuousness. People aren’t eating, drinking, and dressing well, or at least aren’t described as so doing. The mind’s eye doesn’t immediately fill the Grissons’ nightspot, movie-fashion, with tuxedos, backless satin gowns, and champagne cooling in buckets. There is almost no humour, and not a trace of the playful side of Jonathan Latimer, whose Bill Crane novels were more important for Chase than The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Not everything in the novel is a savage power-struggle. In “Some Orchids for James Hadley Chase” I disagree with Orwell about that. But Chase is telling it all for real, and without any catering to a “sub-literate” market. The book was unprecedented in British fiction, which did not prevent it and the play developed from it from being very popular in wartime Britain.

The book was never prosecuted. Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief (1941) was the work that landed Chase and Jarrolds in the dock at the Old Bailey in 1942, along with Harold Kelly and his publishers. “Darcy Glinto’s” unabashed 1940 reprise in Lady—Don’t Turn Over had the erotic intensity that No Orchids lacked.

Miss Callaghan was withdrawn from circulation and has never been reprinted in Britain or North America.

Buck Toler, Tough on the Wops (1947)

Lovely, shy Italian-American Francesca sets out to avenge the gang killing of her young restaurant-owner fiancé Angelo who refuses to pay protection money. For more details, see Note 23.

Darcy Glinto, Curtains for Carrie, 1947

The first Glinto in six years.

Beautiful 19-year-old Carrie Donovan carries on her father’s coastal rum-running operation when he’s executed after being tricked by greasy, lecherous, would-be big boss Poulos, for whom she and her tough all-black crew make business and life increasingly difficult. Peter O’Donnell must have known this one.

We’re told at the outset that she’s shot to death, so after awhile we start wondering, Is this the point where she makes a bad decision leading to her death? Is it this? This?

Darcy Glinto, Blue Blood Flows East (1947)

Fast-living Manhattan socialite Rosa Van Sennes becomes emotionally involved in the dangerous business affairs of gangster Garry Banner.

For the plot of this, after a point, almost unbearably suspenseful narrative, see Note 22.

No Come Back from Connie (1948)

The leaders of two rival gangs, Connie O’Mara and well-born Pen Lupin, are locked in conflict despite or because of the strong sexual attraction between them. Peter O’Donnell must have known Connie, with her strong spirit of independence, her unpanicked coping with a seemingly hopeless captivity at one point, and her use at another point of a version of the Nailer.

William J. Elliott, Snatched Dames (1948) NEW

Some very violent bits in a book that mostly doesn’t feel as tough as it purports to be. A reprint of the early Forties edition, in which the author was obviously getting in on the market opened up by Darcy Glinto in Lady—Don’t Turn Over, No Mortgage on a Coffin, and Snow Vogue. See Note 63.

It’s described in an ad in T.W. Ford’s Redemption Trail as, “The toughest of tough gangster yarns—certainly not for the squeamish.”

Michael Storme, Unlucky Virgin (1948)

Difficult, well, next to impossible to believe that this and Hot Dames on Cold Slabs (see below) are by the same hand.

Unlucky Virgin would have been a strong read at the time and still has life in it.

Fiancé John Laramie goes West from Chicago to make some money. Fiancée Mary Glynn, staying behind, is introduced by a woman friend to nightclub life, where she becomes acquainted with gangster Mike Skellon, who takes her on the lam with him when there’s gunplay, and from whom she’s grabbed by bigger-fish Butch Steggles, and kept as virtually a prisoner for awhile in the country under the watchful eye of an underling, with ahead the unsavoury prospect of life in a “sporting house” on an island, in the direction of which she’s finally taken by boat, after which John, who’s been searching for her in an interwoven narrative, turns up before she’s inducted.

She’s a spirited lass who’s not afraid of guns, improvises a cosh with a heavy lighter in a bit of blanket, tries escaping through a window with knotted strips of blanket, and isn’t broken up on the two or three occasions when sleeping-with becomes unavoidable, one of them after accidentally doping herself with some offbeat cigarettes.

There’s a sufficiency of gunplay and killings, but the basic shtick is that on several occasions she’s alone and in the power of men who may, if she isn’t lucky and/or careful and/or resolute enough, rape her. Her situation on the boat with four hoodlums brings to mind the two final chapters of Jonathan Latimer’s The Dead Don’t Care. And the madam of the sporting house in which she may end up is called Ma, as in No Orchids. And a fan-dancer who jettisons her fans before the end of her act feels like an extrapolation from Cora Bilt in Lady—Don’t Turn Over.

But everything’s made less than lethally sharp-edged by a British-type prose.

She struggled wildly as his clutching fingers grasped at her arms. “Please don’t!” she pleaded again.

As he pressed his thick lips into her neck, she lashed out at his shins. He howled and let go his hold. He then laughed admiringly. Again Mary pleaded with him, but her pleas fell on deaf ears. The man’s rough hands bruised her soft skin as they caught at her again.

He smacked her heavily across the face. Then his face pushed close to hers and his thick lips bruised her mouth. Mary struggled wildly, and gazed in search of some weapon. She cursed as she noticed everything of a movable nature had been fastened down ready for a voyage.

Her roving eye fastened on a heavy-looking bulge in Movanti’s pocked. “I wonder,” she mused. “Could that be a gun?” (66)

She does in fact shoot him, not fatally, but is overpowered, after a bit more shooting, by the other guys outside the room.

Later on, when reminded that “Yuh weren’t so cold when yuh were doped” and that she’ll probably need doping when she’s in the sporting house (echoes of No Orchid),

“For goodness sake!” Mary said irritably. ”Don’t bore me with your dirty reminiscences. One of these days you’re going to be sorry for kidnapping and laying your filthy hands on me. Oh boy … am I going to enjoy seeing you get yours!”

