Found Pages: The Remarkable Harold Ernest (“Darcy Glinto”) Kelly, 1899–1969.

Violence, Inc: Part 2, 1929–1939

- Part 1. 1899 to 1928

- Part 2. 1929 to 1939

- Part 3. 1940 to 1945

- Part 4. 1946 to 1955

- Part 5. 1956 to 1975

For the Introduction to Violence, Inc., click here.

1929–1939

The 1899–1928 works that I’ve mentioned are not, by and large, about violences perpetrated by professional criminals, or presented from the criminal’s point of view. Things are different in the 1929–39 period.

Presumably the book-buying classes no longer feel that whatever the incidental cost in eggs, the system works well enough and the omelets are tasty.

The doings of Germany’s National Socialists show that a government can itself be gangsterish.

Here, for what it’s worth, is Jean-Paul Sartre on the decade. The “we” here are French intellectuals of his generation.

From 1930 on, the world depression, the coming of Nazism, and the events in China opened our eyes. … The first years of the great world Peace suddenly had to be regarded as the years between wars. Each sign of promise which we had greeted had to be seen as a threat. Each day we had lived revealed its true face; we had abandoned ourselves to it trustingly and it was leading us to a new war with secret rapidity, with a rigour hidden beneath its nonchalant air.

“What Is Literature?” and Other Essays (1988), p. 175In 1939, James Hadley Chase’s No Orchids for Miss Blandish essentializes a decade and becomes a bestseller.

Note: The order of the following items within each year is normally fiction (British, American, other), non-fiction, movies, and, in boxes, events.

1929

Richard Hughes, A High Wind in Jamaica.

One of the best British novels of the inter-war years, brilliantly entering into the strange but recognizable minds of supposedly “innocent” children (here a mid-Victorian group aboard an anachronistic pirate ship). Their patterns of concern are very different from those projected on them by their parents, with small things bulking large and large things, including death, only shadowy, like that of brother John, falling from a height.

Thirteen-year-old Margaret, small for her age, is made the sex-toy of the eccentric but likable captain and mate. Ten-and-a-half-year-old Emily mortally slashes a bound and helpless man who scares her and subsequently, as memories fade and adults impose their version of the children’s experiences, allows the captain and others to hang for it.

As her father watches her asleep in her bedroom before the trial,

his sensitive eyes communicated to him an emotion which was not pity and was not delight: he realized, with a sudden painful shock, that he was afraid of her.

But surely it was some trick of the candle-light, or of her indisposition, that gave her face momentarily that inhuman, stony, basilisk look? (Ch.10)

In 1938 Hughes will publish In Hazard, an impressive reworking of the central situation in Conrad’s wartime “Typhoon.”

Later, writing painfully slowly, he will produce The Fox in the Attic (1961) and The Wooden Shepherdess (1973), in which Germans in the 1920s and early Thirties, including Adolf Hitler, are rendered from the inside with extraordinary plausibility.

He understands both exterior and interior tempests and the blurring or dissolution of conventional categories.

John G. Brandon, Gang War, in The Thriller, vol 1, no. 46, Dec. 21,

I include this only for the gap between English (fictive) gangs and American. The work appears in that long-lived weekly The Thriller, large pages, triple columns, tiny print, the only touch of colour the red on the front cover.

For details, see Note 45.

W.R. Burnett, Little Caesar

The gangland rise and fall of a socially inept and much less politically skillful Capone, Rico Bandetti, whom Burnett called “a gutter Macbeth.” According to Steve Holland it was “a perennial favourite” in England, “boosted by the regular appearance of Jimmy Cagney and Edward G. Robinson in cinemas.” (THJ, 72).

Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest

The nameless short, fat Continental Op, hired to clean up the Western copper mining town of Personville, sets gangster against gangster in the ultimate gunfire-and-gang-war novel.

We waited a moment, and then Pete the Finn appeared in the dynamited doorway, his hands holding the top of his bald head. In the glare from the burning next-door house we could see that his face was cut, his clothes almost all torn off.

Stepping over wreckage, the bootlegger came slowly down the steps to the sidewalk.

Reno called him a lousy fish-eater and shot him four times in face and belly.

Pete went down. A man behind me laughed.

Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars are descendants, as is Walter Hill’s Last Man Standing.

Jonathan Latimer wrote the screenplay for an unmade filming of it.

Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front, first translation into English

An anti-militarism classic.

Unfortunately, the 1914–18 butchery whose nature, dimensions, and duration no-one, not even H.G.Wells, had foreseen, encouraged the belief in Britain that the only respectable alternative to militarism, if rational conflict-resolution failed, was pacifism, as voiced, for example, in the infamous 1933 debate of the clever young gentlemen at Oxford—a stance of less than zero utility when it came to dealing with the fascist adventurism in the Thirties.

Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel; from the Diary of a German Storm-Troop Officer on the Western Front (first English translation of the second edition.)

Actually I’ve been using Michael Hoffmann’s brilliant Penguin translation, with its refreshingly candid introduction.

No, this isn’t some kind of proto-Nazi celebration of blood and iron and glorious deaths. There are deaths a-plenty, and wounds, a number of them Jünger’s own, but they aren’t glorious, though not lingered morbidly over either. The book is very much about living.

Young Lieutenant Jünger is a noticer, whether of military or pacific doings. At times he’s scared, as he admits, but it passes. Death is always present, but not worth brooding about. The here-and-now gusto reminds me of the free-spirited energy that Richard Hughes’ young British protagonist in The Fox in the Attic is impressed by in the early Twenties when he stays with an aristocratic German family on their estate.

It’s very much an officer’s book, with a lot more attention to terrain and combat plans and the needs of his men than you normally get, and more individual freedom within a changing framework. There’s epicurean eating and drinking, times-out during the lulls (even, at one point a bit of sunbathing in a shell-hole), a more casual attitude towards enemy shells and mortars. You have a fair idea of where they may land and their range of serious damage.

He attacks boldly, but has discretion, seemingly, in assessing the odds in particular situations. There’s no sense of an impersonal machine stupidly grinding out death.

Depending on one’s mood, there can be almost too much “concreteness” here— nature notes, character sketches, clothing, decision-making, dodging along trenches, missiles hitting and missing, etc.. This isn’t like The Red Badge of Courage, building thematically through symbolic incidents. A lot of it is one thing, and another thing, and another.

But towards the end, with its memorable long battle episode, we indeed have what Hofmann calls

the Jünger repertoire, the contemplation, the casual fearlessness, the observation of huge and tiny things, the melancholy, the idea of the war-as-nature, the big metaphors, but with a new quality of introspection.… Influenza, enemy propaganda, bad food, silly accidents and foolish orders have all taken their toll …

As has, one might add, the recognition that Germany has lost the war.

But there’s no talk of stabs-in-the-back or next time.

Albert Londres, The Road to Buenos Ayres, English translation with an introduction by Theodore Dreiser.

A very Gauloises-and-aperitifs, man-of-the-world, journalistic account of exploring the White Slave Trade, here principally the organized flow of girls from Poland and France to Buenos Aires, which in Londres’ presentation (corroborated in Edward J. Bristow’s massively researched Prostitution and Prejudice, 1983) sounds like the world capital of prostitution in the 1920s. Lots of “verbatim” conversations with pimps and girls. A trade like any other, with pimps taking hungry poor girls and smartening them up so that they can proceed to earn good livings for themselves and their guardian angels. Entrapment? Violence? Mais non, only occasional black eyes for misbehaviour.

But some of the pimps come across as more unsavoury than the author seems to realize, and darker waters can be glimpsed from time to time in the casual trading of girls among pimps, the very uneven dividing up of their earnings, the problems for the occasional girl who does try to break away, and Jewish girls from desperately poor homes in Poland servicing sixty or seventy clients a day in order to have money to send back home.

Eight reprintings by 1938. Probably the book that put the words “Buenos Aires” indelibly on the erotic map.

The Wall Street stock-market crashes.

In the memorably titled St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Capone’s Chicago, seven members of Bugsy Moran’s gang are lined up facing a garage wall and shot by Capone’s men disguised as cops.

Attempting to curb further deadly incidents like the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, the mob leaders formed a national federation of underworld gangs. The result? Organized crime. The bosses agreed that they would peacefully settle disputes between their respective gangs while individual mobs could run their own territory any way they wanted.

Debra Pawlak, “Rumrunning and Hijacked Hooch—the Purple Way” (Web)In Hit ‘Em Hard: Jack Spot, King of the Underworld , Wensley Clarkson reports that, “By the end of the 1920s, there were 295 registered clubs within one mile of the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus,” plus at least fifteen unregistered ones near Leicester Square. Among the ones in Soho, whose streets at that time he calls “the wickedest in the nation”) were Kate Meyrick’s 45 Club, the Big Apple Club, the Twilight Club, the Hell Club, the Nest Club, the Shim-Sham Club.

By then, the five Sabini brothers, Darby, Joe, Charlie, Young, Harry, and Fred had migrated to Soho from Little Italy in the Clerkenwell Road and taken over the racecourse protection racket, “protecting” bookies (for a consideration) from having their operations wrecked. Gambling, legal and illegal, was a major industry. (Ch. 2)

1930

Edgar Wallace, On the Spot

A play about Capone-figure Tony Perelli. No less a critic than Q.D. Leavis calls it “nearer to art and survival than anything that is likely to be in Jack London’s fifty volumes, perhaps because [Wallace’s] lack of ideals, his shrewd newspaperman’s knowledge of character and his friendships in the criminal underworld qualified him to be the dramatist of this society.” (Scrutiny, VII, 1939, p. 479)

John Hunter, When the Gunmen Came

As a 317-pp. hardcover, this is a substantial read and, for me, a slow one. There is very little signposting to what is coming, and little in the way of what feel like genre conventions. American gangs, two of them, have set up shop in a recognizable London with lots of place names, and are primarily concerned with a massive theft of bullion from the Bank of England organized by master Chicago gangster Warbeck, a suave, literate, and ruthless figure with some factual overlaps with Al Capone.

The British police team is headed by handsome young Billy Carew of the Yard, who after a bit is given without any fuss those expanded police powers that are desiderated in Edgar Wallace’s When the Gangs Came to London two years later. A lot of cops are now armed with handguns.

The opening sentence is promising—“Sunshine flooded Piccadilly when Les Stanton was shot dead on the corner of Old Bond Street”—, with mystery woman Jenny Trent brought immediately into the action, who is trying to infiltrate the gang in order to get close to Warbeck but becomes a love interest for Carew. Other subplots or sub-narratives involve characters like super-fence Mose Kilinski, fence’s runner Danny Brill, Warbeck’s rival, crack racing-driver Sarn (which looks typographically like “Sam”), Italian-American gunman Pete Tetrano, and escaped American convict Oliver Trent.

The impact of the narrative is slightly muffled by Hunter’s bad ear for American criminal speech. At times he seems simply not to be trying. We are told, for example, that Tetrano speaks broken English, but he rarely does so in these pages. Nevertheless, there is a pervasive feeling of danger (even if no breath-stopping accounts of violence), an abundance of incident, and a plot that keeps pushing along with something of the gusto of a Fantomas serial. One can “see” through Hunter’s rather too mannerly prose to the events and emotions that he is describing.

If the American gangsters here have a salient feature distinguishing them from the domestic criminal fraternity, it is that they are GUNmen, with no compunction about killing and no remorse afterwards. They also seem a lot more accustomed to fast driving.

C.S.Forester, Plain Murder

When three young employees in a London advertising agency face the dreaded sack after a superior catches them out in a bit of chicanery, the large, energetic, and ambitious, ringleader kills him (shooting him in his garden from a distance on bonfire night), follows it up by disposing of the guilt-ridden weaker of his two co-conspirators, and, as he rises in the firm, turns his sights on his unsatisfactory wife and the other former conspirator. The slightly ironical tone would be appropriate to a narrative of the rise and fall of a American gangster.

Standing in the railway carriage [Morris] constituted what a catholic mtaste might term a fine figure of a man—big and burly in his big overcoat, with plenty of colour in his dark, rather fleshy cheeks. His large nose was a little hooked; his thick lips were red and mobile; his dark eyes were intelligent but sly. The force of his personality was indubitable, he was clearly a man of energy and courage.

But this is Depression England, the land of narrow opportunities, and his luck runs out, though not because of any action on the part of the authorities. A curious book, not quite “English” in the decisive violence of its (Jewish?) protagonist and the ineffectiveness of the police.

No wonder the British young were interested in high-energy American gangsters like Capone. No wonder Forester himself, who had done a Golden Age “English” murder in Payment Deferred (1926), preferred the larger-scale lethal activities of a Hornblower.

Armitage Trail (Maurice Coons), Scarface

The novel that Ben Hecht adapted almost out of recognition for the movie of that name. A largely sympathetic tracing of the career of a figure with a lot in common with the one described in Robert J. Schoenberg’s Mr Capone (1992)—violent at times, but essentially an organizer in a business with violent competitors.The speech patterns seem a bit too formal, but the narrative prose isn’t doom-laden mannered. There is mention of the fact that individuals being taken for a ride might be tortured before being killed.

Erskine Caldwell, Poor Fool

In the uniquely horrific, hallucinatory second section of this brief novel, slow-witted pug Blondy Niles, who’s just made a rigged comeback, is psychologically trapped in an abortion mill operated with total callousness by huge Mrs. Boxx, where he does the housework, mops up the blood after operations, carries dead and pitifully dying victims down to the basement to make room for new ones, and shares Mrs. Boxx’s bed at night with the effete Jackie.

Mrs. Boxx’s garrulous husband, who was castrated in North Carolina after raping a farm girl, tells Blondy of the underground city where the dead from all ages carry on their social and sexual lives, and warns him that Mrs. Boxx and Jackie intend to castrate him. Which they will have no trouble doing, since he is as powerless to resist Mrs. Boxx as a bird hyponitized by a snake.

The book first appeared in a luxury limited edition with erotic illustrations. It could only have been American. You could not have had either the cruelty, the insatiable greed, the blatant operation of the lethal abortion mill, or the moral affectlessness on Blondy’s part (he’s made only mildly uncomfortable by the sufferings of the victims of botched operations), in a British novel from this time.

Lt.-Commander and Mrs. H.L. Haslewood, Child Slavery in Hong Kong; the Mui Tsai System

A brief lucid book by the husband and wife who had been responsible for bringing the Mui Tsai child-slavery system in British-administered Hong Kong to public attention in the early Twenties (see 1920 above). Carefully details the questions asked and promises made in Parliament, reproduces official communications to and from Hong Kong, and analyzes how in fact the laws have simply not been administered, British Governors obviously not wanting to tangle with rich and powerful Chinese or risk being accused of violating traditional cultural practices. By the end of the book new laws against this literal slavery have passed, but to what effect remains to be seen.

The following is the nearest thing to a report of atrocities in the book, but it’s enough:

Below the hotel in which we lived there was a house owned by Chinese who had a number of these unpaid girl slaves, among them being a small child of about eight years old. One evening we were on the balcony overlooking this house when we heard the most terrible screams from this child in which pain and terror were dominant. I had heard her crying and moaning on a former evening, but these sounds were different. They were cries of absolute terror. The owner of the hotel informed us that he and his wife had heard similar sounds, “as of someone in agony,” coming from this house. (pp.13-14)

Little Caesar, Mervyn LeRoy

Edward G. Robinson as Rico, assisted initially by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., rises in the rackets and dies yellow in a hail of lead.

L’Age d’Or, Luis Bunuel

Gets over fifty references in the index to Ado Kyrou’s Le Surréalisme au Cinéma (1963) and a seven-page eulogy. The intermittent gasping embracings (clothed) of Gaston Modot and Lya Lys still carry an erotic charge. But the opening segment on the Med feels like home movies, with Max Ernst and others dressed perfunctorily as “bandits” (or is it “pirates”?) violating Bunuel’s own later cardinal rule that to produce surrealist effects in the cinema you show normal-seeming people behaving oddly.

But at the time there was right-wing vandalism during the screening at Studio 28 on the Left Bank, and a newspaper campaign against it, and one can see why back then, and during its ensuing years of virtual invisibility, it should have figured as a major anti-clerical, anti-bourgeois-decorum work of Surrealist provocation.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs is established.

How many murders, suicides, robberies, criminal assaults, holdups, burglaries and deeds of maniacal insanity [marijuana] causes each year, especially among the young, can only be conjectured.

Harry Anslinger, Commissioner 1930-1962 (undated comment)If there were a category of Law Criminals, Anslinger would deserve to be high up on the Public Enemy list.