(A faint echo of the end of Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief?”)

But the book has the requisite narrative substance and suspense.

How could this be by the author of Hot Dames on Cold Slabs?

Unless, I suppose, after being told that he needed to jazz up his style and make it more American, he went, tongue-in-cheek, way up over the top.

Unlucky Virgin contains the following note:

To Peter (Lofty Reynolds who struggled manfully under the African sun correcting the proofs, and to other comrades in the Royal Air Force who made useful suggestions—even though they were my most exacting critics—I dedicate this book.

Travor Dudley Smith, Now Try the Morgue (1948) NEW

The writer has obviously steeped himself in works like Hemingway’s “The Killers,” Hammett’s The Glass Key, Edgar Wallace’s On the Spot, Paul Cain’s Fast One, and Chase’s No Orchids and The Dead Stay Dumb. He seems to have become American, and relish speaking and “being” American—in his own fashion.

At the centre are two buddies, hitmen Al Gillespie and “Raz” Berry. Raz, a hard drinker, is smitten by l’amour fou in a nightspot and makes a pass at the mistress of smiling ruthless Point City boss Kone, whose two henchmen immediately beat him up and put him into hospital with his memory gone. After which, Al and a couple of floozies have to keep him away from Kone lest his memory and obsession return.

Also, Al, carrying out a contract with her uncle, has hit a lover of rich divorcee Moyra Crawley, who contracts with hitman Toller to take out Al. Al, seriously wounded in the arm, plots with Raz to take out Toller, but Toller is close to Kone, whom Raz mustn’t see …

There is no consequential police presences.

The author has opted for the kind of slang-dense prose that Dashiell Hammett had eschewed, making Hammett’s works less vulnerable to the erosions of time. A doctor is a “stitch,” a brain a “grey,” a brothel (or is it a cheap dance-hall?) a “hip-joint.” But he does it with conviction and. I’d say, carries it off, reinforcing the feeling that we’re inside that the Weltanschauung of a couple of guys who happen to make their living with “contracts,” and not viewing them from outside as specimens of something or other. So even when nothing dramatic is happening, the narrative isn’t noir-bleak and depressive, partly because of the writer’s ability to shape paragraphs and his feeling for how minds work.

Here are passages that I liked.

(a) “You’re a swell guy,” she said when he’d kissed her good-night.

She meant it. [Krone] knew she meant it. He knew when people lied to him, or flattered him, because about ninety per cent of his associates did that. So he knew when someone told him the truty all right.

“Night, honey,” he said and left her at the door of her suite. (27)

(b) Raz wasn’t feeling so hot, at that. He thought there was an air-bladder blown up plenty tight somewhere inside of his head, and there was a sort of high buzzing coming from somewhere, back of the blue light. Everything was blue and he was shooting through it all like he was a rocket; the bladder was getting smaller, and he knew there was a funny taste in his mouth. The blue light went out suddenly, and he couldn’t see anything for a little time, until he saw three posts, he didn’t know what the posts were doing there; now the blue light had gone.

“Hello, Raz,” said Al, softly. (40–41)

(c) He looked at her close, and said:

“You know, Carole, you’re a cool sorta girl, at that. D’you like killin’s or somethin’? Don’t I stink of blood or nothin’, straight back from a rub off?

She smiled again then and said slow, so only he heard:

“Listen, Raz. The burg I come from’s a slaughter-house compared with Point City. Guys just go gunning each other like there was a war on. It ain’t healthy, but at least it gets a girl used to the way things go around this part of the globe. You don’t stink of blood any, you just come back from business, that’s all. Is that normal?”

“Snakes! I think it is. I gotta get the [amnesiac] hang of things, I guess.” (71–72)

Here, finally, is rich up-from-the-gutter Moyra Crawley lying in bed and recalling Al’s killing of Nick Berger:

Some guy’d looked in at the car window while Nick had been caressing her; he’d held a gun into Nick’s chest and he’d given the trigger a little squeeze. She remembered how the blood came in a little trickle out of the corner of Nick’s mouth. His hand had stopped caressing her, because there was nothing to make it move then, no master-influence. So his hand had stopped and was still. Half an hour after that, when she’d come to from under a faint, his hand was still there. And it was cold and stiff. She’d thrown it off in horror. Why? Wasn’t it Nick’s hand? The loving hand of a nice kid who took her places and gave her a good time? Just because he’d been dead half an hour, the icy touch of that hand brought, not ecstacy, but horror. Queer how things went. Death was queer; dying was natural, but death was queer. (101)

There are two authorial names on the title page of my hardback Gerald G. Swan copy, the second one, in parentheses, being Elleston Travor, who later metamorphosed into, among other things, Adam Hall, who gave us the glorious The Volcanoes of San Domingo and the Quiller books. I have the feeling that there are continuities from Now Try the Morgue.

Ace Capelli, Get Me Headquarters (1949) NEW

A thoroughly unpleasant gangster, Joe Keefe, having decided to leave for England before the cops catch up with him, sends his mistress off in a car with a couple of his hoods, who tell her along the way that this is her last ride. After pushing her over the edge of a cliff,

Neither man moved except when once she looked as though she might claw her way back to safety and then Duval stepped forward and brought his heel down savagely on her fingers. They stood there watching while the strength went from her arms, watched as she slid backward, slowly, slowly, her arms flagging, her fingers bleeding, digging into the ground. They watched until her arms slipped from the edge of the cliff and only her fingers held and they still watched as the fingers lost their strength and finally released their hold. And they watched without emotion, watched as sanity changed to madness in the girl’s eyes, as life changed to death. Then they listened as the long scream went hurtling on to the sharp rocks two hundred feet below and stopped abruptly. (p.31)

I find that more disturbing than the violences in James Hadley Chase and Darcy Glinto.