Gang war begins in New York and rages for fourteen months.

The trial of Peter Kürten (1883-1932), the so-called Vampire of Dusseldorf, takes place. According to one website, he is “convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of nine women and children, and the attempted murder of seven others. It is certain, however, that the number of his victims far exceeded that total.” According to another,

In the entire history of crime no one killer has caused such widespread fear and indignation as that created by Peter Kürten in Düsseldorf in the inter-war period. It may be said—and without exaggeration—that the epidemic of sexual outrages and murders occurring between February and November 1929 provoked a wave of sheer horror and contempt not only in Germany, but throughout the entire world. (Alexander Gilbert)

Frits Lang’s M is loosely based on it.

In Second Manifesto of Surrealism, André Breton writes:

One can see why Surrealism was not afraid to make for itself a tenet of total revolt, complete insubordination, of sabotage according to rule, and why it still expects nothing save from violence. The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd. Anyone who has not at least once in his life dreamed of thus putting an end to the petty system of debasement and cretinization in effect has a well-defined place in that crowd, with his belly at barrel level.

1931

Edgar Wallace, On the Spot; Violence and Murder in Chicago (novel).

A masterly expansion of his play, in which the novelistic parts are obviously providing information that was in Wallace’s mind while he was writing the play. A three-dimensional presentation, with the past frequently entering in, of the complicated interactions of sentimental, charming, vain, ruthless Capone-figure Tony Perelli and a variety of other gangsters, women, and cops. The actual Capone, or at least the Capone of Robert J. Schoenberg’s Mr.Capone (1992), was less wicked.

For quotations, see Sidebar 6.

Dashiell Hammett, The Glass Key

The dynamics of civic corruption observed non-judgmentally by gentleman-gambler Ned Beaumont, best friend of city boss Paul Madvig. Payback time comes for the best-known beating (of Beaumont) in crime fiction.

O’Rory’s face was liver-colored. His eyes stood far out, blind. His tongue came out blue between bluish lips. His slender body writhed. One of his hands began to beat the wall behind him, mechanically, without force.

Grinning at Ned Beaumont, not looking at the man whose throat he held, Jeff spread his legs a little wider and arched his back. O’Rory’s hand stopped beating the wall. There was a muffled crack, then, almost immediately, a sharper one. O’Rory did not writhe now. He sagged in Jeff’s hands.(Ch.9, iii)

William Faulkner, Sanctuary

Small, white-faced, chinless, automatic-carrying, psychopathic, sexually impotent bootlegger Popeye Vitelli rapes fast-living seventeen-year-old college-girl Temple Drake (a judge’s daughter) with a corncob after a car accident has deposited her among bootleggers, and hands her over to Memphis whorehouse madam Riba Rivers for safe-keeping, where she has hot sex (“nekkid as two snakes”) with nightclub bouncer Alabama Red as Popeye stands drooling at the foot of the bed. After being “rescued,” Temple perjures herself at a trial that results in the lynching of an innocent white bootlegger.

A reviewer called it “a sadistic story of horror—probably the most sickening novel ever written in this country” and said it had had “quite a large sale.” Contains two of the most horrific sentences in serious fiction:

“Only we never used a cob. We made him wish we had used a cob.”

Octave Mirbeau, The Torture Garden, first English translation of Le Jarden des Supplices (1899)

In an AbeBooks blurb it is described as:

Following the twin trails of desire and depravity to a shocking sadistic paradise: a garden in China where torture is practiced as an art form. A dissolute Frenchman discovers the true depths of degradation, infinitely beyond his prior bourgeois imaginings. Entranced by a resolute English woman whose capacity for debauchery knows no bounds, he capitulates to her every whim amid an ecstatic yet tormenting incursion of visions, scents, caresses, pleasures, horrors, and fantastic atrocities. Well ahead of its time, The Torture Garden is exceptional for its detailed descriptions of sexual euphoria and exquisite torture; its political critique of government corruption and bureaucracy; and its revolutionary portrait of a woman, which challenges even contemporary role models of feminine autonomy.

City Mid-Week: the Newsmagazine of Business Life, no. 1, December 9

Harold Kelly and a fellow journalist (unnamed and working for Reuter’s—John Ramage Jarvie?) are co-founders.

It’s a 20-page weekly, approximately 12” x 9”. The first issue reads for the most part as if it were the newspaper of a small city, with lots of ads (particularly for men’s and women’s tailors), local news and notes, advice for women, reviews of amateur theatricals, music recitals, sporting events, “philosophical” columns, and so forth.

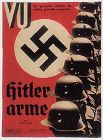

However, the principal article on the front page is “Hitler and the London Banks: Envoy’s Private Meetings,” about a visit to London by Alfred Rosenberg, described here as Hitler’s chief lieutenant, and opening:

At the moment, German politics are British politics. The movements of Herr Adolf Hitler, the German nationalist leader, are of more importance to this country than the tariff policy of our own National Government.

As the anonymous writer points out,

If Hitler attains power he will default on reparations [to France]. He will not default on commercial debts.

For this reason, British finance is looking with a kindly, and even a hopeful eye, on Adolf.

The unsigned front-page article of the final issue names names about politicians and other public figures (British) with links to the armaments industry. It concludes with:

Until the principle of war as the final means of arbitration becomes obsolete the necessity for the manufacture of arms will remain, but at a time when there is a world-wide plea for a reduction of armaments and an attempt to bring about a lasting peace it is a strange anomaly that those who are likely to gain most by outbreaks of war appear to have opportunities of influencing the policy of the nations which are unequalled by those afforded to any other form of industry.

For more about the paper, see Sidebar 10 and Supplementary.

John Swain, The Pleasures of the Torture Chamber

An unscholarly grab-bag of horrors without any obvious point, though there seems to be some anti-Catholic bias (the Inquisition, the wars of religion, etc) and an anxiety about the resumption of torture.

Too much of the book is in the form of brief descriptions that numb the mind and sensibility. But a long quotation from Harrison Ainsworth’s novel The Tower of London (1840) demonstrates what horrors were deemed acceptable later in “educational” reading.

Emmanuel H. Lavine, The Third Degree; a detailed and appalling exposé of police brutality British publication of 1930 American edition.

An experienced crime reporter describes appalling violences inflicted on criminals who appear at times to have phenomenally high pain-thresholds, and discusses the workings of police corruption, political patronage and the sanctions for cops who offend politicians or violate the police code of omerta.

During the interrogation of some alleged kidnappers in an attempt to save a kidnaped boy’s life,

I covered Bellevue Hospital for many years and saw hundreds of victims of gang beatings and accidents, but never saw such physical wrecks. Their faces seemed swollen to at least twice the normal size and were completely out of alignment. It was virtually impossible to distinguish their features. Where the eyes belonged there were little discolored slits running off at some peculiar angle.

An inch [?] of blood covered the floors, walls and desks in the different rooms. Broken blackjacks, rubber hose and the parts of four broken chairs were scattered in the mess. The men ruined their clothes and looked more like workmen employed in an abattoir than detectives. (ch. X)

We also (cf. the third-degreeing in No Orchids for Miss Blandish) have the interrogation of a powerful youth during which at one point

the detective pulled out his blackjack and struck Rumore across the Adam’s apple with all his strength. I thought the lad would have an apoplectic fit. He shuddered and shook, and his body writhed against the ropes that bound him, not in an endeavor to escape, but in an attempt to get his breath. Blood spurted half way across the room.(ch. VII).

America!

Public Enemy, William Wyler

Tom Powers (James Cagney) makes his way up in the bootlegging business, only to be caught off guard by a well-placed machine gunner, snatched by rivals from the hospital where he is recovering, and delivered to his home as a mummy-like package in a final shot from which we can infer that his death was not an easy one.

A fine pre-Code movie, with a rich variety of sharply-observed social types (where did all those bit-players come from?), and so much going on inside each frame that little camera movement is necessary (no montage at all, I think), and Cagney at his best as an emotionally insecure, at times appealingly boyish, but explosively dangerous roughneck.

Frankenstein, James Whale

A boundary is breached when the Monster drowns a little girl. Dwight Frye’s Fritz provides some unabashed cruelty. The Monster intrudes into the bride-to-be’s bedroom. We have entered zones of the unprecedented, the dangerous. The Baron’s “creature” has a will of its/his own.

Four years later The Bride of Frankenstein is Code-governed and the Monster loveable rather than marvelously strange and private. Whale’s contempt for the square citizenry stands out in the screeching, would-be-humorous over-acting he permits to Una O’Connor. The Middle-Europeans are now pure Hollywood and Count Zaroff a manikin in a jar.

Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera), G.W. Pabst.

Pabst brilliantly films the Brecht-Weill opera from the point of view of Mackie Messer (Mack the Knife) and his cheerfully larcenous and efficient gang in late-Victorian London, at odds with the odious fence Peachum, but hand-in-glove (hands-in-pockets) with Chief of Scotland Yard “Tiger” Brown.

M, Fritz Lang

A homicidal pedophile, his compulsions brilliantly conveyed by Peter Lorre, is hunted by police and “normal” criminals, the latter with their own organization and kangaroo-court justice system.

Al Capone is sentenced to ten years in a federal prison for income-tax evasion, winding up in Alcatraz.

Nine Black youths are found guilty in Scottsboro, Alabama, of raping two girls in a box-car. Widespread protests and new trials during the next several years. Eventually four were released and five served long prison sentences.

The International Labor Defense’s (ILD) involvement in the Scottsboro case, more than any other event, crystallized black support for the radical political movements, especially the Communist Party, in the 1930s. Accused of raping two white women (Ruby Bates and Victoria Price) on a freight train near Paint Rock, Alabama, nine young black men (Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Clarence Norris, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Haywood Patterson, Andy and Roy Wright, Eugene Williams), ages thirteen to twenty-one, were arrested on March 25, 1931, tried without adequate counsel, and hastily convicted on the basis of shallow evidence. All but Roy Wright were sentenced to death.

(Robin D.G. Kelley on the Web)“Stalin has delivered the goods to an extent that seemed impossible ten years ago. Jesus Christ has come down to earth. He is no longer an idol. People are gaining some sort of idea of what would happen if He lived now.”

(Bernard Shaw, The Rationalization of Russia, q. Niall Ferguson, pp.198-199)Japan invades Manchuria. The League of Nations imposes toothless sanctions. Japan withdraws from the League. See, for example, www.historylearningsite.co.uk/manchuria.htm

Nevada legalizes gambling.

1932

Edgar Wallace, When the Gangs Came to London

A precursor of McQ (with John Wayne, 1974) and its British TV follow-up series, Dempsey and Makepeace. Of no interest stylistically, and with no gripping moments, but of some interest thematically.

An American cop, Captain Jiggs Allerman, comes to England to help cope with the activities of an American gang, and is impatient with British police methods He says things like, “That’s the kind you don’t know in England—killers without mercy, without pity, without anything human to ’em.” (p.19) and “When the shooting starts, it’ll start good and plenty, and all the theories about this sort of thing not being done in England will go skyward.” (p.25). To which a British chief constable predictably retorts, “American methods are all very well in their way, but you can’t expect American police officers to understand the routine of work in London.” (p.107)

At one point, Allerman breaks down a hoodlum with ten minutes of private third-degreeing (undescribed) (p.141), demanding of the police chief, afterwards, “Are you putting the tender feelings of this man before the lives of your friends and fellow citizens?” (p.142). Later he recommends—unsuccessfully—having the two masterminds of the gang shot while trying to escape. “You’re not going to beat these birds by any gentlemanly methods.” (p.242).

When asked for his advice by the Home Secretary, he replies:

“Any suggestion I make, gentlemen, will sound immodest. The first is that I be given absolute control of the metropolitan police force for a month. The second is that you suspend all your laws which protect criminals. These fair-play methods of yours are going to get you in worse than you’re in already. I suggest you scrap every rule you’ve laid down for Scotland Yard, that you suspend the Habeas Corpus Act, and give us an indemnity in advance for any illegal act—that is to say, for any act that is against your law—that may be committed in the course of that month.” (pp.244; my thanks to Benoit Tadié for bringing this to my attention).:

But basically, though tommy-guns blast and pineapples explode at a few points, the book, as the blurb points out, is “Not a gang story but a detective mystery…,” an extrapolation from the pattern of Wallace’s The Four Just Men (1905), in which designated target figures are murdered despite police protection.

The mysterious gang of over two hundred members, big enough, as Allerman suggests, to have a representative on every floor of the big hotels, is more like an invisible Dr.Mabuse-like conspiracy than an American gang dealing in prohibited substances and activities (booze, gambling, “white-slavery,” etc). We see only a tiny handful of its members, and have no idea of its social organization, where the members live, how they pass the time when not criminalizing, what womenfolk they have, and so forth. Everything is told from the point of view of its targets and adversaries—the Establishment, one might say.

Also, despite the official recoil from “American” methods, the British lion isn’t wholly toothless. As Allerman reflects at one point, “The British were a peculiarly savage people in moments of crisis, and, if not savage, they were certainly ruthless.” (p.173). The new legislation that is passed mandates

Death for bombing, life imprisonment for being in possession of bombs, twenty-five lashes with the cat-o’-nine-tails for being in possession of loaded firearms, seven years and twenty-five lashes for conspiracy to extort money.” (p.185).

I seem to recall that a point was made of the addition of the cat to some sentences for robbery with violence in the 1930s. In any event, British “decency” stopped at the gates of penal hells like Dartmoor, as recalled in the memoirs of professional criminals. One of them explains that an advantage to opting for the cat in prison for the infraction of rules, rather than solitary confinement on bread and water, was that it wasn’t accompanied by further sanctions. One of the memorialists reports that the cat was less painful than the birch.

The problem of how to deal with violent men who themselves didn’t observe the rules of fair play would continue with respect to “American” methods, particularly the Third Degree.

John G. Brandon, The Dragnet, in The Thriller, no. 188, vol 7, Sept. 10, 1932.

For details see Note 51.

Robert E. Burns, I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!

A famous autobiographical account of Hell by a Northerner who in the early Twenties had helped rob a store of the equivalent of a hundred or so of today’s dollars and was sentenced to ten years in the Georgia chain-gang gulag with its back-and-spirit-breaking manual labour, rock-bottom amenities, agonizing punishments, pitiless guards, and merciless parole boards.

The author escapes, enjoys seven years of good-citizenry in Chicago, allows himself to be talked into returning to Georgia in the expectation of perfunctory re-imprisonment leading to pardon or parole, only to be double-crossed and thrown back into Hell again, from which he escapes a second time, making his way back North to survive in the shadows (the hellhounds of Georgia still on his trail), plus considerable publishing notoriety and sales.

For more about the book, see Sidebar 4.

William Faulkner, Light in August

In the principal plot, Joe Christmas, a Black who’s passing, has an intensely erotic relationship with genteel menopausal Joanna Burden, after whose murder he is shot and castrated (emasculated?) by a straight-arrow National Guardsman called Percy Grimm.

Scarface, Howard Hawks

Hawks responds to the success of Public Enemy as later he will respond to Casablanca with To Have and Have Not and High Noon with Rio Bravo. The machine gun at the end of Wellman’s movie was a tripod-mounted Vickers. Scarface is the first and ultimate Tommy-gun movie, with Tony Camonte blasting his window-shattering way to power in a pre-Code movie rich in characters whose names end in vowels and with hints of an incestuous sister-fixation. Much more intense and concentrated than the novel, and much cruder in its treatment of its hero-villain.

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, Mervyn LeRoy.

An admirable demonstration of the virtues of pre-Code Hollywood.

Clothes have a well-worn look. The principal younger women are faintly pretty and not bothered by unmarried sexual relationships. The convicts are neither macho nor cutely buddy-buddy with the new fish. The guards are credibly brutal without being shown constantly inflicting pain (after some early punching and kicking and an effective off-screen strapping).

Muni doesn’t repeat his Scarface over-acting, and developments in his character are conveyed in forward jumps from one time-spot to another that don’t need explaining.

The members of the parole board feel credible, as do the prosecutor arguing against Muni’s release. So does the silver-tongued gentlemanly representative of the unnamed Southern state assuring Burns and his well-wishers in Illinois that if he returns, there will simply be three months of painlessly pro-forma re-imprisonment before he receives a pardon; and an inconclusive ending.

Since Burns himself was advising during the filming, we get valuable fillings-in of the look and feel of things while the convicts are sleeping (chained), eating, working, and occasionally relaxing.

The Most Dangerous Game (in Britain The Hounds of Zaroff), Ernest B. Schoedsack and Irving Pichel.