The gangster has himself shipped across the Atlantic in a crate equipped with all the necessaries—except that he’s in there six days longer than expected, because of a strike, and arrives with his left arm gangrenous and stinking, because of an untended cut on his hand. The amputation of his forearm is described in detail. But after his recovery, he is able to apply American gangland methods successfully in London.

In the last part of the book he makes a girl who has dissed him his house slave, frequently thrashed with a belt.

The book was probably disturbing when it appeared, and I still find it disturbing. But it isn’t, so far as I can see, conventionally sado-masochistic. There isn’t a shared enjoyment with either the tormentors or the tormented. The best take that I can manage is that the author is acutely sensitive to pain, physical and psychological, and accepts the reality that some people who enjoy inflicting it are absolutely without any sympathy with their victims and hence cannot be appealed to in any way. Which I am sure is true, but I’m not sure where, if anywhere, he goes beyond that.

Harold Kelly, writing as Darcy Glinto and, in Tough on the Wops, as Buck Toler, is unusual among the Junglies in his empathy with women as individuals and agents, not simply victims. As I have said elsewhere, he is concerned, where both men and women are concerned, with modes of self-affirmation and resistance to oppression. Bad things can and do happen—but not inevitably, and confinement of one kind or another is not the predominant reality.

Why is the cliff passage here more shocking than the episode in Nat Karta’s Love Me Kill Me that I describe?

In the latter the narrative is wider-angled. The anonymous thirtyish woman is herself a risk-taker, hitchhiking at night and making the pass at the trucker that takes them off into the bushes, where they witness a murder. Her involuntary scream gives them away, he’s killed, and she is raped, knowing that they’ll kill her afterwards because of what she’s seen. The killing of her is quick and practical, a blow to the skull.

Here, in Get Me Headquarters, we have only the intense concentration on the victim’s terror and desperation, the futility of her efforts, and the unreachableness of the two men, as if watching the hopeless struggles of some small animal.

Darcy Glinto, Lady—Don’t Turn Over (1949)

A reissue, slightly bowdlerized, of the white-slavery-and-blackmail novel extrapolated in 1940 from No Orchids for Miss Blandish and withdrawn for circulation in 1942, along with Chase’s Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief and Glinto’s Road Floozie, after the 1942 trial at the Old Bailey in which publishers and authors were heavily fined.

Clare Holding, daughter of FBI chief Grover Holding, is kidnapped by Dill Slitson’s gang and flogged by drunken hunchback Min (Minnie?) with a rubber hose to make her want Slitson.There’s a strong subplot with stripper Cora Bilt, Lynx Hansen, and a senescent sugar-daddy. The third-degreeing of Hanson is even more violent than the one in No Orchids that disgusted George Orwell.

Reissued with some further changes in 1952. For more about the original version, see Sidebar 3 and Sidebar 8: Scandal.

Roland Vane (Ernest McKeag), Night Haunts of Paris (1949)

Despite the elegant pimp on the cover beating up a couple of girls, this is a sensible tourist guide to sexy Paris. . There’s an intriguing reference to lowlife establishments where, “behind closely and tightly shuttered windows and sound-proof doors, the cult of the decadent is given full rein,” so that “The happenings in these nefarious establishments are of such a nature that they cannot possibly be described in print.” (p. 52) But this is essentially the cleaned up and strongly policed post-war Paris of the Loi Marthe Richard abolishing brothels. Vane seems knowledgeable about the socio-economic dynamics of prostitution and the more liberal atmosphere of pre-war Paris. Presumably his White Slaves of New Orleans, advertised inside, is more of the same. Almost thirty other titles stand to Vane’s name in the British Library Integrated Catalogue.

Hank Janson, Lady. Mind That Corpse (1949)

Hank, who’s drifting around the country, becomes involved in a Denver power-struggle between Doone (cruel stepfather of Sheila) and Mullagawny (somewhat less bad) with the help of Patricia, who near the end hangs by one wrist as a thin wire is tightened around her thigh until it cuts into it “like it was cheese,” while someone else’s hand is pinned to a table with a knife. Prior to these characteristic Janson touches, the B-competent novel is generic, with familiar elements and no particular highs or lows.

“About the Author” on the back is more inventive:

Hank Janson tells us that he was born in England during the Great War.

When he was nineteen, he stowed away on a fishing trawler and started on an adventure which was to last until 1945. Not once during the intervening years did he come back to England. He has dived for pearls in the Pacific, spent two years in the Arctic with a whaling fleet and worked his way through most ot the American States. He worked in New York as truck driver, news reporter and as assistant to a Private Detective Agency. During the war he served in Burma.

Two years ago he returned to England and is now living in Surrey with his wife and children.

His life has been rich, exciting and dangerous—and almost it may be said, as true to life as his stories.

When Len Deighton hit the street in 1962 with The Ipcress File, one learned, fictively, from the dustcover bio that he had for a time been the equivalent of an Air Traffic Controller in one of London’s main train depots (Clapham Junction?). Cissy things like his time at the Royal College of Art and at an advertising agency went unmentioned.

It never hurts to know, well, believe, that thriller writers have displayed in the real world some of the qualities of their heroes.

Roland Vane, White Slaves of New Orleans (1949)

Seventeen-years-old village girl, “long-limbed” Shirley Westford is conned by motherly old Margaret Gratz into coming down to New Orleans to be her companion, where she finds herself in Joe Gutterman’s brothel, penniless and with no-one to turn to.