The thrill of the hunt and the kill, followed by (in intention) the ecstacy of rape on Count Zaroff’s South Seas island. But this is not an invitation to sadistic fantasies by the male viewer. Fay Wray’s vulnerability is an extension of Joel McRae’s, and we urgently want them both to escape from Leslie Banks’ suavely crazy Cossack count—two wholesome, brave North Americans, in contrast to the drunken all-American boor played by Robert Armstrong, who pays horribly for his social sins.

A French critic (Michel Caen in Midi-Minuit Fantastique?) praised the Count as a Sadean figure who plays his deadly game rigorously, or was it scrupulously? What movie had he seen? Zaroff’s human prey are sent out, armed only with a large knife, into a terrain about which they know nothing. Zaroff, who knows it perfectly, comes after them with projectile weapons. When Rainsford (McCrea) makes things a bit difficult for him, he replaces his bow with a high-powered rifle and calls for his pack of hounds. When Rainsford survives past the deadline that he’s given him, he tries to kill him anyway.

A glimpse of a coastline stretching away as far as the eye can see makes nonsense of the talk about the island’s smallness. The fragile bridge that Rainsford constructs across a chasm would have been immediately visible as a fake. The so-called infallible trap of the falling tree depends on someone actually treading on the vine across the path. The Island of Lost Souls is a better movie as a whole. But The Most Dangerous Game is still a classic, with Leslie Banks and Joel McCrea beautifully antithetical as two types of hunter, and Fay Wray a spunky heroine.

An exemplary sufficiency of glimpses, when what is shown feels real—the stokehold crew panicked and screaming as steam and inrushing sea ravage them; a shark speeding underwater with deadly impersonal grace before the skipper goes under; a rotting head in a bottle in Zaroff’s trophy room. Shock-effect unfairness (in movie terms)—the opening group on the yacht, whose arguings and joshings we’ve been drawn into, suddenly all snatched away. Hinted-at horrors—the sinister tongueless servant’s skill as a torturer. The hunting horn. The baying of hounds.

Above all, the incomparable Zaroff of Leslie Banks, perfect in accent and body English, segueing in the pre-hunt part between good-host attentiveness, aristocratic annoyance, erotic gallantry, hunter-to-hunter camaraderie, deadly intent momently revealed, and insane pseudo-reasonableness about his own “fairness.” Hurrying after the hounds, his whole body quivers bowstring-taut with lust for the kill.

Sarban’s 1952 novel The Sound of His Horn is an interesting spin-off from it, set in a quasi-feudal estate some time after the Nazis won the war, whose master enjoys the power of life and death—and hunting human prey with surgically altered human hounds.

The Island of Lost Souls, Earl C. Kenton

Dr. Moreau on his South Seas island, marvelously incarnated by Charles Laughton, plans an interesting mating experiment for reluctant guest Edward Parker’s fiancée and one of the larger beast-men, but ends up screaming on the operating table in the House of Pain.

Freaks, Tod Browning

A powerful and unique movie employing actual side-show freaks, and concluding with a horrific bit of (unseen) Grand Guignol action. My own guess is that the outrage the movie created was because it showed the “freaks” as three-dimensional human beings feeling normal sexual desires. What, the inflamed and disowned imagination demands, is going on in the nuptial bed after one of the two Siamese-twinned girls gets married?

The Mask of Fu-Manchu, Charles Brabin

A miraculous pre-Code offering from later oh-so-All-American-wholesome MGM. As if an exiled-in-Hollywood decadent poet had been commissioned to throw in as many power-effects as possible from other horror movies and exceed them in outrageousness.

So we have mummy-wrapped figures emerging from British Museum sarcophagi to kidnap archaeologist Sir Lionel Barton, a descent into a desert tomb, a graveyard digging at night, an extended session on the operating-table, a dance of bolts of electricity between two poles, an opium den, a Central-European-type covered cart, an impending virgin sacrifice, a death-ray gun flooring men like a fire-hose.

Plus (here we go) enough fiendish torments to bear out Nayland Smith’s comment, apropos of the unfortunate Sir Lionel, that “They have ways in the East of shattering the strongest courage”— the torture of the reverberating bell (from Octave Mirbeau’s The Torture Garden?) from which Sir Lionel isn’t rescued (but daughter Sheila gets his hand back), a pair of screens with long sharp spikes closing in towards another savant fastened on a stool, a cantilevered beam inexorably lowering Lewis Stone’s Nayland Smith into a pit of crocodiles, and a whipping by two loin-clothed Nubians of suspended bare-to-the-waist Terrence, fiancé of virgin Sheila, under the command of erotic-sadistic dope-smoking Myrna Loy (“Faster! Faster!”), who intends to have him for herself and dispose of him, interestingly no doubt, when sated.

All this as the creation of Karloff’s magnificent Doctor Fu-Manchu (doctorates from three American universities), relishing the sufferings, actual and to be, of his captives, lusting after the excavated golden mask and scimitar of Ghengis Khan that will ensure him world mastery, and full-throatedly exhorting the assembly of Mongol chieftans in his palace hall, “Conquer and breed. Kill the white man and take his women.”

Compared with all this, in its spectacular Chinese-type decor, the group of American captives are a pretty pallid and helpless bunch, and screechily over-acting dishwater-blonde Sheila simply doesn’t have it in competition with Myrna’s marvellous Tah Lo See. According to the American commentator on the now re-released uncut copy, who predictably (in contrast to the Surrealists) views the whole thing as a camp caper, an incentive for the movie was William Randolph Hearst’s felt need to awaken us to the Yellow Peril. But obviously that wasn’t what was in the minds of the three delirious script-writers. It’s little more than last-minute luck, rather than the moral and intellectual superiority of the West, that leaves the crocs unfed, the spikes unbloodied, and the virgin un-immolated.

The super-villains of the Bond movies are all the more a schoolboy silliness beside this sexually sophisticated cultural subversion. No wonder The Mask of Fu Manchu had multiple censorship problems and vanished for a good many years. The sanitized version re-released by the studio some years ago on tape or disk is pretty dull.

Night after Night, Archie Mayo.

A sign of the pre-Code times, with Mae West in a small part. Gangster George Raft, elegant in a nouveau way, runs the biggest classiest speakeasy in town in the former family mansion of socialite Constance Cummings, who visits it to wander down memory lane during the days before she’s due to marry for money a man she doesn’t love.

Raft is smitten, dinner-dates her (along with the middle-aged academic from whom he’s trying to acquire a touch of verbal class), mistakes a sociable peck on the cheek for love, goes to her Park Avenue house intending to ask her to marry him, is high-hatted by her and, on being told by her about the marriage-to-be, sneers at her as just another phoney after money, and exits permanently, as he thinks.

Enraged, she returns to the former mansion, memorably smashes up pictures, mirrors, etc, in his bedroom (which used to be hers), is fiercely kissed by him (struggling, struggling) when he interprets the vandalism as repressed love declaring itself, and, when rival gangsters raid the club downstairs and Raft becomes the man of criminal action handing out the guns to his own guys, yieldingly acknowledge that, yes, she does too love him. The End.

Crime pays.

Dartmoor prisoners riot against inedible food, brutality by the guards and the punitive restrictions of a narrow-minded new Governor undoing the mild principled relaxings of three predecessors. For a few hours, the inmates have the run of the place, but are not violent. Later, there are savage beatings by the guards. A one-man official report whitewashes the administration.

Sir Oswald Mosley (the title inherited, not given) creates the British Union of Fascists (B.U.F.) after a dozen years of frustration in and out of Parliament and government, “and acquired almost automatically the encouragement of Britain's then biggest newspaper, the Daily Mail, which was more than willing to extend its admiration for the Italian original to the local imitation,” (David Low, Autobiography, 1956)

Bernard Shaw, addressing a meeting of the “gradualist” Fabian Society that he himself had co-founded in 1884 with Sydney and Beatrice Webb, says:

"You will hear more of Sir Oswald Mosley before you are very much older. I know you dislike him, because he looks like a man who has some physical courage and is going to do something, and that is a terrible thing. You instinctively hate him, because you do not know where he will land you. Instead of talking 'round and 'round political subjects, and obscuring them with bunk verbiage without even touching them and without understanding them ... he keeps hard flown to the actual situation."