The breaking down of her resistance is relatively gentle—bread-and-water up in the attic, a stint of servitude to a low-life down in the bayous. She settles into the brothel routine, misses a chance to escape with young seaman Jimmy, becomes the mistress of crooked Cal Wheeler, gets hold of papers that enable her to blackmail him, sets up as a madam herself, makes a shiftless aristocrat marry her, travels with him in European circles, meets Jimmy again, now Sir James. Blackmailed by a scumbag from earlier in her life, she falls with the scumbag to her death off Sir James’ yacht.

It’s a novel of character really, covering a number of years. A woman fights back and triumphs, up to a point over adversity. It might almost be an unsexy adaptation of a turn-of-the-century French yellow-back novel. The two or three rapes aren’t described. There’s no significant nudity.

Hank Janson, No Regrets for Clara, London (1949)

Another of Janson’s pain-and-subjugation narratives.

Hank, not yet a journalist, is trapped on a cabin cruiser (equipped for tuna-fishing!) that’s out of gas on Lake Michigan with a cargo of three good guys and a couple of goodish girls who are now at the mercy of four hoods and a moll who’ve made a getaway after a bank robbery with a lot of money and a gut-shot leader. Jed, who takes over after Mike dies, is a sadist.

Hank, Lanny, and the two girls are set (somewhat improbably) to rowing the boat towards Canada with improvised oars and rowlocks, their wrists tied to the oars and their backs lashed with a rope’s end whenever exhaustion and the state of their hands slows them down. Clara and Dora, in skimpy summer dresses and the flimsiest of underthings, are obvious targets for rape. When the tables are finally turned, Clara lashes her abuser Jed’s back into a bloody pulp, with probable damage to his kidneys, so that he screams in agony afterwards at the lightest touch.

The name Dopey for one of the hoods obviously derives from the final episode in Jonathan Latimer’s The Dead Don’t Care, in which detective William Crane and a couple of other good guys, along with the young fiancée of one of them, are bound hand and foot aboard a cabin cruiser occupied by hoods with murder and a little raping on their minds.

N. Wesley Firth, When Shall I Sleep Again (1950).

Not strictly speaking, a “jungle” book, being hardcover and a Thriller Book Club item. But it’s the only novel that I’ve been able to access by the author, among other things, of This is Murder, Lady (1945) and Broadway Doll, Dames Play Rough, Studio Revels, and Lady in Leicester Square, all 1946.

A conscientiously-crafted 239-pp. noir. The basic situation is extrapolated from The Postman Always Rings Twice and fleshed out, without actual pastiche, from the interior noir landscape of fiction and movies. A characterless young guy, Eddie, driftingly on the run, finds sanctuary as a chauffeur-handyman with a rural New England, at least I think it’s New England, doctor and his wife Sylvia after being struck by the former’s car.

Sylvia is bored, sexy, avaricious, ruthless, and homicidal. But these traits are not all manifested at once, and the road to disaster for Eddie and herself has various curves in it and is traversed somewhat leisurely. The book would probably have been considered in the British sense a Good Read. Personally I found it depressing in the usual noir fashion, since you know that things are going to go badly for everyone. But it is textured enough not to be skimmable.

N. Wesley Firth (1920–1949) was a real person, although the middle name was an addition not consistent with birth records. He added it after his father, Henry Wesley Firth.—SH

William J. Elliott, Freak Racket (1950)

The reissue of a 1941 novel about uncovering the deliberate creation of freaks in a tropical laboratory. Opens with a replay of the opening of Lady—Don’t Turn Over (hoodlum and humiliated dame in car), and contains strong violences along the way. E.g.,

I pulled a bowie out, and yanked him out of bed. I got my hand in his crimped hair and pulled his head back. He startled to yell, but it turned to a choke as the knife went home. It made a sort of plunking noise as it perforated the taut skin. Then I gave it a twist and cut like a butcher. By the time I’d done there was as much blood about as there’d been with Susie …

For more about the novel, see Note 42.

The victim had killed Susie in the same fashion.

Darcy Glinto, Road Floozie (1950; first edition 1941)

The expurgated reissue of a novel withdrawn from circulation in 1942 after being found obscene in Britain’s highest court. Young, independent-spirited Eilleen Rourke quits an exploitative garment workshop job for the open road, drifts into truck-stop sex-for-pay in order to survive, and starts killing truckers after being viciously raped by a pair of them. An “existential” novel a year before Camus’ L’Etranger, but there are human decencies and real-feeling relationships, and it’s not bleak or bitter. The original text absolutely has to be reprinted.

See also Sidebar 3.

Hank Janson, Torment for Trixie (1950) NEW

A readable narrative that feels like two separate ones linked together artificially. The first half, more or less, is a mild comedy in which ace-reporter Hank is told off to get a story about the author of a first-book sexy bestseller. Which involves him in introducing to the delights of the big city—cocktails, restaurants with menus and wine lists in French, night-club shows, hangovers—a virginal Plain Jane romancer from an ultra-square small-town family who persists in denying that she’s the novelist.

The second half lands them in the clutches of a ruthless gang counterfeiting hundred-dollar bills in the zillions, with an island base and a talkative master-mind assisted by Jap underlings in their native costumes. Hank is lippy and tries punching out baddies, only to be knocked out and tied up. Trixie at one point hangs, bared to the waist, by her wrists and is lightly tortured, with white-slavery mentioned as a destination. Finally Hank liberates them both, with the help of a bit of optical gimmicry that I don’t think would have worked. The narrative tone throughout is not particularly worried, and we know that things will turn out OK for Hank and Trixie. The title is pretty much a come-on.