Quoted in Robert Row, “Sir Osweld Mosley: Briton, Fascist, European,” Journal of Historical Review. This online article, from an extreme right-wing American publication, is interesting on how Mosley appeared to a number of intelligent and reputable thinkers in Britain in the Twenties and early Thirties.The baby son of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh is kidnapped and murdered, despite the ransom money having been paid, leading to the trial of Bruno Hauptman three years later.

In the worker’s paradise of the USSR, the government-created Ukraine famine begins, which by 1934 will have taken over five million lives, and been unreported in major Western papers.

This is the midnight—let no star

Deceive us—dawn is very far.

This is the tempest long foretold—

Slow to make head but sure to hold. …

1933

Leslie Charteris, The Saint and Mr.Teal

Just a Saint book (three long-short stories), irresistible in adolescence, and displaying the advantages of concision in a basically comedic mode. I include it here for the following passage, drawn to my attention by Benoit Tadié in his admirable article on British ways of coping in fiction with American criminality in the Twenties and Thirties:

He settled back in his corner and pulled at the brim of his hat—a broad-shouldered, prematurely old young man of about twenty-eight, with a square jaw and two deep creases running down from his nose and past the corners of his tin mouth. He was one of the first examples of a type of crook that was still new and strange to England, a type that founded itself on the American hoodlum, educated in movie theatres and polished on the raw underworld fiction imported by F.W. Woolworth—a type that was breaking into the placid and gentlemanly paths of old-world crime as surely and ruthlessly as Fate. In a few years more his type was no longer to seem strange and foreign, but in those days he was an innovation, respected and feared by his satellites. He had learned to imitate the Transatlantic callousness and pugnacity so well that he was no longer conscious of playing a part. He had the bullying swagger, the taste for ostentatious clothes, the desire for power, and he said “Oh, yeah?” with exactly the right shade of contempt and belligerence. (Part Two, ch. 1)

Incidentally, where did the stylistic tic of good-guy characters smiling “sleepily” and “dreamily” come from? Sam Spade does it at one point before knocking out Joel Cairo. The Saint does it passim. Paul Cain’s Kells does it. What does it look like?

Martin Porlock (Philip MacDonald), X vs. Rex (in the States, The Mystery of the Dead Police)

A curious anarchic work. Someone is killing inoffensive coppers on their beats, usually, if I remember correctly, with a knife. No private detective comes to the rescue. It’s simply police work trying to hunt down a serial killer who makes only a brief appearance at the end.

George Dilnot, Killer’s Castle, in The Thriller, no. 211, vol 8, February 18.

Another Thriller novel with “American” elements. See Note 45.

George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London

Opens (virtually) with a three-page white-slavery rape-and-abuse episode in an all-red underground room in a clandestine Paris brothel: The narrator is one of Orwell’s fellow plongeurs (dish-washers). The episode has nothing to do with the rest of the book, but I don’t imagine it hurt sales.

“More and more savagely I renewed the attack. Again and again the girl tried to escape; she cried out for mercy anew, but I laughed at her …

“Ah, how she screamed, with what bitter cries of agony. But there was no one to hear them; down there under the streets of Paris we were as secure as at the heart of a pyramid.”

Paul Cain, Fast One

A Hammettesque urban novel (cf. The Glass Key) that is so packed with abrasive action, has such a complicated plot, moves so fast, with so little description of settings and the ongoing looks of characters, and contains so little in the way of characters with whose aims one can empathize (Gerry Kells is no Ned Beaumont) that it is likely to be hard for the ordinary pleasure-seeking reader to get through it. It defeated me, anyway. The rigorously adhered-to technique, taken over from The Glass Key and The Maltese Falcon, of never describing internally what a character “thought” or “felt” didn’t help for me.

But obviously it’s all deliberate, an impatient paring away, in the interests of speed and puzzlement, of the elements that enabled Hammett, in the books I’ve just named, to move in a more leisurely fashion. It would obviously have been be studied by other writers. The short stories in Cain’s Seven Slayers are less experimental.

For a much more favourable appraiusal, see Paul Cain, Fast One in Supplementary.

John Spivak, Georgia Nigger

A powerful and socially influential novel, by a Georgian with official access to prison records, about the workings of de facto economic slavery for Georgia Blacks and the horrors of the chain gang. Centered around a young Black and his family, it has an experiential texture that I Am a Fugitive lacks, and no happy ending. According to a prefatory note in Glinto’s Deep South Slave, it was the inspiration for the latter.

See Sidebar 4

Ernest Hemingway, “A Way You’ll Never Be.”

Nick Adams recalls coming upon the dead after an attack in the Italian campaign

There were mass prayer books, group postcards showing the machine-gun unit standing in ranked and ruddy cheerfulness as in a football picture for a college annual; now they were humped and swollen in the grass; propaganda postcards showing a soldier in Austrian uniform bending a woman backward over a bed; the figures were impressionistically drawn; very attractively depicted and had nothing in common with actual rape in which the woman’s skirts are pulled over her head to smother her, one comrade sometimes sitting on the head. There were many of these inciting cards which had evidently been issued just before the offensive.

Paul Cain, “Murder in Blue,” Black Mask

Opens with three finely described and seemingly unrelated murder incidents in four pages. Out-of-work stunt-man Doolin figures out that they were all witnesses to a gangland shoot-out and gets himself taken on as a bodyguard by rich suck Halloran who, as Doolin figures, will be next on the list, at risk from young hit-man Martinelli. Doolin gets the facts of the situation wrong.

Martinelli, some way, made a high piercing sound in his throat as the knife went into him. And again as Halloran withdrew the knife, pressed it in again slowly. Halloran did not stab mercifully on the left side, but on the right puncturing the lung again and again, slowly.

The World Committee for the Victims of German Fascism, The Brown Book of the Hitler Terror and the Burning of the Reichstag

A richly-detailed 350-page documenting, by means of summaries, newspaper reports, lists, statistics, official statements, personal testimonies, and reported cases, of the Nazi machine of intimidation at work in politics, education, the arts, medicine, etc. The Nazi rhetoric is out-front odious, the lying barefaced, the cruelty frightful, with power flowing ultimately from the S.A. man’s rubber truncheon.

See Sidebar 13.

Arthur F. Raper, The Tragedy of Lynching

“[An] exhaustive and objective survey made by Dr. Raper and the Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching. For two years, the author and members of the commission visited the scene of every lynching that took place in 1930 and early 1931, assembled statements and opinion from witnesses, public figures, newspapermen, religious figures, and law enforcement officers” (Abebooks description)

H.G. Wells, The Shape of Things to Come

A hateful book, miasmic with the self-congratulatory irony that comes when, as in other books of pseudo-history like Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward and B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two, an imaginary writer is looking back from a distant and better future at the muddles of the past.

“History,” the story of the conflicts of nation states, is all a silliness, too often a homicidal silliness, occasionally illumined for an instant when someone glimpses the need the end of wars and nationalisms, and their superseding by a World State governed by a benign dictatorship of dispassionate scientists and social engineers.

Wells loves Lenin, likes Mussolini and Stalin, and despises Hitler as a ranting, clownish nobody. England stays out of the Second World War, which begins (in 1940!) with an attack by militaristic Poland on Germany, including a gas air-raid on Berlin.

A book serving to weaken the will of the democracies (which he despises) to resist the take-overs of Hitler, whom he doesn’t understand, in the rest of the Thirties.

This is the year in which, in the most prestigious debating society in the world, the Oxford Union, the motion that "This House will under no circumstances fight for King and Country" passes by 275 votes to 153.”

The Story of Temple Drake, Stephen Roberts.

A now unavailable (but in DVD process?) filming of Sanctuary with Jack LaRue and Miriam Hopkins that had many censorship problems.

Thomas Doherty provides a detailed description of the plot in Pre-Code Hollywood; Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934 (1999), pp.114-118. There is more about it in Mark A. Viera’s Sin in Soft Focus; Pre-Cody Hollywood (1999)

King Kong, Ernest B. Schoedsack and Merian C. Cooper.

From an idea by Edgar Wallace. Brute power eroticized. A helpless maiden (literally, probably) screams her powerless way deeper and deeper into the terrifying unknown. Subsequently Kong bites individuals in half, snatches a woman from her high-rise bedroom and drops her screaming to her death, and devastates a trainload of commuters. The ”primitive” isn’t just picturesque costumes and superstition, to be mined for “civilised” entertainments.