Hank in these early series doesn’t seem to me a fully developed character to set beside other series narrator-heroes like Philip Marlow, Mike Hammer, Shell Scott, and Travis McGee. This may be partly a consequence of the books being relatively short (though Hammett’s Op has character enough in the short stories). But I would guess, also, that, given the stream of Jansons from his typewriter, Frances had to keep Hank relatively open, so that he could be, in different contexts, cynical Hank, brave Hank, klutzy Hank, lecherous Hank, chivalrous Hank, and so forth.

And since readers would have pretty quickly grasped that Hank would be as bouncy, mildly voyeuristic, and unencumbered as ever at the start of the next book, they could be confident that nothing really bad would happen to him, and that he wouldn’t have Trav’s recurring problem of rescued dames and damsels gratefully imprinting on him and having to be killed off. Hank in these early books doesn’t really come across as much of a, to use Ross Thomas’s term, cocksman?

The Hank of later novels like Reluctant Hostess (1961), Honey for Me (1962), and Sex Angle (1964) has more substance, but by then other authors were also using the Janson name, and I’ve opted for those three particular titles, on internal evidence, as being by Harold Kelly. See Sidebar 5: Darcy Janson.

Spike Morelli, Coffin for a Cutie (1950).

A live one. A first-person “Southern” novel, with young white-trash guy fleeing the swamps with a black friend (who’s subsequently murdered) and taking up small-time crookery as photo-blackmailer. Several women are involved along the way, not to their benefit. There’s a sexy nightclub show, and a nude with a mutilated face swimming at night.The narrator has no problem with hitting, beating up, sleeping with, or in one instance shooting women. The style reminds me a little of Boris Vian’s I’ll Spit on Your Graves. The atmosphere is mostly unquiet, the course of events unpredictable. The book feels as though the author had been in the States . Six other titles are listed in BLIC, This Way for Hell isn’t among them.

I wrote the foregoing without knowing that Morelli was Frances.

Spike Morelli wasn’t Steve Frances, it was William Simpson Newton.—SH

[NEW] In 1983 a revised version of this was published over William Newton’s own name as Don’t Hold Your Breath, and reprinted in 1992 as one of a dozen titles by him in the large-print Linford Mystery Library. Cultural allusions are updated (Elton John, video, etc). The narrator’s violences are toned down here and there (e.g., instead of killing a gas-station kid who was going to turn him in, he has him drive them away and then turns him loose). A sexual relationship with sister Anna is added. Male dancers in a voodoo show have lost their g-strings and acquired erections. Natural settings at times are more lyrically textured. The ending is fuller. Here are the opening paragraphs of the two versions:

It was a hot afternoon in mid summer and I was hanging around the edge of the swamp waiting for Will. Sunday was my day. The rest of the week I worked in the store for my uncle Jesse Case and didn’t have much time to fool around. Sunday was different. I had the whole day to myself and did just what I liked. [Coffin]

I reckon it all began on a hot afternoon in mid-summer. I was waiting near the edge of the swamp for Will to show, and becoming increasingly impatient as the sticky heat began to get to me. Sunday was always my best day because from noon onwards I had time to myself to do whatever I wanted. All the rest of the week I had to work for m uncle Caleb Calder and there was never any spare time to fool around with anything. He worked me from dawn to dusk almost without a break, and his voice bellowed at me if I tried to park my ass even for a moment. [Don’t Hold Your Breath]

Michael Storme (George Dawson) Hot Dames on Cold Slabs (edited by Lewis Thompson), Leisure Library (New York), [1950, BLIC]

A memorable example of optimistic incompetence. Anyone, it appears, should be able to write an American novel.

Three nice girls arrive in Chicago from the country and hook up with guys, two of them gangsters. Nightclubs, cars, bedrooms, undressings, confrontations, beatings, shootings, leerings. An America of the mind.

“Here’s to us,” he grunted, his voice thick with temporarily controlled passion, but with uncontrolled fingers kneading the flesh of her thighs.(p.34)

Blood cascaded down his puffed face as one of the hands came across his nose in a snappy cross movement. (p.37)

Bared to the navel, once firm breasts staggered through the torn folds as if coming up for air.(p.48)

“Guess I do recalls a tha name, honey Takesa pew.” (p.51)

“Leave me alone,” she grunted. “A murderer … ugh!” (p. 61)

Teeth crunched as his heel changed Moffin’s face into a shapeless mass, then Martin was diving for the fallen gun, grasping it lovingly with deliberate intensity.” (p.75)

Martin thrust the pulsating motor more gas.” (p.77)

The threat dripped from his mouth like from the jaws of a belligerent tiger.” (p.81)

He would go out with holes in him big enough to allow the whole of his inside to discolor and ruin whatever carpet he may be standing on at the time. (p.86)

A clucking sound of obvious displeasure dribbled from his mouth along with a slight foam.” (p.89)

There’s a doping-the-recalcitrant-girl bit from No Orchids and a setting-fire-to-the-stuffing-of-a-mattress bit from The Glass Key.

According to Maurice Flanagan, in British Gangster and Exploitation Paperbacks, Storme’s books were very popular.

At the back , Jules-Jean Morac’s No Prude, Spike Morelli’s This Way for Hell, and Roland Vane’s White Slave Racket are announced as forthcoming.

Duke Linton, Crazy to Kill (1950; reissued as Frank Corbett, Trouble with a Woman 1964)

The summary narrative voice describing the murderous competition between three brothers for a woman could easily be mistaken in places for Glinto’s. But it is coarsened and fragmented in others, and there are hinted-at sexual depravities that you wouldn’t find in Glinto, and you know from early on that the hopes of the best of the three brothers for happiness with Clara are doomed.

By Stephen Frances. Also published as Wild Blood by Darcy Glinto.

Duke Linton, Too Late for Death (Scion, 1950?)

The author of this can really write, meaning he can make things come alive in front of you, and because the individuals involved feel real and self-motivated, things don’t proceed along well-worn channels when it comes to details.

Johnny Swisbeck, “old-time bank robber,” busts out of the Oregon pen and unhesitatingly shoots persons who get in his way, including his escape partner, whom he shoots in the back while he’s raping a farmer’s wife. He also makes mistakes, and gets grabbed by bad guys and almost drowned when a truck driver backs him off the edge of a wharf. Real-feeling dialogue, real-feeling evocations of being in cheap eateries, in one of which watching a hamburger being made gets a paragraph to itself. Convincing cruelties—young gangsters pushing a punch-drunk fighter around, a woman (recalled by journalist Kelly) who’s suspected of two-timing: “Laying on the floor stark naked, her face branded with an iron on both cheeks. Her face and buttocks too. And not an inch of flesh without ribbons of thin blood marks where she’d been beaten with wire.” (p. 93)

But also moral delicacy in the relationship between Johnny and Stella, whom he picks up hitchhiking, and from whom he doesn’t seek sex, and cries later, after being given fifty bucks (a considerable sum then) to help her on her way.

She was small, and may have been good-looking, but her face was thin, blue with the cold of the wind, and there were deep black rungs under her eyes. Her clothes, Johnny saw, were torn in several places, and she was shivering and gasping with the effect of the wind and the cold rain. Her shoes were broken, and the wind blew her light coat and skirt billowing upwards to reveal her white legs marked with bruises. Her lips were cut and bruised.

The writing thins out when Johnny reaches the city where he plans to take revenge on the hidden Big Guy, as if the MS had to stay within the almost obligatory 128 pages.

According to Flanagan, Linton was a Scion house name used by Stephen Frances, Frank Dubrez-Fawcett, Vic Hansen, and Norman Lazenby. It seems to me beyond the abilities of Frances and “Ben Sarto” at that time. I haven’t been able to access anything by the other two writers. Occasionally I was reminded of Glinto.

Duke Linton, Too Late for Death, was Frances.—SH

Michael Storme, Dame in My Bed (1950) NEW

Generous-spirited.

Unabashedly reprises the start of Farewell My Lovely, but with jazzy heightenings, beginning with:

When a guy with scads of dough in more’n six banks gets around to sending for a private-eye, he either sends a letter headed with enough gilt letters to float a loan, or he sends a Queen Mary of a car with a chauffeur and a very polite: “I wanna see you bud!”

So Chicago shamus Nick Cranley goes out to the Bollard home, and there’s, yes, a butler, and, yes, an oversexed sister (Elvira) who flings herself at him, but when he gets into the inner sanctum, it’s sexy blonde stepmother Danger who’s awaiting him with the problem of feckless stepson Peter who’s into debt with gamblers and has now vanished, along with a map of uranium deposits in Papa Bollard’s safe. After which Storme starts cooking.

There’s the murder of nightclub owner Peter Marvin that looks as though the other Peter dunnit, and predators in search of Peter and, absent him, information from Nick, notably gambler Mike Arran, whom Peter is into for a hundred thousand clams, and curvacious Karta Drucker, who has no problem toasting with a lighter the soles of Peter’s feet when they catch up with him. And Fat and Butch try to drown Nick in Lake Michigan, and Arran resorts to some unfriendly persuasion:

The heat from the cigarette seems hotter by the second. My lids have closed automatically, but they’ll be no protection if he jabs the cigarette on them. I wanna be tough … I am tough, but I can be “tendered” up. I have wild thoughts of how handicapped I’ll be finding my way over a swell shape and having to rely on touch alone. I like to look at curves as well as touch them. (59)

And other business, including some sexual rapture of the order of:

As Elvira raises herself to put her arms around my neck, I hold her close and our lips meet in a searing, burning kiss. Hot water runs up and down my spine; electricity is in my palms along with sweat. Her cute little tongue is probing my mouth again, and this time I think I like it as we swap chews. Time passes unheeded. Swell time. (17)

Nick has the assistance of crack-shot fellow shamus Mike Finando, and the good-will of Police Chief Brandon, and isn’t bothered by being knocked out at least four times, and gives as good as he gets in brawls, so it all comes out more or less OK at the end. But I don’t have a grip on the plot, despite two or three pages of exposition by Nick towards the end, since the author slips important narrative details into his mostly short paragraphs without sign-posting. Still, Chandler reportedly didn’t have all the answers about Farewell My Lovely when Howard Hawks was filming it.

Author? Is that Dail Ambler, by any chance? I have a genuinely bad memory for names, which makes it easier for me to read without preconceptions.

No, I see it’s George Dawson, who has over thirty titles to his credit.

Though only 128 pages of small type, the book feels longer, because of the abundance of incidents—much more than would be needed for merely cobbling together a sellable pastiche.

This isn’t hackery.

I also see that I’ve described four other Storme novels. Hot Dames on Cold Slab clearly has to be either by someone other than Dawson, or by Dawson having fun. I won’t revisit Make Mine a Harlot to see if I was being unfair. Not now, anyway.

Dale Bogard, Lead Her Gently to the Grave (1950) NEW

Private-eye and author Dale Bogard is having a week’s vacation in New Orleans.