Norman Angell is given the Nobel Peace Prize, and brings out a revised edition of his principal work, The Great Illusion (1910), arguing for the futility of war as a way of making economic gains and settling international disputes.

Unfortunately his argument, except perhaps for the part against 1919-type punishments for making war, has not made its way into the hearts and minds of Germany’s new government. Insofar as it is the democracies whose will towards combat is weakened (the devoutly pacifist Neville Chamberlain believed that Germany had indeed had a raw deal), it contributes to the delay in halting Germany’s militaristic expansion and hence to the multimillions of deaths in the war that began in 1939.

In a widely noticed debate in the Oxford Union, the clever young gentlemen and future leaders, in their white ties and tails, pass by 275 to 153 the motion that “This House will under no circumstances fight for King and Country.”

The Volstead Act is repealed, ending Prohibition.

John Dillinger finishes an 8 1/2 year prison sentence in May, and the flamboyant bank-robbing career of his several-person gang, including Baby Face Nelson, commences.

Murder Incorporated, a largely Jewish group, is started up around this time by Albert Anastasia and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, and reportedly may have been responsible for five hundred contracted-for “disciplinary” mob killings.

In January Adolf Hitler, head of the National Socialist Party, is appointed Chancellor of Germany. After a General Election he is granted dictatorial powers by an intimidated Reichstag. By the summer there are forty-five concentration camps, ranging in size from a hundred to five thousand prisoners.

By the end of the year, over 100,000 political prisoners, predominantly Communists and Social Democrats, have experienced punishment (as distinct from extermination) concentration camps in Germany.

The most famous of these, before Auschwitz, is Dachau, established in March outside the market-town of Dachau, a few miles northwest of Munich and not far from the Alps. By the end of December, over 4000 prisoners have reportedly passed through its gates. (See Note 6.) Earlier in the year, the 2000-prisoner camp at Heub was the showcase camp.

The Dachau camp is almost 1900 feet above sea level. A former inmate recalls that “the winter is very severe. Snow often fell heavily from the end of November until April,” and that “The SS would not tolerate snow within the limits of the camp. If the flakes fell during the day, they had to be removed immediately from all places and streets.” (For more about the Nazis, see Note 6.)

Germany withdraws from the League of Nations.

And now no path on which we move

But shows already traces of

Intentions not our own,

Thoroughly able to achieve

What our excitement could conceive

But our hands left alone.

For what by nature and by training

We loved, has little strength remaining:

Though we would gladly give

The Oxford colleges, Big Ben

And all the birds on Wicken Fen,

It has no wish to live.

Soon through the dykes of our content

The gathering flood will force a rent,

And, taller than a tree,

Hold sudden death before our eyes

Whose river-dreams long hid the size

And vigours of the sea. …

Dime Mystery pulp magazine re-tools for horror and sex.

1934

James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice

Noteworthy for a first-person narrator—drifter, petty criminal— without any pretensions to virtue, not even the “guy” kind. Impossible to quote briefly, since the prose consists of more or less simple (but not Hemingway-mannered) statements that together build up a relatively complex picture of the thought-processes, often unverbalized or barely verbalized, of a couple of self-centered and rather superstitious working-class individuals fumbling their way towards murder.

Apart from the unwanted, amiably slobbish husband being struck on the head a couple of times and killed in a fake car accident, there are no what would conventionally be called violences.

B. Traven, The Death Ship; the Story of an American Sailor (Das Totenschiff in German, 1926.

Marvellous irreverent intransigent sardonic horrifying funny tragic kinetic buoyant poetic novel, the first-person account by an American sailor of what happens after he’s stranded in post-war Antwerp without papers and hence without (for bureaucrats) identity—funny-frustrating in the first part as he’s shunted back and forth across frontiers, coping dead-pan with cops, trying to talk American officials into helping him, doing a painless stint in jail, the archetypal Wobblyesque figure refusing to be awed by the State.

“And you came on the George Washington?

“Yes, sir.”

“A rather mysterious ship, your George Washington. As far as I know, the George Washington has never yet come to Rotterdam.”

“That’s not my fault, officer. I am not responsible for the ship.” (Part 1, ch.7)

In the second and longest part, gears shift as he experiences life aboard the only ship that will take him without papers, the battered, rusty, gun-running tramp-steamer the Yorikke. Working conditions in the stokehold are atrocious and at times literally lethal. (Stokehold Kurt, frightfully scalded while performing a heroic task, “screamed himself to death.”) But this isn’t simply “protest” writing. The outlaw Yorikke has a kind of grandeur as an emblem of universal exploitation, and the crew members, surviving once they’ve adapted, are emphatically not seen through Marxist-Leninist lenses. But it is a very powerful voicing from the under-class, and, much translated, it sells in the millions.

The editor at Knopf who handled Traven’s first two manuscripts, the other being for The Treasure of the Sierra Madr recalled them years later as being, stylistically, not by a native American. But he kept editorial revisions and suggests to a minimum, he said, and had Traven’s approval.

Who was Traven originally, before he came to the Americas? To judge from the Web, the jury is still out and may never return. But the Traven of the novels, whoever he was, is to love, and a reminder that noir pessimism and bleakness, and Marxist-Leninism, were not the only intellectually valid ways of coping. I’m surprised that the Surrealists seem never to have mentioned him.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night (translation by John H.P.Marks of Voyage au bout de la Nuit, 1932)

“When it was published in 1932, this then-shocking and revolutionary first fiction redefined the art of the novel with its black humor, its nihilism, and its irreverent, explosive writing style, and made Louis-Ferdinand Céline one of France's--and literature's--most important 20th-Century writers. The picaresque adventures of Bardamu, the sarcastic and brilliant antihero of Journey to the End of the Night move from the battlefields of World War I (complete with buffoonish officers and cowardly soldiers), to French West Africa, the United States, and back to France in a style of prose that's lyrical, hallucinatory, and hilariously scathing toward nearly everybody and everything. Yet, beneath it all one can detect a gentle core of idealism.” (Description on the Web.)

Werfel, Franz, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (trans)

Werfel’s great historical novel (Tolstoyan, Dostoevskian) about the heroic resistance of Armenian villagers to the attempted deportation by the Turkish army in 1915. Some obvious analogies with the Nazis treatment of the Jews.

In 1946, Q.D. Leavis says:

In Franz Werfel’s The Forty Days of Musa Dagh—surely one of the great novels of the world—we see … the slow building-up of sympathy with a nucleus of characters and of appreciation of the alien culture of which they are specimens. Werfel, a Viennese Jew, cannot have known the Armenian history from inside, but though we may suspect that the persecution of the Armenian race by the Young Turks nationalist movement and their resistance to assimilation was for him a symbol of the tragedy that was to take place in Europe (he wrote it in 1932), yet that history is completely realized from within, and the beauty and value of that extraordinary ancient culture is conveyed by a wealth of convincing detail … (Scrutiny, XIV, p. 138)

W. Reinhard, Nell in Bridewell (translation of Lenchen im Zuchthaus, ca. 1848), Fortune Press, first publication in England.

A novel about—and emphatically against—flogging in German women’s prisons, bringing out convincingly the non-pleasurable suffering of the beaten body. Traces of the book are discernible in Kafka’s ”In the Penal Colony.” R.A. Caton’s Fortune Press was a one-man fringe operation that combined curiosa with giving a number of young writers, especially poets, their first break in print, Philip Larkin among them.

Geoffrey Gorer, The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade.

A disquietingly sympathetic presentation of disquieting ideas.

Wilhelm Stekel, Sadism and Masochism; the Psychology of Hatred and Cruelty.

First authorized English edition.

Henry Champly, The Road to Shanghai, trans.Warre B. Wells.

A lightweight book by, as he explains, a friend and admirer of Albert Londres, who died in a freak accident at sea. Promises far more titillation than it provides. A narrative of how he travels from Marseilles to Shanghai by ship (he doesn’t arrive till p. 157), trying to test the reports he’s heard that white women, especially French women, are now greatly in demand in China, and ascertain how they get there, and whether it’s by force or voluntarily.

Lots of “verbatim” conversations, chiefly with traffickers, madams, pimps, colonial administrators. No sensuousness. Apparently the white women go out there voluntarily, for the money.. A touch of horror in six-page chapter XVII, short on details, about current child-slavery in British Hong Kong, tacitly ignored by the administration. Seven pages about a visit to a swarming red-light district in Shanghai.