I had come out of a little tonk near the old Cairo Hose on Franklin Street where a mixed white and colored band was playing New Orleans jazz of the kind you dream about. I walked down to Conti and turned right into Basin Street, moving towards the Southern Railroad terminal and taking it slow and easy because the air was warm and a little humid after the bracing uplift of Manhattan. I had braked myself pretty much to a standstill as I came level with the Mahogany Hall which Lulu White called her mansion until the sporting houses folded in the big red light clean-up of 1917. (6)

An odd-looking figure runs away from an abandoned house, Dale snoops into it, a lovely young brunette lies there dead (shot), a beat-cop finds Dale standing over her, and tough Detective-Lieutenant Jussac interrogates him at Headquarters, where cool Captain Beauregard is unpersuaded of his guilt. The body is that of Cecile Lamonde, of old New Orleans money.

Dale starts probing, calls on Cecile’s lovely sister Corinne, is visited by petite gunman Al Zenger who orders him out of town at gunpoint, buys himself a Luger, questions questionable lawyer John G. Arpels, takes sexy Corinne to a club, and gives us the lwords of “Yellow Dog Blues,” remarking that “the singer didn’t bawl it the way Billy Banks used to do, but I liked the way she went to work.” Nice to find someone knowing those cult-classic Banks recordings with Henry “Red” Allen, Pee Wee Russell, and others. Nice to have a New Orelans with the sounds of jazz in it, in contrast to that pretentious leaden “serious” novel about Buddy Bolden in which you never hear a single note.

(Incidentally, despite the enduring urban myth about Bolden’s lost-forever sound, we have Bunk Johnson on record—Bunk famous for his musical memory, though not to be trusted autobiographically—whistling very precisely for over three minutes a number as he recalled Bolden playing it.)

The action heats up, with Dale caught with another body, and a couple of cops eager to beat confessions out of him, and curiously simpatico but still immovable little Al Zenger imprisoning him in a log cabin while important issues are settled elsewhere. And you care, or at least I do. The denouement is more complicated than I’d expected, though I’d glimpsed, or at least had my suspicions about, one element in it.

On the page opposite the title page page we’re informed that Bogard is also the author of Lay That Dame on Ice, The Loveless Die First, Send Me No Lies, and Speak Softly to the Dead (in preparation).

Spike Morelli, Take It and Like It (1950)

On the front cover is a girl tied at ankles and wrists to a straight-back chair, her backless green dress almost falling off her breasts and barely covering her stocking tops. Behind, pulling on the rope fastened to her right wrist is an older man with the kind of brutish face you used to get in pre-Code Hollywood movies about the Big House, or representing criminality in Laurel and Hardy movies. Below: “By Spike Morelli with the gloves off.” Published by Kaywin, Cleveland, from Hanley Archer Press text.

What a gyp!

In a narrative in the flattest prose, an American crook called Raza holes up in a run-down building in Los Angeles, where he becomes friends with an artist, André. Peering through a peep-hole that he’s made in the studio wall, Raza becomes infatuated with André’s nude model, young Maria. When the cops turn up on his trail, she runs off into the country with him, and they become involved for a bit with Farmer Joseph and his idiot son. Back in the city again, she’s hit by a car and hospitalized, and Raza takes off on his own. Eventually the two of them get together again. Chased by more cops, Raza falls from a roof to his death.

Apart from Raza’s branding on the cheek a woman who’s betrayed him to the cops, and a fight with Farmer Joseph’s son, this isn’t a violent book. Nor a sexy one, either.

Here’s a sample of the prose, picked literally at random:

“You have been running,” he said, more to start the conversation than anything else.

She nodded. “Yes, I was coming home feeling very sorry for myself because I couldn’t come up and see you, when I saw André and his wife come out of the house and walk away in the opposite direction. I ran all the way to you, Alex.”

“You can’t stay around long tonight, Maria. I don’t think they’re going to be away very long.” (p.61)

On the back we read that Morelli “has a story to tell that will hold you from the front page and tells it without pulling any punches.”

With a small red circle added to the front cover with “35c” on it, it was also made available in the States.

Duke Linton, Kill and Desire (1950)

A novel about enduring, giving, and receiving pain.

In the opening stretch a terror-stricken anonymous man is on the run from killers, exhausted, bruised from falls, lacerated by the broken glass on top of a wall, wounded, gangrenous, and dying just as he reaches the cabin of a man he was evidently trying to get to.

In the second stretch, a rich girl whose car has smashed at night into the back of a car crawling along a country road has to keep up with its silent, swiftly striding owner who won’t spare her a moment of civility or compassion as she limps along or show any interest in her even when they spend the night together. In the third, sounding a bit like a D.H. Lawrence character, she is alternately furious at and attracted by his indifference (he’s pagan-handsome when he strips for a swim) and gets him beaten up by a farmer’s lads after claiming assault. (He isn’t castrated, as had seemed likely.)

After that, a tall man in grey goes around Chicago torturing and killing the several gangsters who had been responsible for his brother’s suffering and death in the opening section. Finally, the girl locates him after he’s returned to his cabin in the woods, where he sounds like a different character, and things go horribly for her in an unexpected brief penultimate chapter.

According to Steve Holland’s introduction to the 1997 reprint, the book, in fact by Stephen Frances, was reissued in 1956 as Hounded, over the name of Darcy Glinto, and in 1964 as To Kill or Be Killed, by Munro Carson. There was no way in which it could have been a Glinto.