“What?” I asked Natacha, who was pulling me along. “Really White women here, in Foochow Road, at this time of night?”

“Here?” she retorted fiercely. “Anything you like. Do you want children? Do you want monstrosities? You can have them by the ship-load. Do you want opium? Just smell—every second house is an opium den.” (p.192)

I think I read that the book sold well.

H.C. Engelbrecht and F.C. Hanighen, Merchants of Death: a Study of the International Armament Industry

A compelling in-depth analysis of the growth and operations of the international armaments industry, with its trans-national conglomerates, its links with governments, its master-agents like mystery man Sir Basil Zaharoff, its vast sales., its resistance to talk about disarmament.

The authors conclude that:

The arms industry is plainly a perfectly natural product of our present civilization. More than that, it is an essential element in the chaos and anarchy which characterize our international politics. To eliminate it requires the creation of a world which can get along without war by settling its differences and disputes by peaceful means. And that involves remaking our entire civilization. …

The skies are again overcast with lowering war clouds and the Four Horsemen are again getting ready to ride, leaving destruction, suffering and death in their path. … (Ch. 18)

Triumph of the Will, Leni Riefenstahl.

Irresistible-seeming energy and solidarity of the New Germany, with an effective vulgarization of the images of heroic workers in the Russian silents. A movie assignment from Hell—make a British Triumph of the Will featuring then Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald!

Viva Villa!, Jack Conway.

The savagery of revolutionary Mexico effectively conveyed with a pre-Code freedom in places, though obviously there were cuts. Wallace Beery excellent as Villa.

The Man Who Knew Too Much, Alfred Hitchcock.

A wincingly perfect encapsulation of some English class patterns, continuing those of the Great War—the ideal good-sports, service-middle-class nuclear family (cheerful, undaunted Leslie Banks), the stiffer upper-echelon cops doing the social controlling, the NCO-type bobbies marching instantly towards the besieged house when told to and getting shot down for their pains. Plus “political” foreigners who use guns and aren’t sportsmen.

Based on the 1911 Siege of Sidney Street, East London, in which two members of the Gardstein Gang (Latvian anarchist burglars) armed with Mauser automatics hold off under-armed police, supplemented by Scots Guards marksmen until they are killed.

A series of skillfully executed and very profitable smash-and-grab raids begins in December in London and the Home Counties, organized by Billy Hill, just out of Wandsworth, and principally hitting jewelers and furriers.

At a mass meeting of the British Union of Fascists in the Olympia arena in London, hecklers are violently evicted by Mosley’s paramilitary “blackshirts.”

The Peace Pledge Union is founded in Britain, its members pledging, “I renounce war and I will never sanction another.” Among them are Bertrand Russell and Aldous Huxley.

Joseph I. Breen takes over as the enforcer of the 1930 Production Code, puts teeth in it, and launches Hollywood on six “golden” years of cleaned-up entertainment, with costumes dry-cleaned each day, smoother faces, honest officials, and decent poor folks.

Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, archetypal doomed lovers who came together in 1930, are shot to death near Gibland, Louisiana by Texas and Louisiana peace officers, ending the Barrow gang’s 1932-34 crime spree.

Public Enemy Number One, John Dillinger, is shot to death by FBI agents outside the Biograph movie theatre in Chicago.

In the Night of the Long Knives (Nacht der langen Messer), in order to allay the anxieties of Hitler’s financial backers and the German High Command, Himmler’s SS wipes out the leadership of the S.A. (Storm-Troopers, Brownshirts), the Communist-fighting thugs under the command of Hitler’s principal rival and former comrade-in-arms, the socially more radical Ernst Röhm. The London Times covers the event “as if it were a perfectly legitimate political act—a ‘genuine’ effort to transform revolutionary fervour into moderate and constructive effort and to impose a high standard on National Socialist officials.” (Ferguson p.340)

Terror Tales pulp magazine comes on the market.

Civilization is hooped together, brought

Under a rule, under the semblance of peace

By manifold illusion; but man’s life is thought,

And he, despite his terror, cannot cease

Ravening through century after century,

Ravening, raging, and uprooting that he may come

Into the desolation of reality:

Egypt and Greece, good-bye, and good-bye, Rome!

1935

Grierson Dickson, Soho Racket

American gang leader in London (with aspiration to acquire manners of English clubman); tough Irish-American cop hoping to nail him; languid-seeming Scotland Yard cop (affectionate nickname “Cissie”); cruel German gangster; young English weakling; two or three decent girls; robberies; a bit of (unofficial) Third Degreeing by American cop; gunfire; hand-grenades. No disturbing details; no credible-sounding criminal speech; no feeling of Soho, apart from an Italian restaurant. Paperbacked by The Crime-Book Society in “a great new series of ‘Thrillers’ and Detective Stories,” along with Hugh Clevely’s The Gang-Smasher, Edgar Wallace’s On the Spot, and titles by Bruce Graeme, Sydney Horler, Seldon Truss, Andrew Soutar, Paul McGuire (back cover).

James Mackinley Armstrong, as told to William J. Elliott, Legion of Hell, London, Sampson Low, Marston.

A deglamorizing account of service in Morocco in the early 1920s in a French Foreign Legion characterized by criminal indifference to the welfare of its common soldiers and punishments worse than those that were being reported in the Thirties from Nazi Germany. At one point the narrator says of a prison camp,

I have described some of the tortures inflicted in this hell-hole upon soldiers of France for mere disciplinary offences. But the tortures inflicted upon the Riffs, in order to get information out of them, and so on, I cannot describe. They are indescribable (p.204).

So much for the ”civilization” that France was fighting to maintain in its North African colonies.

Jonathan Latimer, Headed for a Hearse

Echoes of Latimer can be heard in at least three of James Hadley Chase’s early novels. But the episode from which the passage below comes is unique, in my experience.

Butch picked up the chromium squeezer. It had two long handles which gave leverage to crush the lemons. … The center of the squeezer fitted nicely in the soft palm pf the Italian’s hand. “That’s tender, ain’t it, Dago?’ Butch inquired. He pressed the ends of the squeezer toward each other.

Petro’s hoarse screaming was loud in their ears. (Ch. XI)

These lines would be excised, along with a number of others, by the editors of the Dell Great Mysteries edition, 1952.

B. Traven, Government; first English-language edition of Regierung (1931)

Fictional analysis of the workings of the technically legal (and hypocritical) system whereby Mexican peasants are secured as virtual slave labour for concentration-camp-like plantations around 1909 in Porfiro Diaz’s Mexico.

Dennis Wheatley, ed., A Century of Horror Stories.

Plenty of flesh-creeping here, but the most terrifying anthology in my own childhood experience was Switch On the Light, which included H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Rats in the Walls.”

Spicy Mystery, August issue (2004 Wildside Press reprint)

The first thing that grabs your eyes after the ads is a large swastika on the left side of the two-page drawing of a top-hatted, masked, evening-dressed figure swinging a large axe which will descend on the neck of a kneeling blonde with her head on an execution block. The consciousness of the American protagonist of Robert Leslie Bellem’s “The Executioner” shifts after an accident into that of his twin brother, a headsman for the Nazis and, after a brief meeting with the Fuhrer, he executes unwittingly the lovely blonde with whom he has fallen in love.

Dime Mystery, January 1935

In Mindret Lord’s “Hostage to Pain,” a sadist with financial motives, assisted by two Germans wanted in Germany for murder, prepares to do some torturing to death.

Beth was dragged up to this horrible contrivance. Then, while Hans and George held her arms, Nevin put his hands inside the neck of her dress and ripped it down the front. In a second, her clothes were lying on the floor in tatters and she was as naked as the day she was born.

With my right leg dangling uselessly, I was pulled along the floor. My feeble struggles did not help. They tied me to a post only a few feet from the rack in which lay the youthfully molded, beautifully curving body of the girl I loved. Constant shudders ran through her stretched muscles. I could see her heart pounding in her breast.

The hero manages to kill one of the Germans, and rescue comes in the nick of time. But potentials, at least in “exploitation” genres, escalate into actualities. The unthinkable becomes thinkable and then do-able, and soon there will be stories in which help does not arrive in time.

The publishers of Warren Smith’s admirable novel Bessie Cotter, about the lives of prostitutes in a Chicago whorehouse, Messrs. William Heinemann, are fined a hundred pounds (the equivalent of at least four thousand now), with a hundred guineas costs, at the Bow Street magistrate’s court,