Hank Janson, Some Look Better Dead (1950)

The involvement of reporter Janson (character) with a genuinely sadistic man and his genuinely masochistic-dependent wife permits Janson (author) to release some of his darker inner energies, especially in the Grand-Guignolesque flashback account at one point of the jealous husband imprisoning the naked wife for six months in a specially prepared dark closet two feet by three, which seems highly unlikely. So far as I can tell, pain was Frances’ querencia, the area in which he was emotionally most at home.

Gene Ross, Lady, Throw Me a Curve (1950) (in America, Curves Cause Trouble, 1953) NEW

Private-eye Saun O’Malley—not hard-drinking, violent, wise-cracking, or priapic— is hired to clear the name of a blue-blood called Michael Christie accused of killing a night-club owner called Raymond Valda, which you know, with names like that, he couldn’t have done. A perfectly competent and unexciting sub-Chandleresque first-person narrative which I’d probably have thought was by an American if I hadn’t learned otherwise.

Danny Spade, The Dame Plays Rough (1950; A la casserole!, 1952)

I’ve had to read this in French, in the prestigious Série Noire. It comes through as a perfectly competent, first-person, Gold Medalish narrative of a New York private-eye (called Danny Spade), who lets a sexy blonde pick him up at the outset for a “simple” meeting with someone that results in his being knocked out and waking up beside a murdered man, which sends him hunting to clear himself, with the usual ingredients—other women, a crooked doctor, a night-club act, a beating to extract information from him, a cab-chase through Manhattan, a reconciliation with the Law, etc. Not erotic, not particularly violent. I see that five other novels by Spade are listed in the BLIC.

Danny Spade was one of the few female writers from the time to tackle the “gangster” genre, professionally known as Dail Ambler but born Betty Williams.—SH

Ross Angel, Tomorrow—the Chair (1950) NEW

Narrator Keet Hennessy is going to the chair next morning. Retrospection time.

Stash Jenkins and his smalltime New Yor gang—Stash, Art Graun, Shove Kennedy, Keet—stick up the Montega Club, movie style. Keet shoots Shove when he turns yellow.

Keet goes down to Cornelia Street in the Village to visit with lovely Maori Huia Lodge, GI bride, only to find that she’s just shot her abusive husband. They take it on the lam, sort of like in Gun Crazy, robbing a couple of service stations, with killings, and holing up in Cincinnatti.

Keet is taken on as bouncer at the disreputable Nat’s Niterie. Intervening when local bigshot Fingers Miller’s hoods are beating up a woman, he causes the death of one of them, and is taken away and severely beaten himself. While he’s convalescing elsewhere, Huia goes off and returns with needed cash after a stick-up, but has been raped by two of Fingers’ guys. Keet returns to Cincinnatti without telling her, shoots one hood between the eyes, the other in knee and belly, douses Fingers’ pajama jacket in gasoline, and turns him out of the car, bottomless and jacket aflame, before news photographers whom he’s alerted.

In Amarillo, fat lawyer Abe Galloway hires Keet to bump off his partner Hope. Keet hires PI Schenk to find out Galloway’s routines, tells Hope about the plot, has Galloway caught in flagrante robbing the safe, and takes off with some of the contents himself, after leaving Galloway and Schenk dead and Hope unconscious.

He and Huia cross into Mexico, with help from smalltime crooks Pedro Gonzales and Miguel, and are having a good time when Art Graun, from Stash’s gang, turns up with an interesting tale. He and Stash had come upon a wrecked car on the highway with dead rich kids in it, and lots of jewelry, which Stash buried. But Art doesn’t know where, and Stash is now in jail in Knoxville.

With the help of forged documents provided by crooked printer Edward Mather, they crush Stash out of jail, but during the ensuing shootout have to leave Huia behind. In Memphis, lowlife floozie Lyn tries to stick them up for the reward, but instead of bumping her off they take her on as an accomplice. Keet kills a service station attendant and sleeps with Lyn, drunkenly.

Leaving her, he’s hijacked and badly beaten on the highway, but millionaire cattle queen Carole Blaire happens by and has him nursed back to health, and other things, at her ranch. Returning to Memphis, he learns that Hauia is there, and is reuniting with her when Lyn intrudes, armed with a bottle of vitriol, and Huia is shot dead. Keet goes after Lyn. “The Border Patrol was about a minute too late. When they got to me I was quietly and methodically stamping her face into pulp.” (128)

Some more quotations. The first is from when he and Huia are dealing with a couple of service-station attendants during their first stick-up.

“Let her have it,” I shouted to Huia, but she didn’t have the nerve. I belted after the dame as hard as I could and caught her about fifty yards down the road. I grabbed the loose fold of her coverall and grabbed her back to meet the wrench. It was a pity, she was a nice looking dame. Huia was having hysterics on the back seat where she had hidden herself. I grabbed the dough in the till and jumped for the driving seat. We got away just in time. As I shot out onto the highway two or three of the local citizens were running towards us. As the headlights picked them up I saw one man go down on his knees, throwing up a nasty looking twelve bore. I swung the wheel hard over and the buckshot tore a lump out of the roof. Then I swung back, grazing one of the men who leapt for the ditch with a yell. The guy with the shotgun wasn’t so lucky he had to get up off his knees. I caught him fair and square as he bolted for cover. He won’t fire any more shotguns for a long time, if at all. (24)

Here he is with Carole Blaine.

On the way to El Paso I asked her about herself. She told me she was the daughter of an upstate cattle rancher.

“It shoulda been a horse,” I said.

“What horse?”

“The rescue. You should have swept me up into your saddle and galloped away …”

“You’re getting things a little mixed, aren’t you? That’s what sheiks are supposed to do with young ladies they want for their hareem.”

“College girl, huh?” I said sourly. “Maybe it would work in reverse anyway. You never know till you try.”